WhatsApp enables monitoring of attacks on health care workers in Syria

9 June 2017 London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine https://lshtm.ac.uk/themes/custom/lshtm/images/lshtm-logo-black.png

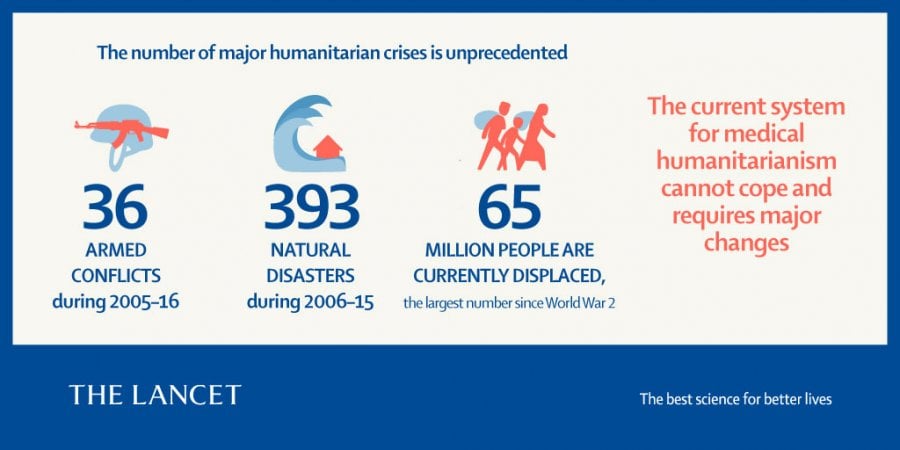

Health in Humanitarian Crises Series infographic. Credit: The Lancet

The messaging service WhatsApp is being used in Syria to help monitor and collect data on attacks on health care workers and facilities. This is providing important evidence to help support efforts to hold perpetrators to account, according to a new study published in The Lancet. The study is part of a wider Lancet series led by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, which calls for improved evidence and reform of the humanitarian health system.

The WhatsApp tool, which enables teams to share data about attacks within 24 hours, identified 402 attacks against health care in Syria between November 2015 and December 2016. The findings show that during the year of the study, nearly half of hospitals in non-government controlled areas were attacked and a third of services were hit more than once.

Attacks on health care have reached unprecedented levels in Syria, now in its seventh year of conflict. Collecting robust and reliable data is important to convince the international community to enforce legal protections, and to achieve accountability for widespread breaches of international law.

While reporting of attacks has improved, until now there has been no standardised method of collecting robust data. Collecting first-hand accounts from people on the ground can result in limited coverage, and using second-hand data such as media reports, satellite images and retrospective accounts can result in incomplete data, and collection is hampered by access constraints, security fears and concerns about confidentiality.

Study co-author Hilary Bower, Research Fellow from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said: “Capturing, verifying and transforming eye witness accounts of attacks on health care facilities into robust, reliable data is essential if perpetrators are to be made accountable under international law. Without this, they will continue to undermine the credibility of witnesses and deny responsibility. The tool presented in this report will help health care workers and others in the most difficult circumstances to consolidate and present hard evidence to an international community that has so far failed to stop deliberate attacks on health care in many conflicts.”

Following the 2010 UN General Assembly Resolution that threats to health care should be addressed, the World Health Organization (WHO) was tasked to develop a method of collecting more reliable data on health care attacks.

The new tool was piloted by the Health Cluster in Gaziantep (Turkey), which coordinates humanitarian activities in Syria, including the UN and around 50 NGOs. The Health Cluster supports 352 health facilities in Syria, serving a population of approximately 5.5 million people.

The monitoring tool uses a 293-member WhatsApp group. When an incident occurs, a short message is posted to the group. All members with physically-verified information (ie, who have visited the site or were present – not hearsay) are then asked to complete an anonymous and confidential online form to detail location, attack type (eg. aerial bombardment, gunfire, arson), facility type, extent of damage, who was affected, injuries and deaths.

Within 24 hours, the team in Turkey issues a flash update to key partners, the WHO, UN and donors. Every month, data is verified by checking health cluster alerts against external reports. Reports that remain unverified because of insufficient information are also recorded.

From November 2015 to December 2016, 402 individual attacks were identified, of which 158 were verified. A total of 938 people were harmed, a quarter of whom were health workers. Services providing trauma care were attacked more than other services. Aerial bombardment was the main weapon, and land operations to take over a specific location were associated with increased attacks.

Dr Alaa Abou Zeid, Emergency Health Coordinator, WHO Health Cluster, Gaziantep (now Health Cluster Coordinator, WHO, Yemen) and lead author of the paper, says: “On a daily basis, we have witnessed the efforts that partners do to keep health facilities operational, including dividing facilities, such as operating theatres and post-operative care, among locations to try to reduce the risk that all services are affected, or moving entire services underground. Our challenge now is to convince our colleagues on the ground to continue collecting and verifying data, when they have still not seen a reduction in attacks. We urge the international community to mobilise and apply the Geneva Convention with conviction in order to effectively protect health care and similar civilian services in conflict.”

The wider Lancet Series, which was led by the School’s Professors Francesco Checchi and Bayard Roberts, assesses the evidence base for health interventions in humanitarian crises and finds there are critical gaps in knowledge and practice.

Large-scale humanitarian crises are ongoing in Syria, Afghanistan, Central African Republic, DR Congo, Iraq, Libya, Nigeria, Somalia, South Sudan, and Yemen among others.

Worldwide, an estimated 172 million people are affected by armed conflict, including 59 million people displaced - the highest number since World War Two. In addition to these man-made crises, 175 million people are affected by natural disasters each year.

The four-paper Series reveals significant variations in the quantity and quality of evidence for health interventions in humanitarian crises, and brings together lessons learned from recent failures in humanitarian crises to provide recommendations to improve a broken system. It calls for action to put the protection of humanitarian workers front and centre, to align humanitarian interventions with development programmes, to improve leadership and coordination, to ensure timely and robust health information, and to make interventions more efficient, effective and sustainable.

Francesco Checchi, Professor of Epidemiology and International Health, said: “Timely and robust public health information is essential to guide an effective response to crises, whether in armed conflicts or natural disasters. Yet insecurity, insufficient resources and skills for data collection and analysis, and absence of validated methods combine to hamper the quantity and quality of public health information available to humanitarian responders. Far greater investment and collaboration across academic and operational agencies is needed to generate reliable evidence, and improve the response to humanitarian crises.”

Publication:

Francescco Checchi, Bayard Roberts et al. Health in Humanitarian Crises, The Lancet. June 2017. (Series includes four main papers, four comments, one profile and the article on WhatsApp in Syria.)

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.