When Cosmas Bunywera went to school in the Kenyan Rift Valley more than 20 years ago, few children wore glasses, opticians were rare and most pupils’ eye problems were not picked up until it was too late.

The Rift Valley is remote, located 90km north of Nairobi and vision - or lack of it – wasn’t talked about, with a knock-on effect on education and learning.

While injuries to the eye and allergies play a role, it’s uncorrected refractive errors, such as far and near sight, and astigmatism, that are the most common cause of vision impairment worldwide.

Refractive errors are also the second most common cause of blindness, according to a World Health Organization (WHO) report. These conditions can be prevented early with glasses, but the issue is knowing who needs them.

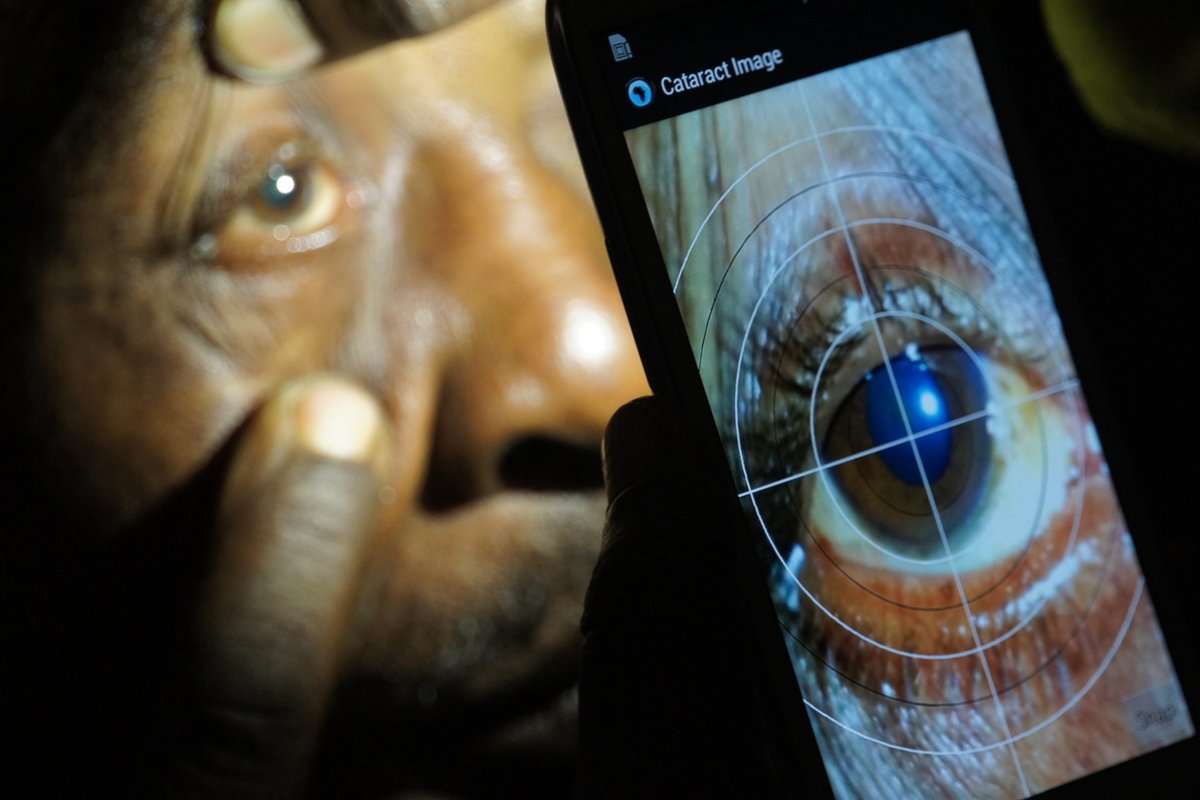

Now Cosmas, 28, is part of a huge eye health screening operation in his home country, known as Peek, where ordinary people – school leavers, teachers, health workers -- can test people’s sight and identify if further investigation is needed - with a swipe of a smartphone.

“Phones are having a big impact,” he says, smiling. “It gives me a lot of satisfaction that we can screen a lot of people for problems, who didn’t even know they had problems, and refer them to hospital to see a specialist and get attended to.”

Cosmas adds the programme is now screening in schools. “I’m so happy that children who would have lost vision from not being aware can be treated,” he said.

The operation used mobile phones to monitor a community’s health, known as mHealth - the use of mobile and wireless technologies to support the achievement of health objectives, according to the WHO.

Mobile domination

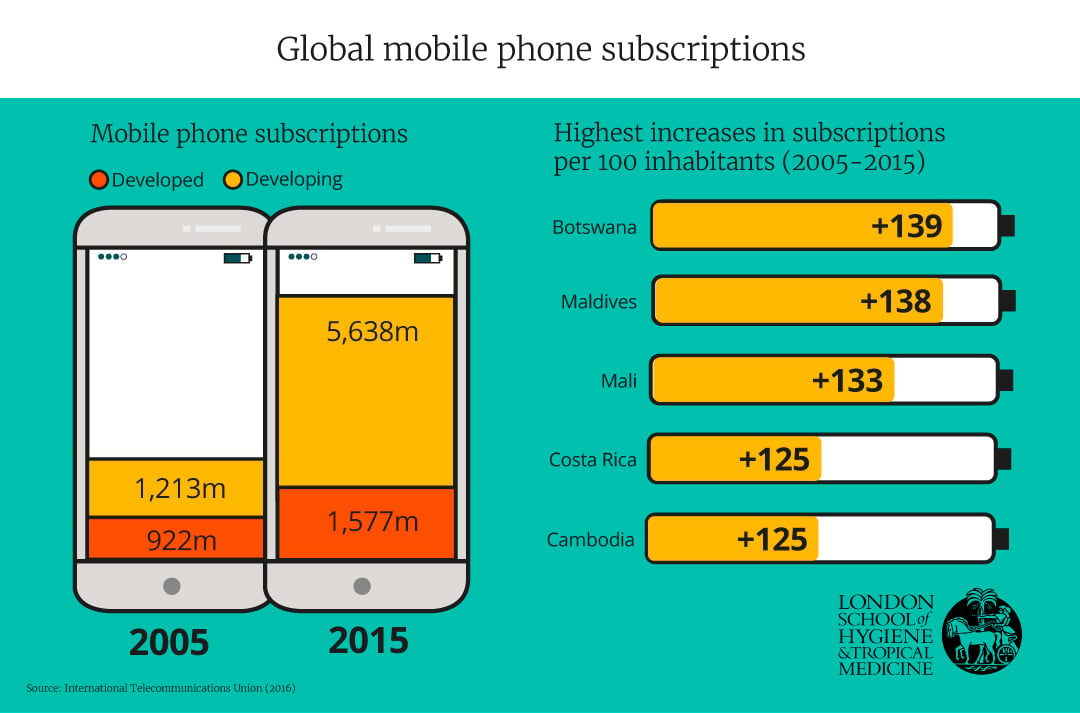

The success of mHealth as a whole has been fuelled by the astounding increase in mobile phone ownership by ordinary people, particularly in developing countries.

According to the International Telecommunications Union, in 2016 there were an estimated 7,377 million mobile phone subscriptions in the world, compared with 2,205 in 2005. Of those numbers in 2016, an estimated 5,777 million were in the developing world, compared with just 1,213 in developing countries in 2005.

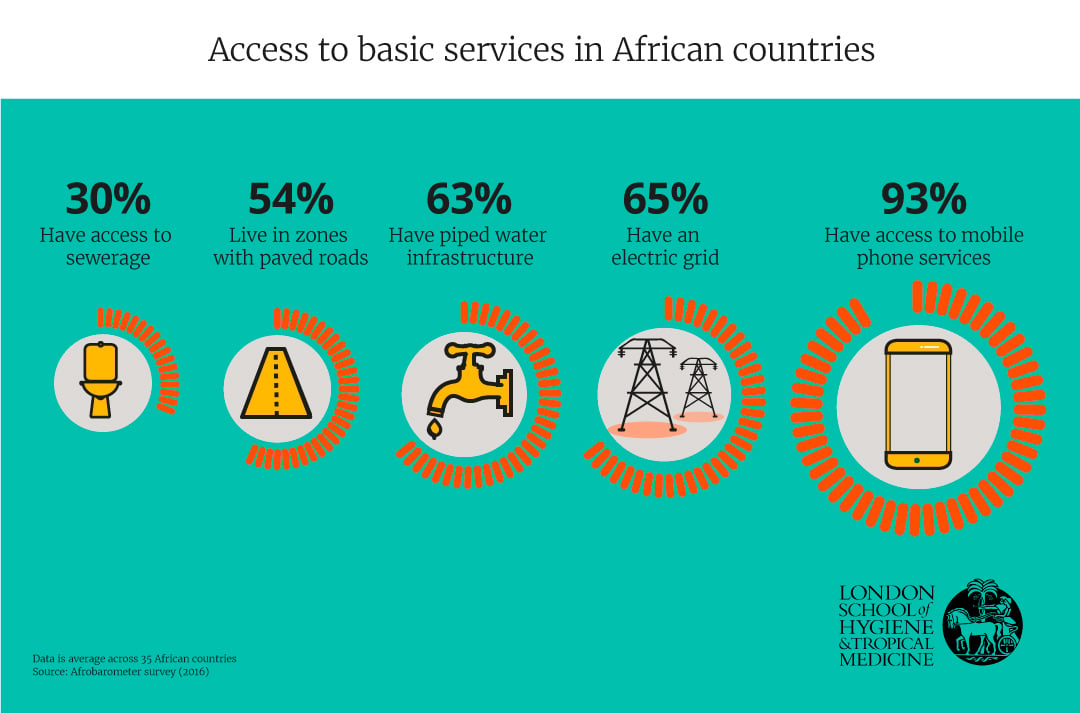

This equates to more Africans having access to mobile phone services (93%) than piped water (63%), according to a 2016 report by Afrobarometer – and the trend is predicted to increase. A Cisco report predicted that by 2021, more people will be using mobile phones (5.5 billion) than bank accounts (5.4 billion), running water (5.3 billion), or landlines (2.9 billion).

Dr Alain Labrique, Director of the Johns Hopkins University Global mHealth Initiative, believes the diversity of technology is “quite phenomenal.”

“What has made it so attractive is the universality of it, how easily this technology has spread throughout the global south, where most of these challenges are faced, but also in high and middle-income countries,” he said.

Cosmas is a great example of this expansion. He was a keen user of mobile technology and the first person in his family to get a basic mobile phone at the age of 21. Now all his five siblings have smartphones and use them to get health tips.

His use of smartphones in a professional capacity, however, goes much further.

Peeking into good eye health

Cosmas has visited hundreds of schools and rural communities using the Peek Acuity app and the Peek eye health system. He is working with Dr Andrew Bastawrous, Assistant Professor of International Eye Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and CEO/Co-Founder of Peek Vision, a social enterprise which aims to reduce barriers to services that can restore sight.

Cosmas first got involved when Dr Bastawrous, an ophthalmic surgeon-turned PhD student at the School, needed a technically-minded individual to help transport and maintain the equipment he was taking to 100 remote communities in Kenya.

At the time, Cosmas, then 23, was a freelance computer-repair man in Nakuru and he jumped at the chance to help local communities while pursuing his passion for tech. “I didn’t know anything about eye problems. If my family had any sight issues, I didn’t know back then.”

Dr Bastawrous was keen to show him different eye problems to help him learn, he said.

During his early research, Dr Bastawrous realised it would be impossible for everyone who needed to be tested to be seen by someone like him and with such high-tech equipment as there are too few specialists available. He decided to turn a smartphone into a mobile eye clinic instead, which anyone could use with some basic training.

Now technical lead for Peek’s work in Kenya, software developer Cosmas says his work gives him real purpose. “This technology is enticing, it’s so portable and easy to learn to use to identify people with poor sight, the impact is very satisfying, especially in children,” he said.

To test sight using the Peek Acuity app, a capital letter E is shown on the phone’s touch screen. It changes in orientation and size, with each size being a different vision level. The patient points in the direction of where the letter is facing – down, up, to the side - and the tester records this response by swiping the phone screen in response to the patient’s gestures. If the patient can’t tell which direction the letter is facing, the phone is shaken to indicate the letters weren’t visible to the test taker.

The app then automatically works out if the answer was right or wrong and calculates the vision score. It also depicts on the screen how the person sees the world with their eyesight and tells the user if a referral is required.

Since Peek first launched, more than 100,000 children in Kenya have been screened by teachers in schools, 5% of whom have been found to be seriously visually impaired and referred on for treatment. Community volunteers are also starting door to door testing to screen older people. This means specialists are freed up to work where they are most needed and better used - in hospitals.

The Peek system links patients all the way through from the service to the appropriate treatment centre and then tracks whether that treatment has worked.

The initial Peek trial explored whether a nurse or a non-medically trained school leaver using a mobile phone could provide the same referral decisions as the specialist using state of the art equipment. “We were able to demonstrate that they could,” said Dr Bastawrous.

As well as Kenya, Peek is being used in India and Botswana, and trials are active in Ethiopia and Tanzania. In Botswana, healthcare auxiliaries doing vaccinations have been trained to do the vision testing as well, and have screened 13,000 people, with plans now in place for this to be rolled out nationwide.

Population screening using mobile phones means public health teams can have a clear understanding of the epidemiology of a disease and be ready to respond when urgent treatment is needed.

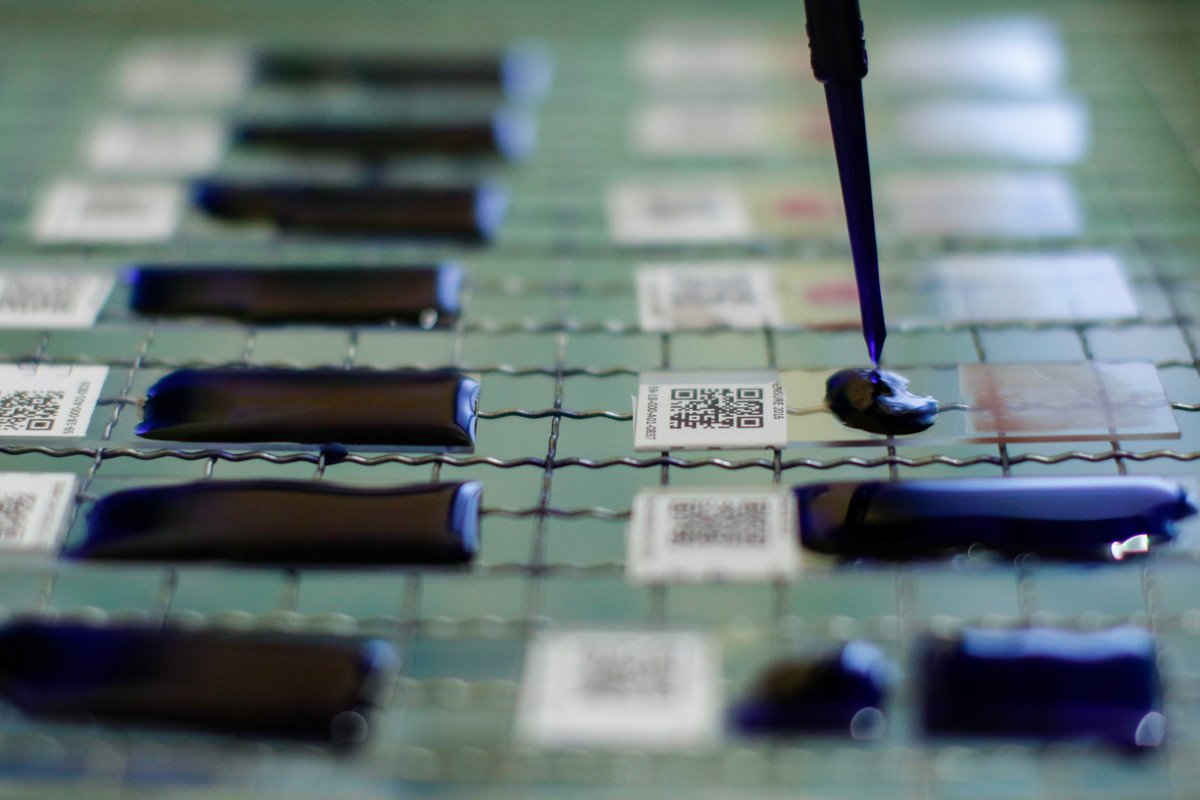

One further project in the Philippines by researchers at the School, known as ENSURE, is using computer tablet technology to track cases of malaria and combining this with insight from blood samples of those affected to create detailed maps of areas where transmission is occurring.

But other forms of mobile technology – this time in the sky – can enable monitoring on an even broader scale.

From phones to drones

Drones controlled via tablets are helping teams at the School investigate the rise and spread of malaria.

In Malaysian Borneo, Kimberly Fornace, Research Fellow in the School’s Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Diseases, is using two drones to map deforestation after a surge in human cases of ‘monkey malaria’, a strain of the disease that normally only affects macaques, caused by the parasite Plasmodium knowlesi. It’s believed clearing of trees is helping monkeys spread this to humans due to increased contact.

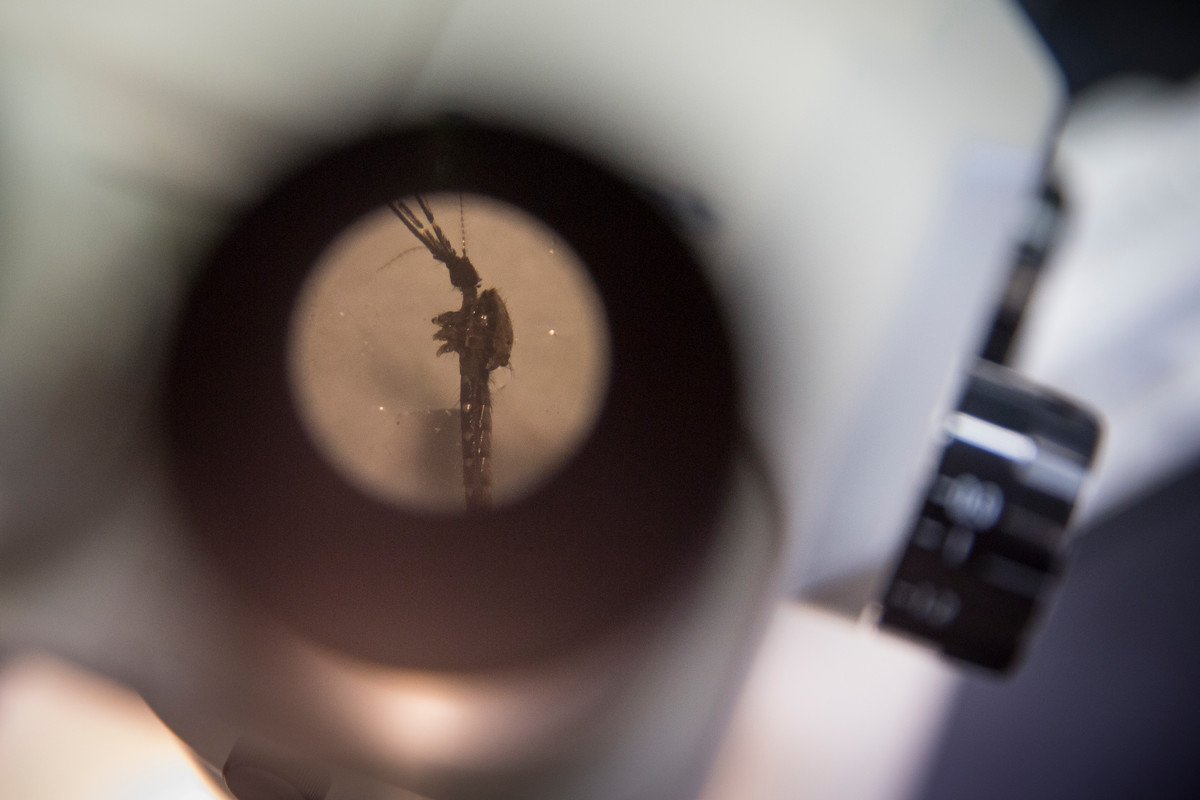

This form of the disease is commonly misdiagnosed as a mild form of malaria called P. malariae as it looks similar under the microscope. But the monkey form - now the most common type of malaria in the state of Sabah - is severe in humans and has a high case fatality rate, meaning a greater chance of dying if infected and hospitalised. This is because of the parasite’s rapid replication cycle.

In addition to having the highest case fatality rate, P. knowlesi has the highest proportion of severe disease, according to one study.

There are believed to have been between 700 and 1,000 cases of P. knowlesi in humans in Sabah, with five to six deaths each year. However, the death rate is now falling due to a new policy of unified treatment with an artesunate compound that is much better at treating monkey malaria in humans.

Interestingly, the parasite doesn’t appear to affect the monkeys. The majority of macaques in the area test positive for knowlesi and researchers suspect they have low-level asymptomatic infections.

Dr Fornace believes that as trees were cut down for agricultural development and timber sales there was more contact between monkeys and humans leading to the increase in human cases.

The team at the School are therefore using drones fitted with cameras to picture and map the changing forest landscape. Separately, they are tracking the monkeys’ movements through GPS collars placed on the animals to see how the macaques are moving in response to the forest clearing and if they are going closer to the houses and closer to the people.

While monitoring the forests with a £10,000 fixed wing drone, programmed and operated by a laptop, the team now also uses a helicopter drone with a thermal camera attached to find macaques in the forest using their heat signature. This helicopter drone is programmed from a tablet and was made in collaboration with the Sabah Wildlife Department in a project led by Chris Drakeley, Professor of Infection & Immunity at the School.

“Compared with satellite data when you look at the costs and the availability, it works out much, much cheaper,” said Dr Fornace.

Research so far has found that people in villages with significant deforestation around them were more likely to be infected with the P.knowlesi form of malaria.

In Northern Sabah, the LSHTM researchers found that villages where substantial areas of forest had been cleared in the past five years had 1.5 to three times higher incidence of this form of malaria reported.

The drone data also revealed that that deforestation altered the macaques’ movement patterns, in some cases causing them to move nearer to humans.

Dr Fornace and Prof Drakeley believe their drones – and the revelations that came from them – have had a positive effect. Public health officials from the Ministry of Health are now being more proactive about malaria prevention measures such as insecticide spraying and distribution of bed nets when tree clearing is going on, they said.

The next step, they say, is to develop risk maps to look at places that are more likely to get P. knowlesi, and predict where might be affected in the future to inform malaria control programmes.

But such high-level technology isn’t the only way mobile technology is being harnessed at the School. Even something as simple as an old Nokia is being used to help women stay free of STIs and use effective contraception after an abortion.

Handling sensitive issues – on a phone

In Cambodia, Assistant Professor and population health scientist at the School, Dr Chris Smith has had success providing sexual health information to women through the use of basic phones.

With his MOTIF trial (MObile Technology for Improved Family Planning), Dr Smith studied whether sending voice messages reminding women about the importance of continuing with contraception after an abortion and offering telephone counselling helped maintain its use.

Because literacy rates are low in this region and the Cambodian script could not be used on the basic phones that people used, texting would not have worked.

In earlier research, Dr Smith found that women were having unaffordably large families – often with six to seven children - but they often stopped using contraception.

There were many reasons they stopped, including side effects such as not menstruating, or local myths that claimed condoms caused cancer or the IUD coil can grow legs and walk around the body.

“Studies have found that in Cambodian culture, it’s particularly important for a woman to regularly menstruate, to get rid of what they call the ‘bad blood’ every month,” said Dr Smith, who is also a GP in the UK.

“We realised ongoing support for contraception users was needed to help with side effects … [and] almost everyone had a mobile phone.”

In his trial, Dr Smith recruited women who had sought an abortion from four Marie Stopes International clinics, two on the outskirts of the capital Phnom Penh, and two in the provincial towns of Battambang and Siem Reap, which serve rural populations.

Of the 500 women taking part, 249 received calls to their mobile which, when they answered, played a recorded message reminding them about contraception and the availability of support. They received six of these over three months. The remaining 251 women did not receive messages.

| Message one sent within a week of using abortion services |

|---|

| “Hello, this is a voice message from a Marie Stopes counsellor. I hope you are doing fine. Contraceptive methods are an effective and safe way to prevent an unplanned pregnancy. I am waiting to provide free and confidential contraceptive support to you. Press 1 if you would like me to call you back to discuss contraception. Press 2 if you are comfortable with using contraception and you do not need me to call you back this time. Press 3 if you would prefer not to receive any more messages.” |

A third of the women chose the option to speak to a counsellor and were given personalised information, encouragement and reassurance.

“We found that the counsellor was providing support for broader issues such as post-abortion care, and even emotional support to clients,” said Dr Smith. “Moving forward, we could improve the intervention by broadening its scope.”

In the group that did receive the messages, self-reported contraceptive use increased at four months, soon after receiving them, but at 12 months follow-up, the effect was not sustained. “It’s a good proof of concept that this sort of support can be effective,” he said.

In a follow-up study, the team interviewed 15 of the women who took part and most were positive and said the intervention gave them a convenient way to ask questions or get advice without going to a health centre.

The trial has not been formally scaled up but the clinics involved are now carrying out more follow-up phone calls with patients following an abortion.

As mobile phone technology has developed since the trial, Dr Smith believes instant messaging apps such as WhatsApp or other platforms, where the user can respond at their convenience, may make future schemes more effective.

Other researchers are tailoring studies based on the different types of phone a population uses.

For example, in Tajikistan and Bolivia, where smartphone use is more common, Dr Ona McCarthy, a Research Fellow in epidemiology at the School, has developed interventions to increase acceptability and use of contraception among young people. These use instant messaging delivered via a specially-developed app.

But for the same study, in Palestine, text messaging is her main option as the population mostly use basic phones.

But even in developed countries like the UK, simple text messaging is having positive impact.

Enabling intensive support by text

Dr Caroline Free, an Associate Professor in epidemiology and primary care at the School, ran a trial called txt2stop, which motivated smokers in the UK to quit and found that those who had the support of personalised texts over six months were twice as likely to succeed.

After the trial’s publication in The Lancet, she advised WHO on implementing a similar service in India, where there is a high burden of tobacco deaths. The service launched last year with two million people taking part and since then, a further 27 countries have expressed interest in organising similar services.

“Many of the effective behaviour change interventions are very intensive, and require people to commit to lots of time,” said Dr Free, highlighting that face-to-face smoking cessation support can entail going to see someone every week for several weeks for half an hour each time.

“Lots of people are looking for something that’s easier to access, and mobile phones are an exciting way of providing that.”

The increasing levels of phone ownership and extensive coverage geographically all over the world means that for the first time, support can be provided for those who need it wherever they are.

Dr Free, who is also a GP in south London, has now turned her attention to helping young people with STIs and to tell partners they have had a recent STI diagnosis. And she’s doing this using text messages.

When women go to the doctor after such a diagnosis to get antibiotics, she says they are often surprised and upset. It is not always an appropriate time to start a discussion about ongoing safer sex and how to tell a partner about the infection. Texting them later on could therefore be a way to restart communication.

She is currently recruiting 5,000 men and women aged 16-24 with a recent chlamydia or gonorrhea diagnosis across the UK for a study testing the impact of receiving frequent text messages with information and tips on sexual.

“Texting patients about safer sex, would give me the opportunity to reinforce what I would otherwise like to cover during a consultation,” said Dr Free.

During focus groups in south-east London and Cambridgeshire before the trial started, women said they found telling a partner about their diagnosis very difficult.

To date, not many mhealth interventions on notifying partners have proven to be feasible, or effective, but the team at the School plan to change that.

“This is a new approach, in that it’s gently supportive of telling a partner. It’s enabling, not just telling you what to do and showing you how you might do that,” said Dr Free.

Dr Free hopes to take a seemingly challenging task and make people realise it’s “not such an impossible thing to do, after all”.

Is technology the key to future public health?

While this sea of available technologies has enabled research teams at the School to enter previously unchartered territory in terms of behaviour change, disease surveillance, diagnosis and care, most of them know the caveats they must keep in mind.

“mHealth has endless possibilities with multiple diseases. But we don’t want to overburden health systems with too much information (and server space),” said Prof Drakeley. “We need a sweet spot between masses of terabytes and the minimal essential data that is needed to act and operate effectively.”

Dr Bastawrous agrees it is important for these technologies to be used in an appropriate way, solving a genuine need.

“The potential for mHealth is the same for paper health in that if data is recorded well and is used in the best interest of beneficiaries, its value is huge,” he said

But he adds that mhealth has the potential to amplify any negatives in the system, such as referral services. “If we find lots of people who can’t see and there is no service for them, we are creating a huge problem. That’s why we are committed to holistic solutions that ensure demand for services can be realised.”

Dr Labrique believes that machine learning and artificial intelligence should help with any data interpretation issues, but accepts that strengthening services is vital.

“No matter how good your digital health system is, if your patient needs to be taken by ambulance for a C-section there’s not an app that is going to do that,” he said.

He sees digital health as a part of an ‘eco-system of solutions,’ and argues that just because something doesn’t solve every problem, it should not be dismissed. “It’s giving us the ability to recognise problems, to engage people and bring them to services,” he says.

We hope you enjoyed reading about our work in this feature. If you are interested in supporting projects like these and the many others we are leading to improve health worldwide, we would be delighted to hear from you. There are many ways you can make a gift to the School, from wherever you are in the world. Each and every gift we receive makes an impact, from funding scholarships, to updating our facilities or investing in new avenues of research. Whether it’s a gift of £5 or £500,000 your generosity will support our mission to improve health in the UK and around the world.