This feature is available for republication under a Creative Commons licence.

When Dixon Chibanda was a medical student in the Czech Republic, one of his friends took his own life by suicide. It was the first time Chibanda recognised mental health as something that affected people in his home country. He wasn’t considering a career in psychiatry – his preference was originally paediatrics or dermatology – but he fell in love with it during his training rotation in mental health.

Chibanda returned to Zimbabwe and became a student of Dr Vikram Patel– a leading global mental health researcher and honorary professor at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) – while Patel was teaching psychiatry at Harare Central Hospital in the early 1990s. After graduation, all but one student – Chibanda – left Zimbabwe for other wealthier countries.

“Initially my interest was to practice psychiatry in a huge psychiatry hospital and make a difference in the lives of people who are affected by different mental health issues,” Dr Chibanda says.

“But of course I was disappointed. It was very medical and there was such an emphasis on prescribing medicine – giving anti-depressants and anti-psychotics for everything. There was minimal talk therapy.”

Chibanda grew increasingly frustrated with the system and his frustration only turned to grief when one of his patients, Erica, took her own life.

“One day Erica’s mother called to tell me that her daughter had hanged herself from a mango tree. When I asked why they hadn’t come to see me for review, her response was: ‘We couldn’t come because I didn’t have the bus fare’,” he says.

“They didn’t have the $10 to get on the bus and get to the hospital. With that I realised I shouldn’t be practicing mental health in a hospital – I should be going to communities like Erica’s to provide services.”

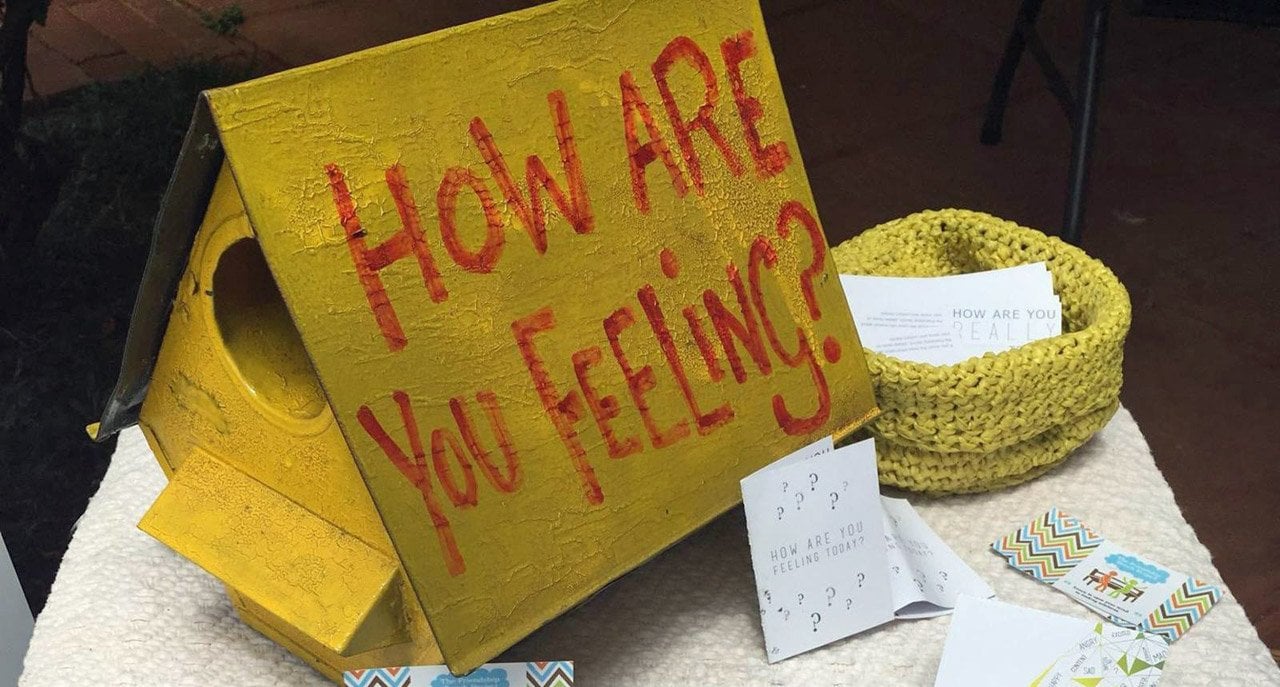

This eventually led Chibanda, who is an Associate Professor of Global Mental Health at LSHTM, to create the ‘Friendship Bench’ in 2006.

The Friendship Bench is a platform – literally, a bench – that creates space for healing through storytelling, and is anchored in evidence-based talk therapy. In Zimbabwe, the Friendship Bench began by recruiting ‘grannies’ – middle-aged or older women with little education who earn a small stipend doing community health work. The grannies are given four weeks to learn what depression is, how to diagnose it using a simple questionnaire and how to do a form of problem-solving therapy.

“I see elderly people as a very powerful tool to reach out to communities because they are the local custodians of wisdom and culture. They are brilliant at creating space and making people feel comfortable to opening up and developing a rapport. If you can develop a rapport and enable a person to share their story without fear of being stigmatised, it can make a huge difference,” Chibanda says.

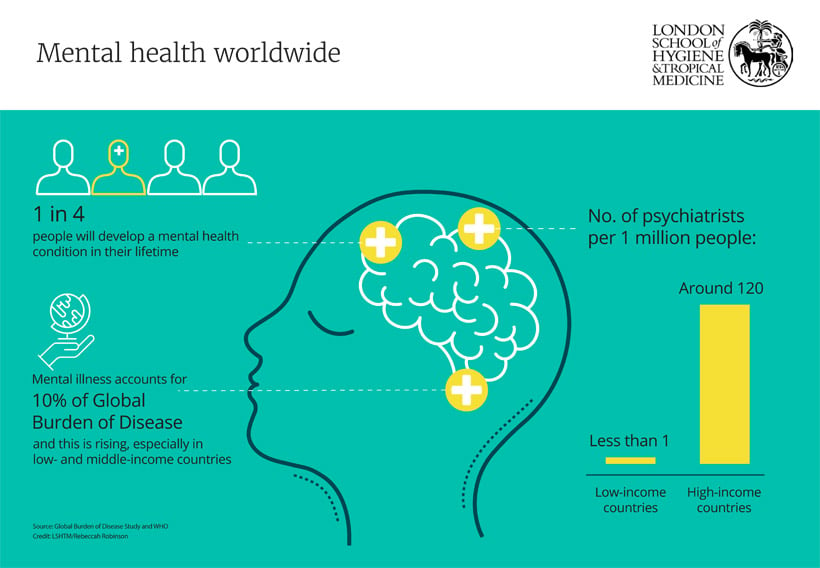

“Zimbabwe has 15 psychiatrists – the ratio is 1 psychiatrist to more than 1.5 million people... that’s where the Friendship Bench contributes significantly to narrowing this gap.”

Scaling up mental health care

Since 1948, health has been defined in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) constitution as: ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.’

Globally, hundreds of millions of people are affected by mental illness. An estimated 300 million people are affected by depression, and it is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide according to WHO. Every year, almost 800,000 people die due to suicide, making it the second leading cause of death among 15-29 year-olds globally. For every suicide, there are the countless families, friends and communities who are left behind and who experience long-lasting effects of such a tragedy.

The majority of those living with mental health conditions do not receive the care they need, particularly in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs). The reasons for this are complex but include a global shortage of health workers trained in mental health, a lack of investment in community-based mental health care and deep-rooted stigma and discrimination.

In low-income countries overall, the ratio of mental health workers can be as low as 2 per 100,000 population compared with more than 70 in high-income countries.

Given the striking inequity concerning the disparities in the provision of care, experts wondered: How can the gap be bridged using innovative, accessible solutions?

“We know that there is a huge need for more mental health care in Africa. In many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, more than 90% of people with a mental illness don’t get treatment, even the severe cases. That’s something that is never going to change without fundamentally rethinking how we deliver care,” says Dr Julian Eaton, co-director of the Centre for Global Mental Health at LSHTM.

One of the ways the Centre is aiming to address this challenge is through the Mental Health Innovation Network, which it leads in partnership with WHO. The MHIN is a community of mental health innovators from around the world, sharing innovative resources and ideas to promote mental health. It currently has more than 5,000 members and profiles 160 innovations, of which the Friendship Bench is just one.

Dr Eaton’s current research (also profiled by the MHIN) focuses on integrating mental health into primary health care in Nigeria. He explains one approach that is gaining traction: “We can’t put specialists everywhere, but a promising solution is task-shifting: a qualified nurse providing good quality basic treatment for people at primary health care level.”

More than a decade ago, WHO recommended that mental health be integrated into primary health care – the first level of contact with health systems – so that it becomes more readily accessible, affordable and less restrictive.

“We know task-shifting works but there’s a lot of investment that is needed and we need to move with urgency like we did with HIV,” Dr Eaton says.

Dr Patel was one of the first researchers to demonstrate the efficacy of task-shifting for mental health care in a LMIC setting. Task-shifting involves sharing the management of chronic conditions between specialists, such as psychiatrists and psychologists, and non-specialists, such as community or lay health workers. Using a stepped care approach, in which there are various ‘steps’ or levels of care, the most intensive care is reserved for the most severe cases.

“The idea is that people get a basic level of care before being referred. The problem with being referred too quickly is that few people make it to the next level. One of the challenges with this is that often primary health care workers feel more comfortable with administering drugs rather than talking. They are not used to the idea of non-drug treatment being effective and the population often also believes that,” Dr Eaton says.

But, as he stresses, using non-specialists to provide simple mental health care treatment does not eliminate the need for secondary care centres or national centres of excellence. “Primary care can’t provide complex care. We have to be careful not to undermine those very fragile services that are doing that.”

Another issue is the risk of over-burdening non-specialist health workers with too many tasks, particularly with the rise in non-communicable diseases that many have now also been asked to cope with.

Nevertheless, Dr Eaton says task-shifting provides an opportunity to engage with those working on the ground to address fear and stigma around mental health to change attitudes and make people more empowered.

Dr Dévora Kestel, director of the World Health Organization’s department of mental health and substance abuse, believes health systems in LMICs are ready to integrate mental health into primary care but cautions that more efforts are needed to strengthen their ability to actually do so.

“It is not enough to have a few people trained and committed. A proper system of care is needed, including support by specialists who could take care of severe cases and support for lay health workers,” she says.

“If there is a policy decision to integrate mental health at the primary health care level, other policies enabling this decision should also be considered such as reviewing criteria for prescription of certain drugs, understanding the workload of practitioners and identifying modalities for task-sharing.”

Innovative approaches to put mental health care back in patients’ hands

As researchers continue to look for innovative ways to improve mental health care in LMICs, another solution has emerged: peer support.

For almost a decade, Eddie Nkurunungi has been sharing his experience with mental illness to support others.

After using mental health services for more than 20 years in both his home country of Uganda and the UK, including a seven-year stint at an inpatient psychiatric hospital, he considers himself an expert by lived experience.

In 2007, he was discharged from East London Hospital and returned to Uganda. Back home he became involved with a community-based organisation called HeartSounds, led by other people with lived experience of mental illness. The organisation partnered with East London NHS Foundation Trust and Butabika National Referral Hospital in Uganda on a project called Brain Gain. The two-year peer working scheme – which was extended to Brain Gain II – trained people with lived experience to provide ward-based outreach in Kampala as well as home visits to outpatients in the Kampala, Jinja, Mukono and Wakiso districts.

“Being a father to a daughter and being aware that mental illness can run through generations, I thought it befitting to give back to the community and my peers some of my wealth of knowledge and experience in mental health,” Nkurunungi says.

The Brain Gain projects have led to a five-country trial of peer support called UPSIDES, which will generate evidence on how to implement empowering mental health services in non-Anglophone and LMIC settings, including Germany, Israel, India and Tanzania, as well as Uganda. For Nkurunungi, who manages peer support workers in a Ugandan hospital, providing peer support not only promotes recovery among patients, but gives a sense of purpose.

“Peer support gives people we speak to a sense of hope that recovery is possible. It builds self-esteem and confidence. The peers gain acceptance of self and the community at large. By speaking to peers we enable them to come out and challenge and fight stigma. I see peer support as my social responsibility and contribution to my community at large.”

Eddie Nkurunungi, Peer support worker, Uganda

Grace Ryan, a research fellow at the Centre for Global Mental Health at LSHTM and PhD candidate who has worked with Nkurunungi on Brain Gain II and UPSIDES, says peer support offers an opportunity for people to break out of the cycle of poverty and mental illness that affects so many.

“With peer support, we’re saying: why can’t those who have lived experience leverage their experience in order to help other people?”

“In resource scarce settings, it’s difficult to get a job so being a peer support worker offers a way to feel productive, gain self-esteem and get experience. People need opportunities to lift themselves out of poverty and this can be a pathway to paid employment.”

One of the most profound changes Ryan says she has seen in the field is the change in health care workers’ attitudes towards people with mental illnesses.

“Mental health workers sometimes hold the most stigmatising views of people with mental health conditions in LMICs but seeing how staff interact with peer support workers has been really cool. They say it has improved their attitudes and outlook on their own work,” Ryan says.

Dr Chibanda’s Friendship Bench is another innovative approach which not only strives to make mental health care more accessible, but one that highlights the importance of local interventions in that it was developed in the Global South and is now being adopted by high-income countries in the Global North.

The original Friendship Bench concept focused on people with depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder, but over the years it has expanded to provide a safe place for people who feel lonely too. The ultimate goal of the bench is to create a sense of purpose in people’s lives. And evidence shows that it’s working. In 2016, research published in JAMA found that patients with depression or anxiety symptoms who received problem-solving therapy through the Friendship Bench Programme were more than three times less likely to have symptoms of depression after six months, compared to patients who received standard care. They were also four times less likely to have anxiety symptoms and five times less likely to have suicidal thoughts compared with the control group after follow-up, the randomised controlled trial conducted by King’s College London, LSHTM, and the University of Zimbabwe showed..

The approach also challenges the Western model of mental health care that was exported across the globe.

“If you look at the terms that are used, they are very western. We don’t use terms like depression and schizophrenia unless I’m writing a research paper,” Chibanda says.

“There’s a school of thought among professionals which says that only clinical psychologists and psychiatrists can do this work. We teach our grandmothers cognitive behaviour therapy and train them to help those most at need in their communities as long as they know when to refer people on and how to identify a red flag like someone who is suicidal. It’s a stepped care approach.”

Ryan says the exportation of the ‘Western mental health system’ that is focused on institutionalised psychiatric care again highlights why local, community-based innovations for mental health care are required.

“In postcolonial times, things haven’t changed that much so we’ve ended up with a quality of psychiatric care which is quite often poor and local alternatives that haven’t fully been harnessed and supported,” she says.

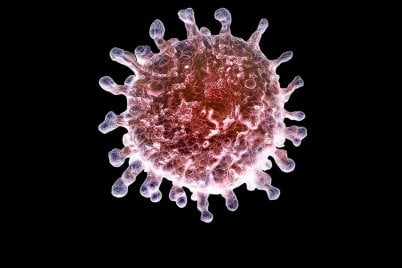

Engaging people with similar lived experiences of physical illnesses who are at high risk of developing mental health problems is another way to promote mental health and create a sense of community. One such example is HIV patients supporting other HIV patients.

“With the near universal access to effective antiretroviral therapy, HIV is now a controllable chronic illness. But this is conditional on being adherent to one’s treatment. Mental health problems such as depression compromise adherence to antiretroviral therapy and hence cannot be ignored in the fight against HIV,” Professor Eugene Kinyanda, head of the mental health project at the MRC/UVRI and LSHTM Uganda Research Unit, says.

To this end, in Uganda, where HIV is at epidemic level and up to one in three patients show signs of depression, the Medical Research Council Unit and Uganda Virus Research Institute (which joined LSHTM in 2018), has been undertaking research to understand and develop interventions for mental health problems in people living with HIV for the last 12 years. Current research is looking at developing a model for depression management that trains peer counsellors (patients living with HIV) to offer psychotherapy under supervision by health workers. Preliminary findings from the pilot study are encouraging.

“Depression scores among patients living with HIV are going down,” Professor Kinyanda says. “Patients feel that because the peer counsellors can empathise with them, they understand them better. Through funding from the Wellcome Trust we are going to subject this model to a clinical trial so that we can demonstrate that it actually reduces depression.”

From a research perspective, mobilising the voices and experiences of people who have had lived experience of mental illness not only helps to inform more effective research, but it also helps to develop policies that are more in tune with community needs.

“By giving people a shared activity, a space, an agenda, they start to advocate in exciting ways,” Ryan says.

However, she stresses that despite the urgent need to scale up mental health care, there is a risk of taking a top down approach and bulldozing community resources that do exist.

“We need more user-led research and delivery to ensure that global mental health has a conscience and is working to support local communities. As much as task-sharing interventions are good and have an incredible evidence-base, there’s no silver bullet solution that will work for everyone. We must go back to basics and put power into the hands of those who are directly affected.”

Grace Ryan, Research Fellow in LSHTM’s Centre for Global Mental Health

Educating the next generation of global mental health leaders

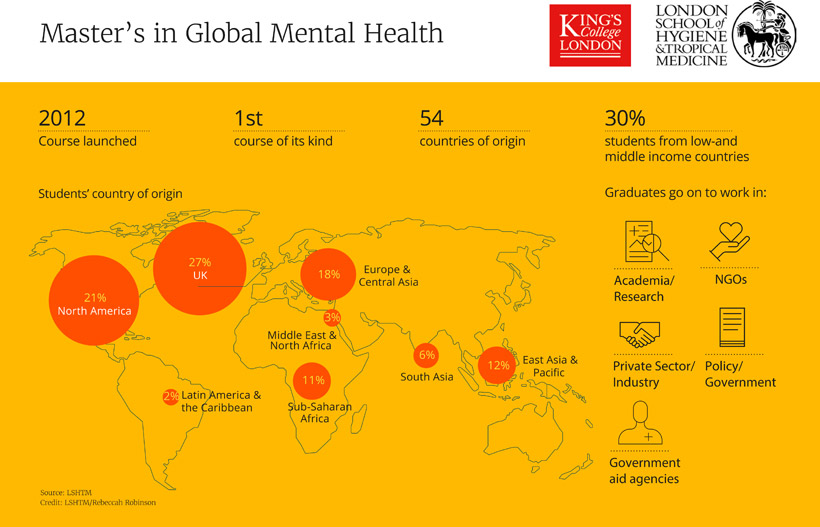

Recognising the need for degree-based training in the field with the increasing attention on mental health and the importance of strengthening mental health systems worldwide, in 2012 LSHTM and King’s College London commenced the first course of its kind in the world: A Master’s in Global Mental Health.

The MSc programme, of which Ryan was part of the first cohort, was developed not to address the human resource shortage in global mental health from a clinical perspective, but from a policy, leadership and research perspective.

Dr Ritsuko Kakuma, co-director of Centre for Global Mental Health and LSHTM programme director of the MSc, says it takes a holistic approach to mental health, rather than the historic focus on clinical care alone.

“If we don’t address the social components of mental illness … we’re not going to achieve what we want to achieve,” she says.

“Our aim is that our alumni have a holistic understanding of the risk factors and consequences for mental ill health so they can see what they can contribute to this field and can mobilise others who can also contribute.”

Students come from a diverse background – from public health and medicine, to anthropology, psychology and social work. Moreover, the course is increasingly attracting people who’ve set up their own NGOs and who want to develop their skills and go back to their communities to put them to use.

The MSc, which accepts just 50 students a year, almost half of whom came from low-and middle-income countries in this year’s cohort, covers a broad range of topics including mental health and conflict, climate change, human rights and disabilities, and how to design and evaluate mental health interventions which are culturally appropriate.

A large proportion of students stay on in research but many go on to careers at local and international non-government organisations, in addition to working in policy and at global institutions like the WHO.

“The diversity of the experiences and national identities the students bring to the MSc is the most enriching component of the course and we, as educators and researchers in global mental health, learn just as much - if not more - from them as they do from us,” Dr Kakuma says.

Ryan was drawn to the MSc because it had professors teaching who had experience in low resource settings and who worked directly with NGOs on the ground.

“LSHTM is an academic institute with a real focus on making an impact globally. It’s not an ivory tower. It does high quality evaluation and research but still has a foot on the ground,” she says.

With an increasing number of academic institutions offering degrees in global mental health, LSHTM and KLC are discerning how their course not only fits into the field but also how it’s contributing to creating a cohort of emerging leaders in mental health – leaders who can apply what they’ve learned appropriately in the context in which they work.

“One of the priorities is to incorporate lived experience into the programme – both in terms of the curriculum, as well as to foster an environment where the rich perspectives of the students who are open about their own personal diagnosis or in their role as carers are valued and encouraged,” Dr Kakuma says.

“We need to ensure that people with lived experience can contribute to policy and strategies. They should be at the discussion table. How do we develop research that builds on their experience and expertise?”

Mental health is a rights issue

To this end, the Centre for Global Mental Health is focused on addressing inequities by closing the care gap in poorer communities and countries, and by reducing human rights abuses by enabling people affected by mental health disorders to exercise the full range of human rights and to access high quality, culturally-appropriate health and social care.

From people shackled in chains, to women being sexually abused, to people left homeless on the streets because their families cannot cope, the human rights abuses that many with severe mental illness suffer is nothing short of shocking. Such practices must be challenged, Dr Eaton says, regardless of where they come from.

“We need to engage with traditional and faith-based leaders to challenge population attitudes but we need to be careful not to criticise,” he says.

This means viewing mental health as a rights issue, which requires taking a holistic approach that involves engaging with multiple sectors including the legal and criminal system.

“We need to recognise that putting people and communities in charge of their healing process is an equity and rights issue. What that means for us in practice is that we must focus not only on working with governments to form legislation that protects and promotes these rights, but also strengthening individuals’ capacity to access those rights,” Dr Eaton says.

Dr Kakuma says that part of taking a human rights approach to mental health means ensuring that people have equal opportunity to access physical health care too. That means working with other clinical professionals to reduce the risk of premature mortality and collectively addressing the rights of people with mental health conditions.

“We need effective and efficient health systems strengthening because working together only improves our efforts. We’re getting there; the momentum is there and we need to build on it to make sure the different fields work together.”

Access to mental health care has never been more critical and there has never been a better time to capitalise on the traction mental health has gained thanks to the tireless efforts of those who are dedicated to the field. While mental health and well-being has been included as a health priority in the global Sustainable Development Agenda, researchers say now is the time to translate talk into resources and political will.

“We’re at an exciting place. We’re right on the cusp of a revolution. We are not where we were 10 years ago. The foundations have been laid and we can be pretty proud of that,” Dr Eaton says.

Back in Zimbabwe, Chibanda is thrilled that the Friendship Bench has not only been endorsed by his government as a useful health programme, but that his intervention has crossed borders to other African countries and even to New York City.

It’s also caught the attention of global leaders. Earlier this year at the World Economic Forum, leaders in global health, politics and business sat side by side on the bench at Davos.

“My big dream is to see the Friendship Bench thrive in every country,” Chibanda says. “I’d like to see that everyone everywhere has someone to talk to. We will never have enough psychologists and psychiatrists but we can ensure the first port of call for anyone with a mental health issue is at the community level.”

We hope you enjoyed reading about our work in this feature. If you are interested in supporting projects like these and the many others we are leading to improve health worldwide, we would be delighted to hear from you. There are many ways you can make a gift to the School, from wherever you are in the world. Each and every gift we receive makes an impact, from funding scholarships, to updating our facilities or investing in new avenues of research. Whether it’s a gift of £5 or £500,000 your generosity will support our mission to improve health in the UK and around the world.