Developing a protocol for an evidence synthesis: lessons from Cochrane and realist reviews

This blog post includes subheadings to enable you to refer easily to particular topics or questions of interest, which include useful links.

On June 16, the first seminar of this new series focused on developing a protocol for an evidence synthesis. It hosted panellists Dr Jane Dennis, Editor for the Cochrane Injuries Group at LSHTM who has also worked as a systematic reviewer herself at the University of Bristol, and Daniel Carter, a Research Fellow and PhD candidate in the Department of Public Health, Environments and Society at LSHTM.

Populating the protocol for a systematic review: minimum standards in context – Dr Jane Dennis

This guidance is particularly focused on clinical topics and some elements may be less applicable to those focusing on social programmes or policies.

Jane began the seminar with a presentation on systematic review protocols drawing from her experience from within and outside of Cochrane.

First, she provided a useful reminder of the benefits of systematic reviews:

- Their ability to synthesise unmanageable quantities of information: as of June 2021, there were 1,777,773 reports of RCTs in CENTRAL alone!

- Overcoming the limitations of single studies which rarely provide definitive answers.

- Two key words stood out: explicit and reproducible (perhaps it is worth making a note of these when writing our MSc projects).

Moving on to protocols, if we were to retain one message it is that a “meta-analysis is optional in a systematic review, a protocol…. is not”. Dr Dennis used a wonderful analogy to illustrate this concept further: a protocol is “not cement… just a recipe”. A protocol should not just be seen as binding but rather as a means of increasing the reader’s trust and ensuring you are guided by your research question, not the data obtained.

Why publish your protocol?

- To prove to journals and readers that you have minimised bias in your review process by ensuring transparency, reliability and a comparison with your original plan.

- To avoid duplication of work by assessing what research is ongoing in your field.

When to register your review or publish your protocol?

- Before data extraction has started! After this, it may be too late as you may have been biased by seeing your search results.

What to include in your protocol?

RevMan software (on the Cochrane website) contains useful protocol and review templates.

- Background

- Description of the condition: include prevalence and incidence estimates if possible.

- Description of the intervention: in the context of other interventions.

- How the intervention might work: consider (biomechanical) pathways if possible, hypothetical pathways are an alternative.

- Why it is important to do this review: place your research into context with other work:

- What unanswered questions may your review help answer?

- Is there an older review that needs updating?

- These questions should be repeated again once your review is completed to place your findings in context, highlighting agreements and disagreements with other reviews.

- Why it is important to do this review: place your research into context with other work:

- Criteria for considering studies for your review: these questions drive your review design and are structured by the PICO(S) framework (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome and Studies):

- Type of participants

- Types of interventions

- Type of comparators

- Types of outcome measures: for clinical topics and when working according to GRADE Cochrane ways of working, restrict the ‘summary of findings table’ to seven outcomes. One must be ‘harm’ or unanticipated effects.

- Type of studies: considering the increase in trial fraud, reviewers now often only include studies pre-registered in a clinical trials register, providing proof of protocol pre-registration and ethics approval.

- Search methods: “your review is only as good as the evidence you looked for”.

- Always search clinicaltrial.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trial Registry for evidence of trial pre-registration for clinical topics.

- Other databases of interest for clinical topics may include:

- The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

- Ovid MEDLINE

- Embase

- Web of Science

- Subject specific sources

- Study selection plans: 2-3 reviewers should be involved to improve transparency and reduce mistakes (this is not permitted for MSc projects).

- Data extraction plans

The following sections should also be completed in a protocol, but are specific to the type of review:

- Assessment of biases – see the bibliography at the end of this summary

- Evidence synthesis plans

- Contribution of authors

- Potential conflicts of interest

PRISMA-P is a reporting guideline but can also be a useful guide while developing a protocol.

Where to register your protocol?

- For systematic reviews: PROSPERO

- For scoping review protocols: Open Science Framework (OSF)

How should conflicting findings be managed?

- Consider a meta-regression. You can rarely attribute differences to one thing.

- You should not have an opinion about what the findings will be (to minimise bias).

An introduction to realist reviews – Daniel Carter

Daniel provided an introduction to realist reviews, a concept that many of us have heard about but may not have yet fully understood.

Critical realism considers that the way we produce knowledge is mediated by our own experiences (subjectivist epistemology – what we know) and aims to consider the ‘real’ (realist ontology – what exists).

Some may still be a little confused at this point. However, Daniel proceeded to clearly explain that realist reviews aim not only to describe what works, but also to explain why and how an intervention works: “realist reviews should be thought of not as a methodology but rather a theoretical approach to a question”.

How are realist reviews different from classic literature or systematic reviews of effectiveness?

Examples of key realist questions:

- How and why does it work?

- For whom does it work?

- In what context does it work?

Realist reviews do not just aim to link pieces of information to understand effectiveness but have an explanatory aim to generate wisdom.

- Standard literature reviews do not necessarily aim to understand causal mechanisms.

- Systematic reviews can be implicitly realist and it may simply be that we do not have the realist vocabulary to explain our realist findings!

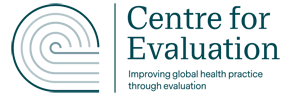

What are key concepts of critical realism?

Critical realism is about context. Daniel explained that the observable world should be studied but most importantly, ontological depth, or the observable world’s underlying mechanisms, should also be considered. This is more difficult as these are present “beneath the surface”, as illustrated by the iceberg below.

Source: Jagosh, J, 2019

Realist reviews aim to determine CMOCs underlying issues of interest. But what are CMOCs? They represent a combination of:

- Context (elements in the background allowing the exposure to impact the outcome)

- Mechanisms (the way in which the outcomes emerge; resources offered through a program and the way people respond to those resources)

- Outcomes (the observable part of the iceberg, the intended and unintended effects)

- Configuration

An example of switching on a lightbulb helped illustrate this: the lightbulb is the outcome; the context is the lightbulb being turned on by electricity only if the power grid supplying it is working; the mechanism is the electrical circuit.

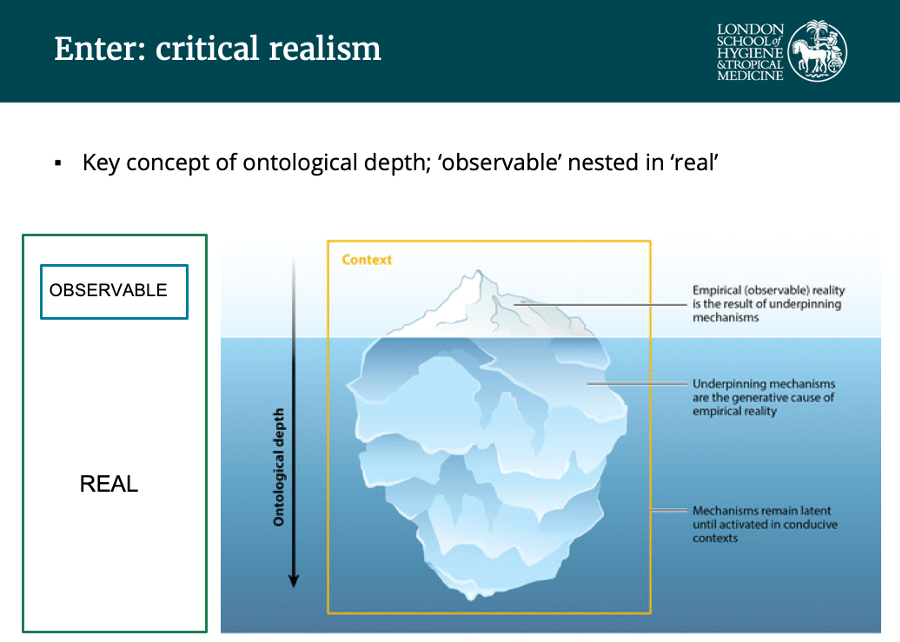

What are the steps of a realist review?

Daniel also highlighted that there is no one single way of conducting a realist review, a characteristic that enables them to approach complex problems.

Most steps are similar to a systematic review, as is the need to publish a protocol. The main difference is the philosophical realist lens the reviewer uses, also affecting methodology.

This is illustrated by the initial step of “programme theory” development which helps determine how you expect a particular intervention or exposure or policy to work on a given outcome (CMOCs) and is reviewed iteratively. This is comparable to a logic model or theory of change. Often, several programme theories are hypothesised that pattern together to produce particular outcomes.

How should conflicting findings be managed?

- Finding contradictory evidence does not invalidate your review. To the contrary, it can test the initial programme theory, refined via an iterative process.

- Compare the context of the contradictory findings – this might highlight the role of context and how the intervention should be delivered.

Useful resources:

Realist Reviews

- Jagosh, J., 2019. Realist Synthesis for Public Health – Building an Ontologically Deep Understanding of How Programs Work, For Whom, and In Which Contexts. Annual Reviews. Available from: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/pdf/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031816-044451

- RAMESES II guidelines for realist evaluation

- Dunn & O’ Campo (2012): Rethinking Social Epidemiology

- Pawson & Tilley (1997): Realist Evaluation

The recording of the session is available here. I definitely recommend taking some time to watch it!

This blog entry was written by Emma Cahuzac - MSc Public Health Student.

The Centre for Evaluation’s Student Liaison Officers would like to thank all panellists for their time, all students for their interest, and Laurence Blanchard and Delia Boccia for organising this seminar series.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.