Reviewing complex qualitative data: new approaches

The second of the four-part seminar series exploring evidence synthesis took place on the 30th of July. We were pleased to welcome Dr. Salla Atkins, Associate Professor at Tampere University (Finland) and the Karolinska Institutet (Sweden), and Prof. Chris Bonell, Professor of Public Health and Sociology at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Part 1: Dr. Salla Atkins - Getting meaningful results from sampling in qualitative evidence synthesis

The problem: an ever-increasing number of eligible papers

This talk was an interesting look at the challenge of having larger numbers of available research for qualitative evidence synthesis and how sampling can be used to manage this. Dr Atkins started by highlighting why we do qualitative research syntheses. They allow us to pull together qualitative evidence to inform practice and future interventions about a particular issue or to generate new theories about how interventions work. One of the challenges of doing qualitative reviews is the ever expanding number of potential papers to include, which are often of varying quality. Sampling is one way to approach this, which Dr Atkins explored through two cases.

To put us in context, the first example was a study published in 2007 by Munro et al. The main aim of this study was to understand the factors considered important by patients, caregivers and healthcare providers in contributing to tuberculosis (TB) medication adherence. 19 databases from 1966-2005 were searched, producing 7814 records, of which 44 were included and synthesised. Dr Atkins highlighted that a simple search was constructed using the terms “tuberculosis” and “adherence or concordance”.

By contrast, the second and more recent example is an ongoing review by Dr Atkins and colleagues (whose protocol is published here). The main aim of this review is to explore how conditional and unconditional cash transfers aimed at impacting health behaviours are experienced and perceived by recipients. Databases were searched from 1990 onwards. 7292 citations were assessed for eligibility, and a systematic process lead to the inclusion of 128 papers in total.

For this study, the institution’s librarian and the Cochrane group were involved in the development of the search strategy, meaning that the search was very specific and well defined. So, by contrast with the 2007 example, 7814 studies from a broad heading search were retrieved in 2007 versus 7292 articles from a highly specific one in 2021, highlighting the exponential growth in publications over this 15-year period!

Sampling strategies; what’s the big deal?

Dr Atkins argued that this exponential growth underlines the need for good sampling strategies to produce meaningful and beneficial qualitative reviews:

- 128 papers are too many to make for good analysis

- Even though software like atlas.ti can help with the analysis, more filtering is needed

For qualitative reviews, the aim is to explore variations in concepts rather than produce homogeneous results. Knowing that a need exists for sampling in qualitative synthesis, key questions about how to approach sampling were asked. If we use a sample of eligible papers, can this exclude potentially valuable data? Would selection based on quality criteria risk excluding important contributions from papers that may be of lesser quality?

With these questions in mind, a sampling strategy needs to be chosen. Salla explained that these are similar to those used when conducting primary qualitative studies. Examples are;

- Extreme or deviant case sampling

- Intensity sampling

- Maximum variation (heterogeneity)

- Homogeneity

- Typical case

- Purposeful random sampling

- Convenience sampling

What did they do?

For this 2021 review, the authors wanted to highlight that different groups of interventions (i.e., different types of cash transfer approaches) function in different ways e.g. economic based “nudge” theory to modify a particular behaviour versus unconditional cash grants which follow more a human rights approach.

The study group aimed for maximum variation in terms of geographic spread, type of grant used and health conditions. Each eligible study was coded for health conditions, HIV, TB, disability, reproductive and maternal health and mental health. On the other hand, part of this narrowing down process involved careful consideration about what to exclude. In this case, studies exploring “wellbeing and nutrition” were excluded as they didn’t match with other conditions. A difficult but important decision-making process!

From the 128 papers eligible, 43 were included. They covered interventions using conditional, unconditional cash transfers as well as a mixture of both. They also found that using this sampling strategy meant losing data on some countries, but reduced overrepresentation of others - in this case the United Kingdom and South Africa.

Reflections about the sampling strategy used

Dr Atkins reflected on the effects of sampling in her example.

- Variation in the concepts: The researchers wanted equal variety of issues covered. Sampling meant that certain issues were overrepresented, such as cash transfers for disability in the UK, despite a large amount of studies produced on the latter.

- Geographical representation gaps were generated. They noted that the whole Eastern Mediterranean region and several countries were excluded as a result of their sampling strategy.

- Sampling by quality of papers means potentially missing out valuable contributions by authors of low research capacity.

- Superficial results; is this a risk that comes with the inclusion of many geographical regions, even if the number of countries was reduced?

What about sampling papers based on quality assessment?

The importance of assessing quality, Dr Atkins later answered in a question from an attendee, comes from the fact that richness of description helps to build the interpretations used in qualitative evidence synthesis. Her experience suggests that poor quality studies contribute less to the body of evidence in an evidence synthesis than studies of higher quality. Quality assessment is, however, a contested issue in qualitative evidence synthesis. Although checklists such as GRADE-CERQual are used to assess quality, they still require a subjective assessment to be made by the researcher. Consequently, Dr Atkins argued that there is a need for further assessment of what quality assessment really means for the outcome of a review and that further research into the best approaches for sampling studies for inclusion in qualitative evidence syntheses among those eligible is required.

Part 2: Prof. Chris Bonell - Diagrammatic models for synthesising intervention theories of change, applying a meta-ethnographic approach

Professor Bonell presented this interesting and newly forming approach to synthesising evidence of theories of change. A theory of change is a description of why or how an intervention works (or is effective). It explains how change is thought to occur in the short, medium, and long term to achieve an intended (or unintended) impact. Chris began by explaining how systematic reviews traditionally synthesise impact outcomes, and sometimes process evaluation evidence, and that theories of change can also be synthesised.

Extracting information from theories of change in publications means having to explore descriptions with varying degrees of detail. Multiple descriptions of theories of change can be used to get an overarching idea of how a particular category of interventions works. This can then act as a template to develop one’s own intervention as well as inform further analysis e.g. of the mediators and moderators of an intervention.

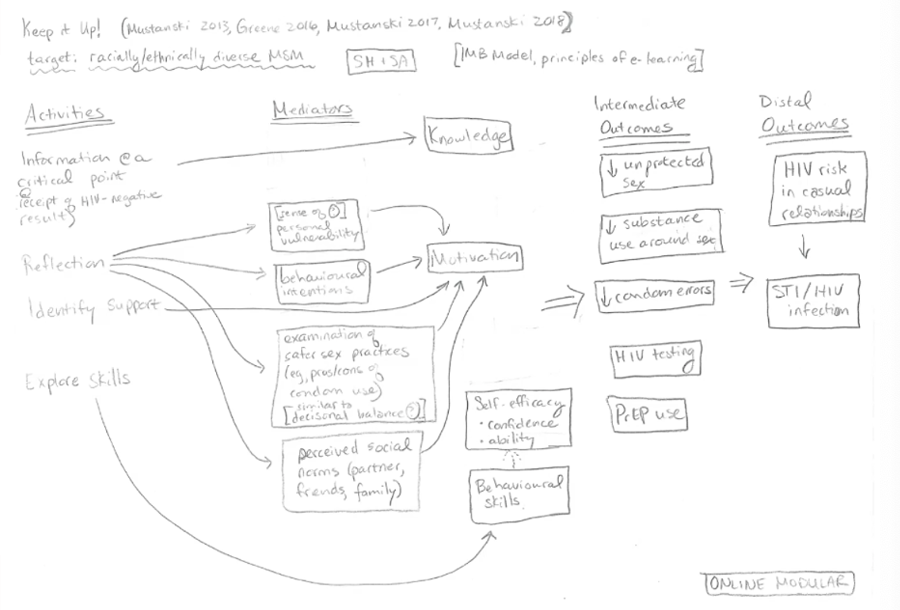

The example shared by Prof. Bonell was a review of E-health interventions (Meiksin et al 2021) to improve health outcomes for men who have sex with men (MSM).

A synthesis approach based on meta-ethnography

Meta-ethnographical methods were used to approach previous theories of change and provide a clear and systematic picture on how these interventions might work.

Interventions included in the synthesis were found mainly in the form of logic models or text, which in this case were specific and clear. Therefore, Chris and his colleagues decided to compare and synthesise information using a visual approach and by considering the different components of each theory. He highlighted that many of the studies included were recent, and therefore the use of logic models was more widespread, which made the theories easier to analyse. Older descriptions of theories of change that do not include logic models may provide more of a challenge to synthesise.

Three synthesis approaches based on meta-ethnography were used for this review:

- Reciprocal translation:

- Similar concepts across different accounts of theories of change in different reports are brought together as an overarching concept

- Refutational synthesis:

- Contradictions or opposing concepts occurring across theories of change are identified

- Line of argument

- An approach that aims to “piece together” concepts across studies

They produced a diagram for each set of eHealth interventions that fell under a particular behavioural theory and then combined these to form an overarching theory of change in one diagram. The results were then displayed in a delightful set of handwritten penciled diagrams (image below), including activities, mediators, moderators and outcomes. This was an interesting diversion from the hard straight lines of most published reports!

What they found

The studies were largely informed by different cognitive and behavioural theories which made them easier to categorise, such as the information-motivation-behaviour model and the social cognitive theory model.

Sometimes, creative ways to conceptualise differences in theories across studies had to be used to synthesise the data. Chris contrasted how the theories of change overlapped but also differed such as in the direction of causal flow regarding how the intervention produces change. For example, the eHealth intervention ‘MyDex’ (Bauermeister et al 2017) theorised that participants’ motivation lead to intention while the intervention ‘The Keep It Up!’ (Mustanski et al 2018) suggested the opposite, i.e. that intention leads to motivation. The authors managed this in their report by treating “motivation/intention” as a joint construct in a diagram, and used text to clarify how conclusions differed for this construct. Overall, going through this process for all eligible studies produced an overarching theory of change eHealth interventions to change health outcomes for MSM.

Lessons

Prof. Bonell wrapped up the interesting talk with some useful take-home messages:

- Diagrams are useful!

- Drawing on multiple reports of theories of change allowed for the development of overarching theories which were more nuanced than individual reports

- Overarching theory of change combined with synthesis of outcome evaluations provide a good starting point for developing new interventions in a particular area

You can watch the recording of the session here.

Author: Salma Hassan, MSc Public Health Student, LSHTM.

Revision: Laurence Blanchard, Co-lead for the Evidence Synthesis theme, Centre for Evaluation, LSHTM

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.