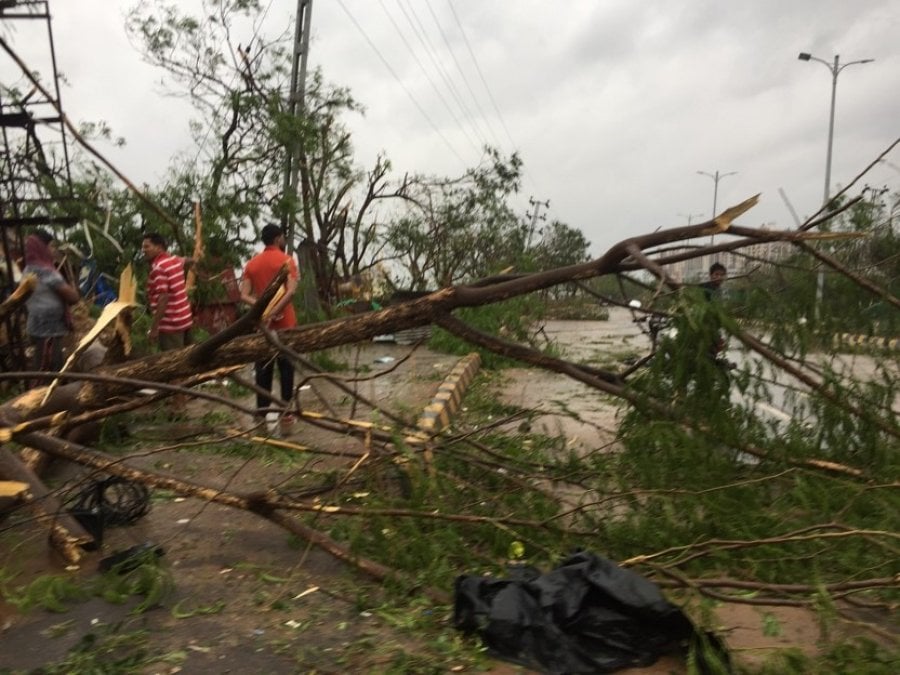

Roads ravaged by fallen trees due to cyclone Fani, 3rd May 2019. Image: Sneha Krishnan

Sneha is a Research Fellow at LSHTM.

On May 3, the Indian states of Odisha, West Bengal, and Andhra Pradesh were ravished by Cyclone Fani, an extremely severe summer cyclone. It was a rare storm, as only once before had such a severe cyclone hit the Indian mainland – in April 1966.

May is generally considered a dry season, with cyclones unlikely. As a result, people did not think it could be destructive and were reluctant to evacuate immediately. By the time it had wound down, Cyclone Fani had affected 16 million people across 18,388 villages and 51 towns in Odisha alone. Living in Bhubaneshwar not far from the coast, I witnessed first-hand the state government and media mount preparedness efforts. Millions of people were evacuated, not only along the coastal areas, but also in urban hubs which were expected to fall in the path of the cyclonic winds. In Barang, a peri-urban centre near Bhubaneshwar, police forcefully evacuated reluctant families to the school centres which had been designated as relief camps. A record 1.2 million people were evacuated in 24 hours, and almost 7,000 kitchens catering for 9,000 shelters were put into action overnight. This mammoth exercise involved more than 45,000 volunteers. India's Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, had agreed that $140m (£106m) was going to be allocated for emergency relief. Our househelp Sunita (name changed to retain confidentiality), who lived in the peripheries of the city and was evacuated, related stories of how more than 100 people had to just stand upright in the shelter as the cyclone passed, as there was hardly any space left on the ground for sitting or resting.

In the middle of the storm, we saw 125mph winds shattering glasses, doors and anything that stood in its way. With even higher winds of 175-185 km/h gusting up to 210 km/h on the coast, populations here suffered not only structural losses, but also power outages which lasted for more than 10 days.

With such heavy speeds, cellular coverage and water supplies were also affected. This made it incredibly challenging for relief teams to reach the worst-hit areas. With mobile phone connection down, at first the Collectorate (district administration) in Puri relied on a ham radio network. Although, like most Odiya people, I remember the destruction from the 1999 SuperCyclone, our memories were insufficiently useful for aiding faster recovery.

Within our own apartment complex, we heard glass shattering and became concerned about our elderly neighbours and those with small children. Braving the strong winds to go outside, we still found it difficult to prise open our neighbours doors against the wind, so we retreated back inside. When we finally could enter their flats after the cyclone had passed over us, we found their homes flooded, windows shattered, and many injuries sustained by shards of glass. Mahesh (name changed to retain confidentiality) sustained several injuries over his body when the glass shattered in his room, including his head and face, and his mother was also injured when she was trying to help him. As soon as the rains subsided, we had to seek medical support for them, but accessing any nearby health centres became a challenge, as the roads were waterlogged and trees had fallen, blocking vehicular traffic. When we finally made it to the hospital, most patients we met had reportedly been injured by falling window panes and roofs, or were otherwise hit by flying materials and collapsing walls. Official government reports placed the death toll at 41, 21 in the city of Puri alone. On May 15th, the Odisha government presented a preliminary report that put the losses at ₹11,942 crore (£135k).

Thousands of trees were damaged, destroying the power lines and disrupting access to the markets. Safe drinking water supply and sanitation services were some of the worst hit services. The tourist and religious centre of Puri are still struggling to get on their feet, as Jagannath temple – one of the main attractions – was damaged by the winds, including one of the idols. With ongoing election taking up most of the broadcast time, many have criticised the limited national media attention on the impact of cyclone and how people were affected. Adding to that, a post-cyclone heat wave combined with the lack of power forced many families to rely on generators for water and electricity. These are procured at steep prices (10,000 INR ~ £120). Those who could afford it left the city to take refuge at friend’s homes or hotels in another city, as Bhubaneshwar and Puri trudged along to get back on its feet, but many of the most vulnerable had been left behind.

What could encounters with past cyclones teach us?

After SuperCyclone in 1999, the Odisha Government had drafted a Disaster Management Bill for the state, simultaneously creating theOrissa State Disaster Management Authority,. Their main tasks were to exclusively deal with disaster mitigation and preparedness efforts in the state. They have led such efforts after Cyclone Phailin in 2013, Cyclone Hud Hud in 2014, and Cyclone Titli in 2018. I joined this response team with Oxfam as part of my doctoral studies in 2018. As a doctoral candidate for University College London, I was studying community resilience to disasters and how they recover from it, particularly in terms of water, sanitation and hygiene behaviours. There, I found that although the Government of Odisha was lauded for zero casualties after the 2013 Cyclone Phailin, it was systematically inefficient in addressing concerns of damages to water sources in marginalised, remote coastal villages and lethargic in terms of delays to the proposed reconstruction programme, which in the end hardly reached affected families in Puri. My study further found that although there were opportunities for improving many developmental issues such as water, sanitation and housing services, they were largely missed due to lack of convergence and integration between different sectors, departmental agencies and civil society. While recovery efforts are still on-going, we may be able to look back and study and analyse the response compared to previous ones.

However, during my research, there were some lessons learned which would be useful for reducing injuries and the overall impact caused by natural disasters in such settings:

- Rationing is extremely important. As soon as families receive message of an approaching cyclone stocking up food for families is the first and most important step. Individuals and families could be encouraged to do this with government messaging.

- In such instances, civil society members are often the first responders. As such, their provision of first aid and evacuation is important to help the survivors and injured, and training programmes to support them should be in place.

- Health and nutrition needs to be focussed on as the growth falters for vulnerable children during crises as a result of closure of schools. and anganwadi centres, which provide ready to eat meals to children. Access to food is also affected by lack of market access and the destruction of food crops and stored foods.

- Existing policies should emphasise immediate and longer-term WASH needs. They should equally invest in learning and innovation in water, sanitation and hygiene behaviour changes in order to prevent unnecessary issues during situations of high stress

- Existing manuals, policies and programmes should incorporate women’s specific needs and challenges during disasters, and be sensitive to their immediate as well as longer-term needs – for instance providing for safe spaces, latrines and bathing cubicles in the cyclone shelters.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.