Dr Susannah Woodd

I spent at least a year saying it shouldn’t be done. There wouldn’t be any data, or what existed would be of such poor quality that it would be meaningless. How many women suffer from infection during and after childbirth? We didn’t really know.

Did we really want to spend a lot of time and effort just to demonstrate our ignorance?

The trouble was, I was already working with a small team of researchers on ways to prevent these infections for mothers. Our rationale? That infections were a frequent and important problem. But at the back of my mind was the niggling anxiety that in reality they weren’t.

And so, eventually, my argument changed.

We needed to know the numbers to support both our and others’ research, to highlight whether or not infection was an issue to prioritise, and if so, to advocate for improvements in quality of care. So, I set about asking: how many women suffer from infection during and after childbirth?

Three years later the systematic review is completed and published. It took even more time and effort than expected – with over 31,000 articles to screen and over 100 included.

And yes, as I thought, a lot of the data are of poor quality, and very little comes from low- and middle-income countries. And yes, a lot of uncertainty still exists. But despite this, and contrary to what I thought, it is clear that infection really is an important problem for new mothers.

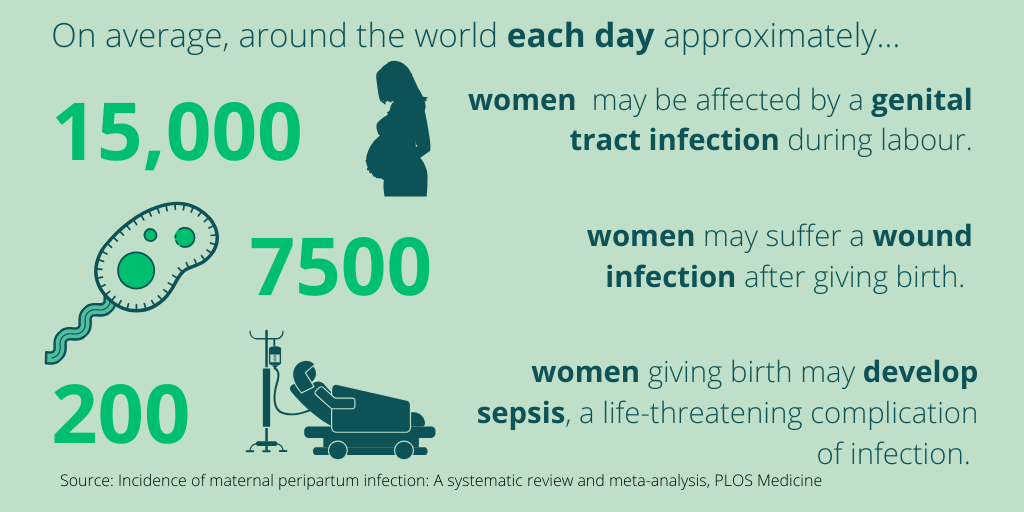

- Genital tract infection affects approximately 4% of women in labour – on average 15,000 women around the world each day – carrying risks for the baby as well as the mother.

- About 2% of women giving birth suffer a caesarean-section or perineal wound infection, that’s 7500 women a day.

- And on average 200 women giving birth each day develop sepsis, a life-threatening complication of infection.

What are the implications of this? Well, here are five views.

1. What infection means for women? A mother’s perspective

By Giorgia Gon, LSHTM

Having an emergency caesarean-section is not fun and not what I would have chosen, but I felt safe and in some of the best hands this world can offer. After all, I delivered in a hospital in London. Recovering from a caesarean-section again is not fun… I was immobile, in pain, and weak. But I was lucky that my partner, family and friends were around to give me a hand, in the most literal sense, of helping me to sit up for breastfeeding every hour.

But just when I did start to feel better… boom! Feeling low again, in pain again, less mobile again. Part of my wound was red, painful and did not feel right. It was infected. I received immediate care from my GP, but the infection set me back at least a couple of weeks in terms of recovering from the birth.

Throughout, I kept thinking how lucky I was to have delivered where I did… not to be one of thousands of women each year that give birth in low-resourced settings and develop infection without access to good-quality care and support. Yet, the type of care I received is not out of reach, but an achievable right for all women.

2. What can be done to prevent infection? Infection prevention and control (IPC)

By Wendy Graham, LSHTM

At last we have a comprehensive review highlighting the crucial role for primary prevention of infections around childbirth – reducing not only the health and financial burden on families and health services, but also the need for antibiotics – so reducing resistance. And we know that many of these infections are in fact preventable healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), including surgical site infections after caesarean. Poor aseptic technique, poor hand hygiene by clinical staff, poor environmental cleaning of the healthcare facility and/or lack of adequate water and sanitation can expose women and babies to pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus, leading to HAIs.

So why do we need to keep making the case for prioritising routine IPC? This seems perverse given the comparative simplicity of basic preventive practices, such as effective hand hygiene, routine disinfection of clinical surfaces, and appropriate disposal of waste. These practices have been known about for centuries and should now be routine in all healthcare facilities. Yet many women and newborns still do not have access to a clean and respectful environment in which to deliver. The hard evidence on the burden of maternal infections in this paper reinforces the urgent need to honour the Hippocratic oath “First do no harm” – prevent preventable infections with clean care. How more basic does it need to be?

3. How does unnecessary caesarean section contribute to risk?

By Ana Pilar Betran, WHO

When one performs a necessary medical intervention, such as caesarean section, to save the life of a mother or a baby, we accept the potential risks involved. However, conducting a caesarean when the mother and baby do not need it, a scenario that is increasing worldwide, appears to be irrational.

Yet, when it comes to a highly emotional process such as birth, it can be hard to accept uncertainty. The woman’s fear of pain, the provider’s fear of litigation, the convenience and control of scheduling the procedure, misconceived benefits, and lack of human resources can all explain the decision to intervene. A cesarean can appear to provide certainty and safety. However, despite impressive technical and medical advances, caesarean sections are not infallible. As this new review underlines, infection remains one of the important threats for women following a caesarean.

Reducing unnecessary caesarean section is a global priority. Initiatives need to address the concerns of all those involved, raise awareness of the benefits of vaginal delivery; improve communication with women and families; create a respectful environment during labour; pursue models of care led by midwives, and work with country parliamentarians and policy-makers. This is difficult, but essential, to ensure optimal maternal and newborn outcomes are achieved.

4. What is being done about maternal sepsis?

By Mercedes Bonet, WHO

WHO is committed to improving prevention and management of maternal infections and sepsis. And the results of this systematic review highlight the importance of this work.

Soon, WHO will publish results of the Global Maternal Sepsis Study (GLOSS). The study is one of our efforts to better understand the frequency and intra-hospital management of maternal infections and its complications in 713 health facilities in 52 countries.

Alongside the study, participating facilities implemented an awareness campaign aiming at improving health provider’s knowledge on detection and management of maternal sepsis. Surprisingly, two countries scaled-up the awareness campaign at the national level, again a marker of how important the issue is, in particular in LMICs.

Read more:

https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/maternal-sepsis-mexico/en/; https://www.ogmagazine.org.au/21/4-21/raising-global-awareness-on-maternal-sepsis/

5. What does infection mean for the newborn baby?

By Sarah Moxon, LSHTM

This review highlights maternal infection as an important cause of preventable morbidity for new mothers, with infection estimates of over 4% in labour. But how should we interpret these findings in view of the care for the vulnerable newborn baby?

Maternal infection during labour increases risks for the baby – higher risk of stillbirth, intrapartum complications, and transmission of infection via the birth canal. Facilities need to be prepared for the needs of these newborns, as well as their mothers. In addition to quality care during labour and delivery, and resuscitation of non-breathing babies at birth, there is the potential need for ongoing care for sick newborns, including appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent early newborn infection. The highest risk of newborn mortality is in the first 24 hours and the smaller babies face the highest risk; many will require inpatient care.

This review should also prompt us to think more broadly about respectful, nurturing care for newborns where their mother – their main advocate and source of nurturing and nutrition from protective breastmilk – is more vulnerable due to sickness. This important review yet again reminds us of the synergistic needs of mothers and their babies, especially in cases of complications during childbirth.

You can read Susannah's original research article here.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.