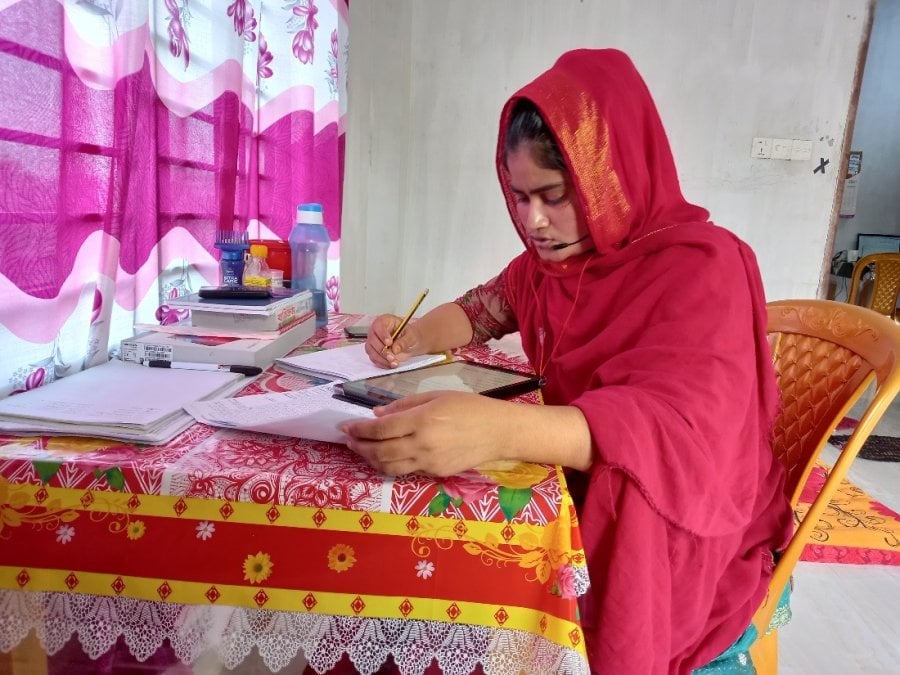

RaMMPs caller in Bangladesh. Credit: International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B)

About the Consortium (Malebogo Tlhajoane, LSHTM)

Can you tell us a bit about the RaMMPS consortium?

The Rapid Mortality Mobile Phone Surveys project, also known as RaMMPS, is a multi-country study that began in December 2020 with an aim to develop and validate methods for timely (excess) mortality estimation in low and lower-middle income countries (LLMICs) where suitable alternatives are unavailable. RaMMPS leverages the rapid expansion in mobile phone use in LLMICs to collect mortality data without the need for in-person contact. This approach is appealing because it is cheaper and could be used in settings affected by epidemic outbreaks or humanitarian crises where the mobility of interviewers may be restricted.

The RaMMPS consortium consists of 13 partner institutions, with fieldwork in five countries - Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique and Malawi. In most countries, the RaMMPS consists of a national survey and one or more validation studies that leverage another mortality surveillance system as a comparison data source. The experience with mortality mobile phone surveys is limited, so there is still a need for methodological and validation work in terms of sampling approaches and development of survey tools. For example, those who own a mobile phone are a select group who might not be representative of the general population, and thus, could introduce bias in the mortality estimates.

We’re supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (through an agreement with UNICEF-USA) with supplementary funding from the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office for the DRC RaMMPS, USAID for the Mozambique RaMMPS and institutional funding from NYU for the Malawi RaMMPS.

Why have you chosen these five countries (Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mozambique, Malawi)?

Several criteria played into their choice, ranging from need for mortality data on the impact of COVID-19, the expertise of in-country partners with mobile phone data collection and the availability of other data sources that could be drawn on for methodological validation studies. Each country case-study shares the same objectives; but RaMMPS methods vary slightly in each country in terms of sampling strategies, survey instruments used and external data sources for validation work. These differences are intentional to best leverage context-specific attributes of each RaMMPS and to better understand strengths and weaknesses of various approaches for measuring mortality via a mobile phone interview.

How can people find out more about the project?

More information about the project, including details on the methodology used in each country, can be found on the RaMMPS consortium website. There, you can also find links to each of our partner websites, live data dashboards with some preliminary descriptive results, as well as links to presentations and publications from members of the consortium.

RaMMPS Methods for Mortality Surveillance (Stephane Helleringer, New York University - Abu Dhabi)

Why are population-based mortality statistics important for public health?

For several reasons.

"These statistics help us to understand what health problems should be addressed with the highest level of priority."

First, these statistics help us to understand what health problems should be addressed with the highest level of priority. For example, from mortality statistics, we might learn that a particular disease or condition kills several times as many people as another condition in a country or region. Then, public health efforts might have the largest benefits for population health if they focus on that cause of death. So, it is key to have complete statistics so as not to "miss" any emerging or worsening health crisis.

One example of this comes from the COVID-19 pandemic. In countries with complete mortality statistics (mostly high-income countries), high levels of excess mortality were documented, at least during the first waves of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was used to justify extensive vaccination programs and other mitigation measures. In countries with limited mortality statistics (e.g., low-income or lower-middle-income countries in Africa or South Asia), available mortality statistics did not show a similar level of excess mortality. Many interpreted this as proof that low-income and lower-middle-income countries had been "spared" by the pandemic, and thus did not require similar access to vaccines, in particular. Of course, this lack of apparent excess mortality in many LMICs is also likely an artefact of incomplete mortality statistics. In fact, several studies using alternative data sources have now documented large spread of COVID-19 in LMICs, and associated excess deaths.

"Mortality statistics also help us learn about what works in public health."

Second, mortality statistics also help us learn about what works in public health, i.e., which interventions or programs might save lives. To do so, we would compare mortality statistics before and after the implementation of a public health effort, or we would also compare areas where an intervention is implemented to other similar areas where this intervention is not implemented. If mortality is lower in areas or periods where the intervention is not implemented, then we get some indication that the intervention is likely working and saving lives, and should be expanded to other areas.

What are the benefits of using mobile phone technology to collect these data?

"Mobile phone technology helps collect data faster; it might also help reach hard-to-reach people, more often... This is essential for public health."

Mobile phone technology helps collect data faster; it might also help reach hard-to-reach people, more often. Typically, in LMICs, mortality data are collected by visiting households and asking a household representative a few questions about deaths among their relatives. From these data, we can estimate recent levels of mortality. But, unfortunately, it takes enormous efforts and resources to reach households disseminated throughout a country. Some areas may also be difficult to access, for example, due to bad roads, ongoing conflicts, or acute health crises (e.g., epidemics). As a result, we only conduct such surveys or censuses every few years, and we have no idea how mortality evolves in-between.

Because the coverage of mobile phone services is so high now in LMICs, and many households own at least one mobile phone, this technology allows reaching people throughout a country much more frequently, even if they are in areas that are in conflict, under quarantine or otherwise hard-to-reach. We can thus produce mortality statistics on a regular basis and follow short-term fluctuations in mortality. This is essential for public health.

Has mobile phone technology been used for anything like this before?

Mobile phones have been used to measure mortality during the Ebola outbreak in west Africa and during recent conflicts such as the one ongoing in Cameroon. Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, such surveys have also helped show that the death toll in India was likely much larger than the reported death toll. These projects were, however, limited to trying to record a specific type of deaths, e.g., COVID-19 deaths.

In Malawi, we have also tested whether mobile users might experience negative reactions when asked about recent deaths in their family. This might indeed be a question that triggers distress or sadness. In a trial where we asked some users to complete an interview about recent deaths, and other users to complete an interview about their recent economic activity, we found that very few respondents reported experiencing sadness or distress during the interview. Furthermore, those who were asked questions related to deaths did not experience sadness or distress at a higher rate than those who were asked economic questions. Since economic questions are widely considered as acceptable to ask during mobile phone surveys, this comforted us that mobile phone surveys of mortality could indeed be conducted on a large scale. The RaMMPS project is now much broader in its objectives, as it seeks to detect deaths from any cause, using very comprehensive survey questionnaires.

In-country Partner Experiences (Cremildo Manhica – INS RaMMPS Mozambique)

What is your role as an in-country partner?

My role as an in-country partner is focused in managing overall study activities within the country and ensuring that the study is being conducted in accordance to protocol and the good clinical practices. This includes handling tasks such as designing data collection instruments, training data collection interviewers, implementation of study protocol, monitoring progress of activities and employee performance, organising training programs, supervising operational budget management, work with the partners and timely reporting of results on a weekly basis.

Has COVID-19 had an impact on the project?

Yes indeed, during the first months of the project, the interviewers were forced to switch turns between working from home and office to avoid contracting COVID-19 which was a challenge. To maintain productivity and team morale, we rented another office so that we could ensure we made good progress toward the project goals, while adhering to COVID-19 prevention measures.

Do you have any preliminary results?

Although we do not have preliminary results from the main study, a pilot was carried out before the main data collection began, aiming to test the data collection instruments and the cost of implementing alternative sampling approaches. The pilot helped us to understand the feasibility of the interviews, select an appropriate tool for the mortality measurement, and address any challenges in the design of the main study. We found, for example that the phone interviews can take less than 20 minutes on average and the overall response rate was about 50%.

The pilot also helped us understand the cost of recruiting eligible respondents through a pre-recorded automated phone survey, also known as an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) survey. We estimated, for example, that it will cost about $1.3 to recruit an eligible respondent through IVR, and about $4.5 to complete an interview. All these results are currently being written up for publication.

How do you think these results will benefit you as a country partner, from a policy and programme perspective?

The findings from the RaMMPS study can help us in several ways.

First, we are currently generating mortality data through various sources such as SiS-COVE, a community sample registration system, and household surveys. The RaMMPS data will be compared with these sources for a better understanding of mortality disparities across the country. This will help in decision-making in national health plan and resource prioritisation; enable further investigation of causes of death, and fine tune policies for addressing cause-specific mortality.

Second, RaMMPS is a unique approach for rapid data collection on mortality. The lessons from this approach will truly help expand to other areas for disease surveillance, which is currently high priority for us.

These data can greatly help in decision-making to prioritise national resources with a focus on health, deepen the investigation of causes of mortality as needed and designing health policies that focus on controlling specific causes of mortality to reduce overall mortality and for priority groups.

What are the next steps?

The Mozambique RaMMPS was designed to collect mortality data in two samples. The first uses the COMSA (Countrywide Mortality Surveillance for Action) platform as the sampling frame. COMSA is led by the Government of Mozambique, and aims to produce continuous annual data on mortality and cause of death at a national and subnational levels. For the second sampling approach, numbers are dialled randomly with the aforementioned IVR, to establish the eligibility before conducting the actual RaMMPS interview.

Once the data collection has finished, we are planning to hold a data analysis workshop, write and publish a mortality report and a number of scientific journal articles focused on mortality mobile phone surveillance methods and cost. We will compare child and overall mortality between periods before COVID-19 (2018-2019) and during COVID-19 (2020-2021) to estimate possible excess child and overall mortality. After writing the report, dissemination of results focusing on policy makers and the general public to ensure data to action will deserve important attention.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.