Globally, an estimated 13.4 million newborns are born too soon (preterm) each year. The majority of these small, vulnerable newborns are born in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia and are at much greater risk of dying than babies born at term, especially due to difficulties with breathing, feeding and temperature regulation.

Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) is a method of caring for preterm or low-birth-weight babies that involves continuous skin-to-skin contact between a newborn and their caregiver (usually mother), as well as support for breastmilk feeding and early discharge. KMC has been shown to have major reductions on the risk of death by around 40% among stable babies weighing less than 2000 grams. KMC is strongly recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) for babies in all countries, and updated recommendations including babies prior to stability, based on a recent WHO-led multi-site trial.

OMWaNA, which stands for ‘Operationalising kangaroo Mother care amongst low-birth-Weight Neonates in Africa' , also means baby in Luganda, the local language. The trial, published in The Lancet, shares results on effectiveness and economic evaluation of KMC started before the baby is stable, when they are still needing other life-saving treatments, like intravenous fluids and breathing support.

The OMWaNA trial is the largest trial in Africa of KMC before stability, involving 2221 neonates from five government hospitals across Uganda, and the first to report on the cost implications of implementing such KMC. This research was funded by UKRI’s Joint Global Health Trials, led by MRC-UK. Researchers from across LSHTM, the MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit and Makerere University worked together on this ambitious research.

As the Trial coordinator in Uganda, I was recruited in 2019 and I helped to make sure that the sites were set up and safe to run the trial. Often in African hospitals, small and sick newborns are cared for in a tiny room with no space for caregivers, clinical staff or equipment. In several sites we had to build a new room, or expand existing rooms, all with limited funding. I was responsible for clinical training and for day-to-day support to the five hospital sites and teams, ensuring enough babies were being recruited, that protocols were followed, and data quality was high. This was a juggle given the distances between the sites and was especially tricky for all of us during the COVID-19 pandemic.

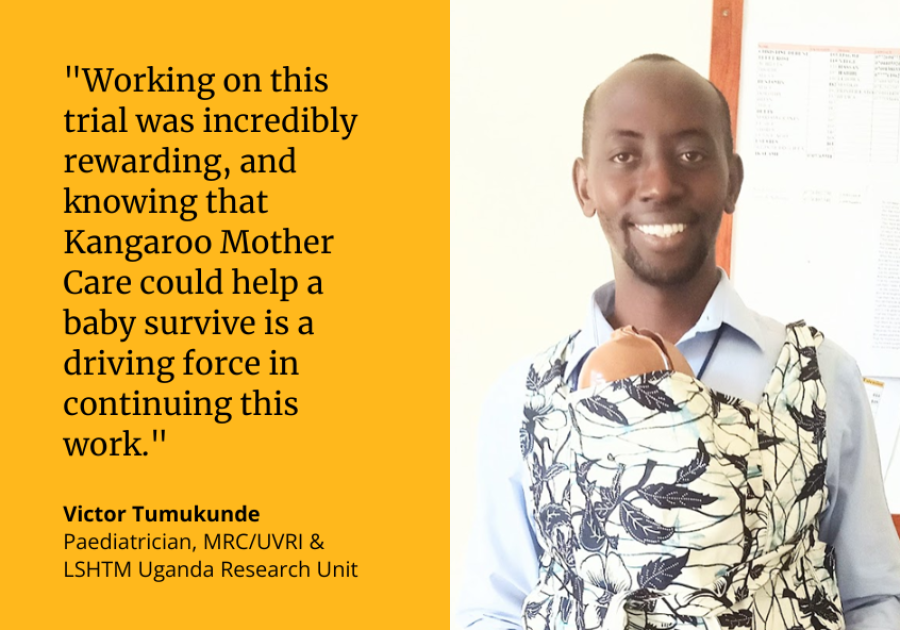

A particularly moving moment for me was when one of the hospital trial site paediatricians, Dr Sheila Oyella, had a very preterm baby at 29 weeks. I was able to help her to do KMC even when this 1390 g baby was still not stable and was particularly vulnerable. The baby survived and his family named him Victor after me, and because he was victorious! This is incredibly rewarding, and knowing that KMC could help the baby survive is a driving force in continuing this work.

OMWaNA also enabled me to do my PhD and I am especially interested in KMC duration – how long the caregiver can provide KMC per 24 hours before their babies are clinically stable. My work added to the trial and has been considering how to better measure duration and what can influence longer duration, such as having another family member present.

A personal highlight for me is being the co-first author on the paper in The Lancet and being part of the webinar to launch the paper with live translation into French. I look back to 2019 and would never have guessed this could happen. Now my focus is to finish my PhD and also to work with the government of Uganda on an investment case to try to catalyse more funding for faster progress for neonatal care with integrated KMC all over the country.

OMWaNA Trial Results

Like previous similar trials, OMWaNA did not show that KMC before stability reduced deaths in the first week after birth, however it did show a non-significant reduction in deaths by 28 days of age and when the results were combined with those from African sites of two other similar trials, we showed a 14% significant reduction in deaths by 28 days.

We also showed other important benefits such as reductions in hypothermia (reduced body temperature that adversely affects the heartbeat respirations and other vital body functions) and improvements in daily weight gain at 28 days which can be crucial for the small vulnerable babies.

Importantly, our trial is the first to report on the cost effectiveness of this early KMC. We found that KMC initiated before stability could reduce costs compared with standard care, even when considering the investments in floor space and devices that are required to improve the quality and safety of newborn care from current practice.

Moving forward, further research and trials are needed that focus on improving facility-based care of small and sick newborns in combination with KMC, and help us to better understand how best to implement early KMC at different levels of the health system.

Our research has outlined the benefits of KMC in addition to other care practices, but increasing budgetary allocation for small and sick newborn care is critical to allow scale-up and improvements to neonatal care, especially across sub-Saharan Africa, where rates of newborn deaths are highest globally.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.