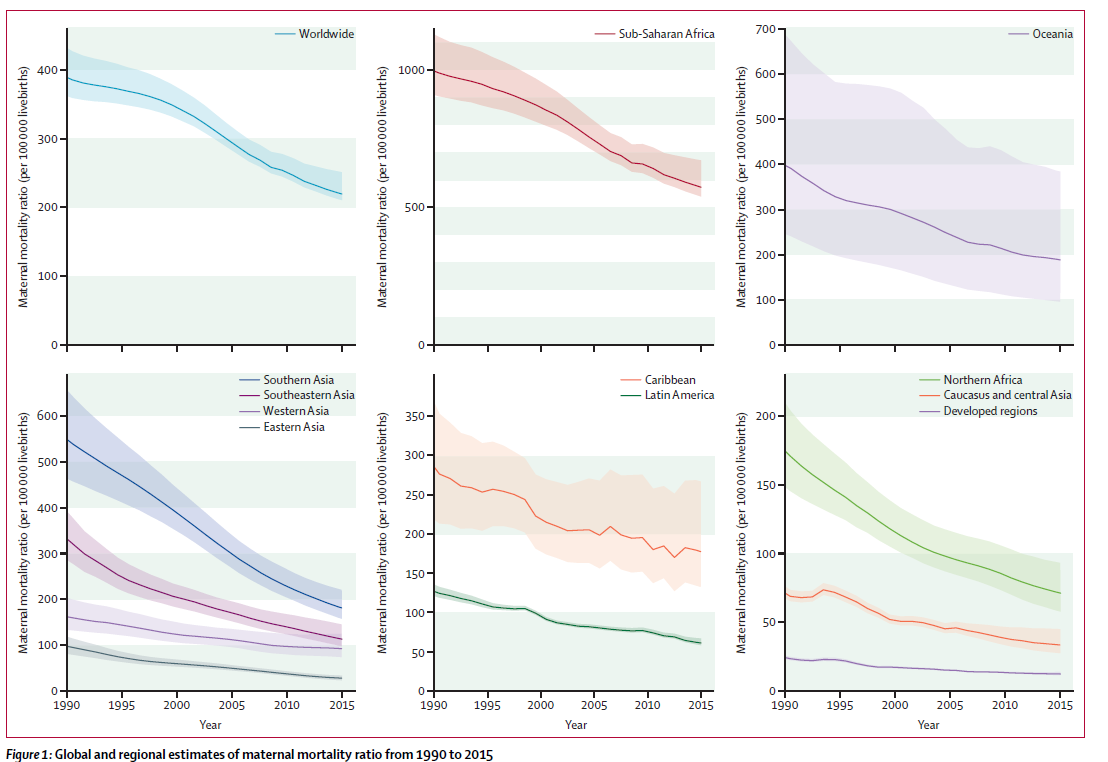

I was born and raised in the Karamoja Region, situated in North-Eastern Uganda. My country is considered a developing country, but it has been making great efforts to improve maternal and child health. Our maternal mortality ratio (MMR) has reduced from estimated 700 in the 1990s down to 336 deaths per 100,000 live births today. Despite this, we’re below the 2015 global estimates of 216 per 100,000 but much lower than the average in Sub Saharan Africa (sSA) which is about 530 per 100,000 live births. Part of the problem is that the gains we’ve achieved have either not been sustained or have been disproportionately distributed within the country.

When I was born, and up until about seven years ago, the dominant form of birth assistance was via Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs). To put this in statistical terms, in 2012, Skilled Birth Attendants (SBAs) constituted just 12% of total deliveries in the region, this figure rising to 30% a few years later. And more importantly to my story, this means one thing: my mother has never delivered under the care of an SBA – I’m not even sure if I’m fully immunised or not! But as I’ve survived so many childhood illnesses, mostly using just traditional concoctions, I’m fairly confident in saying in belong to the special group of, “immunised youth”, as our President fondly calls the youths of Uganda.

Education Against the Odds

"We studied on empty stomach and walked around barefoot. I was considered to be one of the richest kids in school, just because I wore shorts."

It was not just health services lacking in the area I was raised. Access to education was a wild-dream for many-a-child, a fact made worse by more than three decades of armed civil strife that claimed some of my former classmates. I went to school at the ripe old age of nine years’ but made such tremendous progress that I was promoted quickly. An even more remarkable achievement given that the school was 7-8km away from home, and I never missed a class unless I had a good reason such as sickness or fear of the cane. The latter was quite common at the time, and I almost gave up after one particularly nasty experience!

Our classes were mainly conducted out in the open, under trees or occasionally in the grass-thatched houses that our parents had constructed. We studied on empty stomach and walked around barefoot. I was considered to be one of the richest kids in school, just because I wore shorts. My first pair of shoes coincided with my time in the preparatory seminary – a place I probably owe everything I have ever achieved in my life. I remember writing on the floor, guarding my answers against the wind (and other students!) until the teachers could mark them.

The Patient who Changed Everything

"The look on her face is still etched in my memory. To this day, it is still the most heart-wrenching expression I have ever seen. And it made me determined to bring about change."

Quite a lot happened after this but to cut to the chase, through a combination of hard-work and sheer luck, I became the first from my clan to reach university, where I studied medicine. Upon finishing medical school, I was posted to Kalongo Hospital in Acholi Sub-Region – an area that was recovering from years of the LRA insurgency.

It was here, that as an enthusiastic and active young intern doctor, that I would meet the young patient who would be the beginning of my path to the LSHTM.

It was a rainy night and I was on call. Around midnight, I received a call from the Maternity Ward reporting an emergency. Still relatively naïve, I was soon in the ward reviewing a pale and grief-stricken 19-year-old lady who was lying on the examination table drenched in a pool of her own blood. I was lucky that we were in a missionary hospital which had most of the medical equipment needed, a rarity. Despite this, when I examined the young lady’s abdomen, she had palpable foetal parts and no sign of foetal life – we would have to do emergency surgery the dead foetus if we were to save the woman.

I called my boss while we wheeled her to the theatre, and for the next eight-hours, we sweated in theatre, working our socks dirty, trying to save her life. Sadly, during the surgery, despite saving her life we were forced to remove her uterus. A few weeks’ later after she had recovered, I was responsible for telling this young woman that she would never be able to have children.

The look on her face is still etched in my memory. To this day, it is still the most heart-wrenching expression I have ever seen. And it made me determined to bring about change.

And change is possible. To explain and get to the bottom of this case – this young 19-year old lady had laboured at home for three days before coming to us. Her mother-in-law had refused to bring her to the hospital because of a previous experience where a similar situation had occurred and the baby was distressed and had to be delivered by emergency C-Section. Sadly, the baby died a few days later, and the mother-in-law believed this only happened because of hospital delivery and would never allow this to happen again.

Because of this, my 19-year old patient’s pleas that she was dying and for help fell on deaf ears. She only came to the hospital once the severity of the situation became apparent that they delivered her to hospital by motorcycle ambulance. They dropped her at the hospital and sped off. During recuperation at the hospital, none of them visited her – not even her husband!

Uncovering the Root-Cause

"I can’t overstate the fact that health facilities really grapple with under-staffing and lack of critical health workforce in Karamoja."

Sadly, this is not an isolated case. It’s very wide-spread and the society I come from is particularly conservative, where SBA is frowned upon and women who deliver in health facilities are considered to be “weaklings” or not, “woman enough”. However, the problem stems from a health care system which was poorly designed for the Karimojong women, they feel that standard doctors abuse or expose their privacy and don’t preserve their dignity. This sentiment was exploited by the TBAs.

I’m pleased to report that this narrative has been changing for the past few years, thanks in part to the birth cushion; an innovation of UNICEF and Doctors with Africa, CUAMM. It’s a simple delivery coach that simulates the traditional squatting position of the among the Karimojong women. In fact, the period after introduction of the birth cushion witnessed an unprecedented surge in facility-based deliveries among the health facilities that implemented them.

However, this hasn’t fixed the problems.

I can’t overstate the fact that health facilities really grapple with under-staffing and lack of critical health workforce in Karamoja. For example, while working in Kotido Health Centre IV as a medical officer (medical doctor) after I had finished the internship, I used to carry out emergency Caesarean Sections without an anesthetist – I trained myself to administer spinal anesthesia and a midwife or theatre attendant would monitor the mother whilst I continued the surgery.

Because of this, TBAs continue to lure mothers away from facilities by making them feel comfortable and valued. Something that can’t be replicated with one or two overworked midwives covering more than 100 deliveries, as well as postnatal, antenatal, immunisation and ART clinics per month. And the equipment and essential medicines aren’t always available, so some mother’s walk 40km only to be referred to one 100km away. It’s a big ask for the facilities to match the TBAs in good communications and respect.

Making the Difference: Life at LSHTM

"The school has been my home for the past seven months, and it has given more than I could ever have imagined and helped dispel some of my pre-arrival worries."

In a nutshell, these stories and experiences played a big role in my next career step: a decision to study Public Health at The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. I was eager to deepen my understanding of current issues affecting LMICs. I wanted to develop the essential skills and knowledge to design innovative, evidence based, cost-effective, context-appropriate, and culturally-acceptable interventions to tackle these issues.

So nearly six-years after graduation, I would become the first ever (known) Karimojong to be awarded the Chevening Scholarship to study at LSHTM. Although I’m not the first Karimojong to study at the school – my former boss is a 1998/1999 LSHTM alumni.

The school has been my home for the past seven months, and it has given more than I could ever have imagined helped dispel some of my pre-arrival worries. I have made loads of friends, the course directors are really friendly, and I want to express a lot of gratitude to my course supervisor, Dr Veronique.

I am convinced that I am now fully equipped, like a warrior before a decisive battle, to address the challenges I outlined previously. For instance – a lot of public health interventions could have averted the outcome for the young lady I treated. A policy of health education and family planning after the first delivery could have been more appropriate. Or could the hospital have taken the time to speak to the young family in a respectful manner and educate them about what exactly went wrong and what could be done to prevent it in future?

"I am convinced that I am now fully equipped, like a warrior before a decisive battle, to address the challenges I outlined previously."

I’m fully aware that it will be an uphill battle task. But it’s not an insurmountable one. With the current technological advances and improvement in SBAs, I see no reason why we should not dare to dream!

LSHTM's short courses provide opportunities to study specialised topics across a broad range of public and global health fields. From AMR to vaccines, travel medicine to clinical trials, and modelling to malaria, refresh your skills and join one of our short courses today.