“For me, education was power” – Michelle Obama

For International Day of Education, we're exploring the role schools play in public health and their importance towards achieving the SDG targets.

More adolescents, more time in school

When it comes to formal education, schools are a vital resource. Defined as, ‘learning spaces and learning environments for the teaching of students under the direction of teachers’, schools are not a new concept. Evidence of formal schools has been found among many ancient cultures including ancient Greece, ancient Rome, ancient India, and ancient China.

That being said, until relatively recently, many parts of the world only had formal education up until children reached adolescence (age 10). But times are changing. Right now, we’re facing one of the largest adolescent populations in human history, a quarter of the world’s population – or 1.8billion people – are aged between 10 and 24.

And more of them than ever are in school.

In the past 35 years, there’s been a staggering increase in adolescents enrolled in secondary schools from 47% to 76%. In addition, the education gender gap is also closing, with more young women getting a secondary education than ever.

Fantastic progress towards achieving SDG 4 (combining health interventions in schools with inclusive and equitable education for all) – but is this bulging population of adolescents within the school environment helping or hindering progress towards the other SDGs? That all depends on what they’re learning.

Schools and health – where’s the crossover?

As most people who’ve been through the school system might be aware, schools don’t always represent a ‘safe harbour’ for adolescents, and education comes at a price for many. UNICEF estimates that rough 150 million 13-15 year olds worldwide have experienced peer-to-peer violence in and around school. More than a third have been bullied in the past month, and a third have been involved in a fight.

What should be a nurturing environment to stimulate learning can instead be a perfect ecosystem for physical, verbal, and sexual violence to manifest and thrive. Not the kind of lesson young people should be having.

With the world’s public health agenda shifting its attention towards non-communicable diseases, there’s important questions to be asked about the role of education and schooling as a primary prevention strategy. NCD’s are responsible for 63% of deaths worldwide, and most risk factors begin in the adolescent period. This unique, confusing, and vulnerable time for young people is spent establishing behavioural and social norms within peer groups – mostly through school. With that in mind, it’s important that the right ecosystems and health behaviours are established within schools.

MARCH researchers are currently working on this, and below are just three examples of ways they’re blending schools systems with health systems to:

1. Keep girls in school and change attitudes to periods.

2. Improve overall health outcomes by altering an entire school ecosystem.

3. Prevent dating and relationship violence.

1. Keeping girls in school. Period.

The gender gap may be decreasing in education but there’s still a way to go. A key barriers to girls attending and succeeding in school in some settings is management of menstruation. Managing periods can be tough even in the best of circumstances, and this becomes even trickier when there’s lack of knowledge about menstruation, lack of private and safe toilet facilities at school, lack of guidance on effective pain management and financial problems in buying pads.

Even more horrifying is the exploitation that can go hand in hand with this. For some young women, access to the materials to help manage their periods (and therefore stay in school), has become a way for men to sexually exploit them. As Michelle Obama famously quotes, education represents power, but that power has a price that’s far too high for too many girls. Quality research and effective interventions are needed to ensure every girl and woman can feel in empowered and in control when it comes to managing their period.

The MENISCUS (Menstrual health interventions and School attendance among young Ugandans) studies aim to build a strong evidence base on the impact of, and best practice in, good menstrual management in schools. This evidence can then be used to inform policies and resource allocation – making this area a priority.

So how exactly does this evidence base get built?

First things first, in the MENISCUS-1 study, the team needed to understand how young girls in Uganda managed their periods, the barriers and facilitators of good management, and assess the impact of periods on school attendance. This scoping exercise revealed that poverty and menstruation were the primary reasons why young women missed school – with 20% reporting that they’d missed a day of school in the previous month because of a period. The stats lay it bare: 25% of the young women surveyed couldn’t afford sanitary pads, and 77% reported pain.

Next, using the insight gathered, the team, together with relevant stakeholders from the Ministries of Health and Education, designed a five-part intervention package to address the key barriers. This was implemented and evaluated in two secondary schools in the Meniscus-2 study, to find out if it works, is easy to implement, sustainable, and acceptable.

The results were very promising. There was strong evidence that the intervention improved girls’ knowledge of menstruation, benefitted from the drama skit, and increased their use of appropriate materials. Some of the most notable improvements were observed with pain relief (92% of girls reported using successful pain relief methods by the end of the study) and WASH facilities (86% said the facilities were better than they had been, and 95% of those said the changes made it easier to manage their period).

Back to the original question – did it keep girls in school? Simply put, it would appear so. The association between absence and menstruation decreased after the intervention. Overall, the results suggest that this package has the potential to substantially increase girls’ education, health, and wellbeing. However, this was a small scale pilot study without a comparison group of schools, and the next stage of MENISCUS studies involves a rigorous evaluation of the intervention in 48 secondary schools in Uganda. If funded, this will also measure an exam performance and will be one of the first studies in a LMIC to evaluate the impact of a health-focused intervention on educational outcomes.

You can read more about MENISCUS here.

2. Staging an intervention at the whole school level

Schools are more than bricks and mortar, they are a habitat where teachers, parents, and students gather with an interest in a common resource – education. With such a complex ecosystem, the question that begs to be asked is: will changing the whole system be more effective than targeting an individual within that system?

Where there’s important questions to be asked, researchers will answer. Two recent studies have looked at the effect of whole school interventions on health outcomes. Although varying significantly in their settings, one high income and one low income, results from both studies indicate one unified message: yes, whole school interventions work.

You can read more on both of them here. But for now, a focus on the SEHER trial.

The SEHER trial was conducted in 74 government-run schools in the state of Bihar, India. The intervention involved activities at multiple levels (whole school, group, and individual), all feeding into one another with the aim of finding out if the whole school environment could be improved, and whether attitudes to particular health behaviours could be improved.

The whole school activities were based around a ‘theme of the month’ and included the formation of health promotion committees/health policies (with stakeholders at all levels –staff, students, and parents), a speak-out box for anonymous complaints and suggestions, and creative activities such as a monthly magazine and competition. Group activities included workshops and elected peer groups to represent the student voices in whole school activities (e.g.running the competitions and discussing issues raised in the speak-out box). Finally, the individual activity involved problem-solving counselling or referral to specialists for anyone needing extra support.

Of note, part of the SEHER trial was testing whether a lay-counsellor or teacher trained to deliver the intervention was more effective. Making three study conditions – intervention led by lay counsellors, intervention led by teachers, and no intervention.

And the results were heartening. In schools with lay counsellors delivering the intervention, the overall school climate significantly improved. In addition, there were reductions in bullying, violence, symptoms of depression, and smoking as well as improved sexual health knowledge and attitudes towards gender equity. These improvements weren’t seen in the schools without the intervention, or schools where the interventions were led by teachers.

Based on the results, the trial noted four key priority areas for effective change moving forward:

- Promoting social skills among adolescents.

- Engaging the school community (i.e. adolescents, teachers, and parents) in school-level decision-making processes.

- Providing access to factual knowledge about health and risk behaviours to the school community.

- Enhancing problem-solving skills among adolescents.

You can read more about the SEHER trial here.

3. Relationship education – does it start at school?

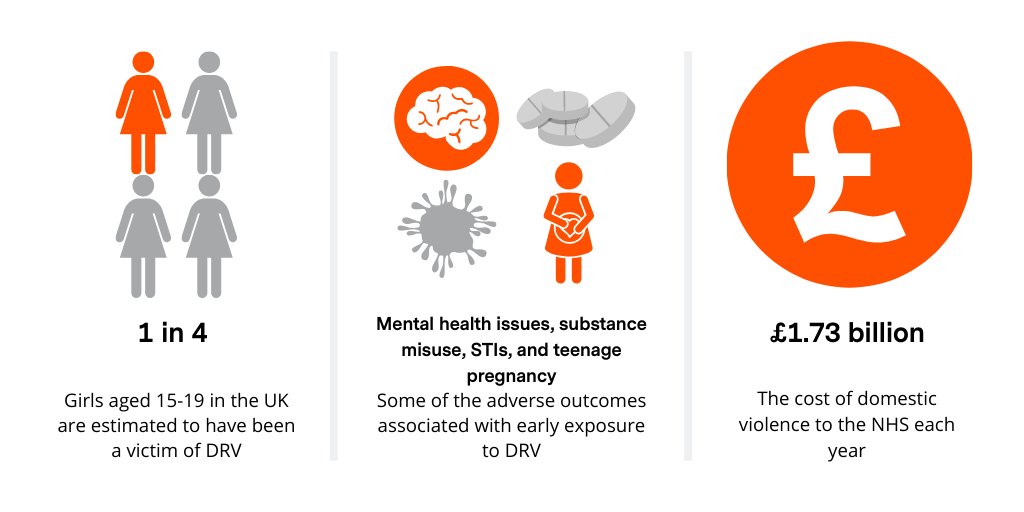

Dating and relationship violence (DRV) includes threats, emotional abuse, controlling behaviours, physical violence, and coerced, non-consensual or abusive sexual activities perpetrated by a partner.

Worryingly, the stats paint a pretty bleak picture for how common this type of violence is experienced among adolescents. In England, as many as 48% of girls and 27% of boys aged between 14-17 who’ve had intimate relationships have experienced DRV.

Early experience of DRV can have long lasting negative health outcomes for the people affected, including sexually transmitted infections, adolescent pregnancy, and mental health issues. Importantly, it also correlated with poor educational outcomes. Despite this, up until recently, no randomised control trials had ever been done in the UK to try and prevent it.

Dating behaviours begin in early adolescence, making this a crucial time for interventions. If effective prevention strategies can be established at this time, it could stop DRV becoming a behavioural norm, representing an opportunity for long-lasting positive health and educational outcomes for future generations.

DRV arises from individual anger management and communications deficits, but it also relies upon, and thrives in particular environments. Within the school eco-system, young people begin their socialisation into gender norms, often a negative and sexist experience. Adolescents spend their daytimes in an environment where gender-based harassment and DRV remains unchallenged, and may even be widespread. At a time where social survival pressures are at their highest, it’s understandable that young people don’t necessarily intervene when they see DRV because of the fear of repercussions.

So how can we intervene?

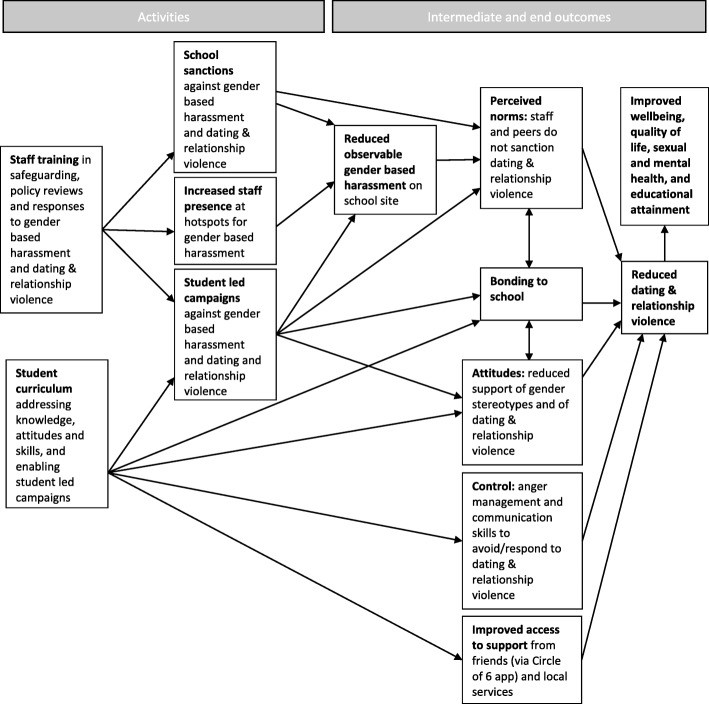

By changing the whole-school ecology. A feat which can only be achieved with a multi-pronged approach – something MARCH based researchers have been testing with Project Respect. Based upon two previous US studies, Safe Dates and Shifting Boundaries, Project Respect drew from these interventions and worked with students and staff in UK secondary schools to refine the programme to suit UK audiences.

Safe Dates delivered a 10-session curriculum on the consequences of DRV, gender roles, conflict management skills, norms, help-seeking, and student participation in drama and poster activities. Evidence into this intervention showed a significant reduction in DRV. Shifting Boundaries explored a more intensive intervention, comparing curriculum-only, environmental shifts, or a combination approach. The environmental shift involved students mapping the hotspots for increased gender-based harassment, and staff having an increased presence there, as well as increased sanctions for perpetrators such as building-specific restraining orders.

Whereas Safe Dates showed success with a curriculum-only intervention, Shifting Boundaries indicated that the environmental element was vital for changing behaviours.

For Project Respect, researchers took those learnings and worked closely with stakeholders such as the NSPCC and the Advice Leading to Public Health Action young researchers’ group to develop a package for 13–15 year olds. Once optimised, they piloted the intervention in schools in the South of England.

At these early stages, the research was focussed on the feasibility of Project Respect in UK schools, and the process of implementation. Using qualitative methods, they were exploring if/how the programme should be improved and how contextual factors (eg. what else is going on in the school, and characteristics of the students) affect how the programme is delivered and received, as well as its mechanisms of change.

The theory goes that by training staff and students, and implementing real change, students will be given the individual and environmental toolkits they need to reduce negative gender stereotypes, speak out against violence, feel more bonded and accountable to the school environment. Ultimately leading to reduced dating and relationship violence and overall improvements in wellbeing.

The results of the project are currently being analysed and are due in the next few months. But if they show that Project Respect is feasible and once the protocol is in its optimal form, larger scale studies will test whether this intervention is effective in reducing DRV and improving wellbeing.

You can find out more about Project Respect here.

Changing outcomes for a whole generation

Arguably, education and the learning it enables as humanity’s greatest renewable resource. The ability to harness and utilise knowledge should be a fundamental right for everyone, but alongside this comes the right for all adolescents to have a safe and healthy space to access that learning.

Based on current evidence, the future involves embedding school-based health interventions as part of the agenda to ensure inclusive and equitable education for all. If we can achieve this for the 1.8 billion adolescents today, we can change health outcomes for a whole generation of people tomorrow, bringing all SDG targets one step closer.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.