Bacterial meningitis is a major public health concern with more than 2.5 million cases estimated to occur every year, according to the Meningitis Research Foundation. Developing affordable vaccines that provide broad coverage against meningococcal disease strains is a key part of the World Health Organization’s roadmap to defeating meningitis by 2030.

Can you tell us about your work developing a vaccine to protect against meningitis?

I work on Streptococcus pneumoniae, one of the leading causes of both bacterial meningitis and pneumonia. The Serotype 1 strain is a particular problem in the so-called “meningitis belt” in sub-Saharan Africa, stretching from Senegal into western Ethiopia. Here, dry winds from the desert carry dust and cause small abrasions in the back of peoples’ nose and throat. This allows the bacteria a path to get to the ‘meninges’ - the layers surrounding the brain and central nervous system, which can lead to inflammation and cause meningitis.

Why do we need new vaccines in addition to those already available?

Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance has made phenomenal progress in reducing meningitis in the “meningitis belt” using vaccines against Haemophilus influenzae B (Hib), Neisseria meningitidis type A (MenAfriVac), and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines (PCV). All these vaccines have good heat stability, making distribution to remote areas much easier as there is no need for a strict cold chain of refrigeration.

All three of these vaccines are glycoconjugates. These vaccines work by binding a complex sugar (glycan) from the outer surface of the bacteria to a protein that generates a good immune response like tetanus or diphtheria vaccine. The more complex the vaccine is, the more costly it is to produce. Hib and MenAfriVac both contain just a single bacterial sugar, while PCV contains multiple. To make these vaccines, a large volume of the infectious bacteria is grown, and the sugars chemically extracted. These are then attached by complex chemistry onto the vaccine protein. This process requires a lot of quality control steps to get consistent batches, adding to the costs. Gavi has worked with vaccine suppliers to reduce costs as much as possible; PCV10 is now produced in India at a cost of $3 per dose compared with $50-100 per dose in high-income countries. In comparison, a non-glycoconjugate vaccine such as Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) can be as low as $0.30 through Gavi.

How is the vaccine you are working on different, and can it be made more affordable?

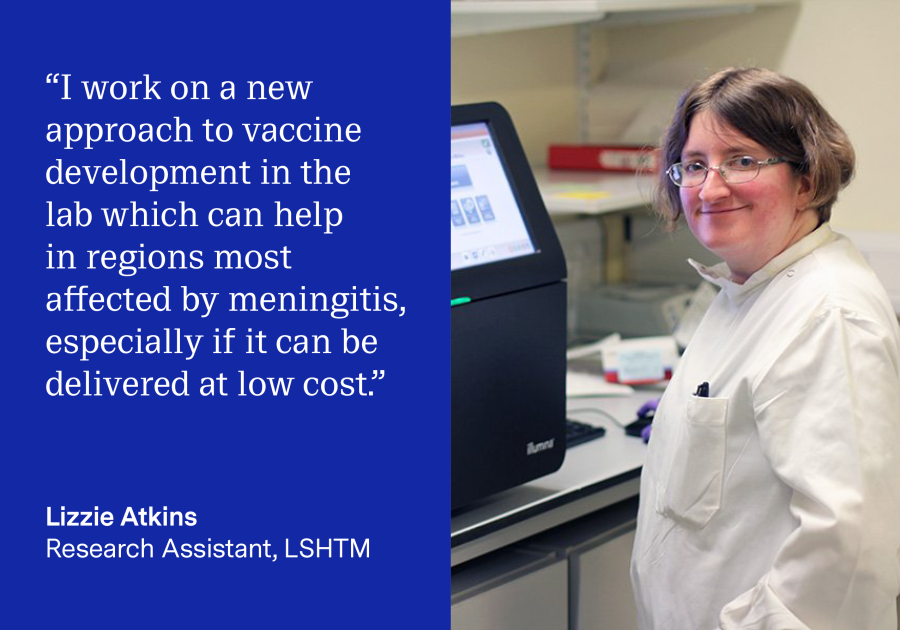

Despite the success of the existing vaccines, they have not been equally effective. Serotype 1 pneumococcal disease is still a problem in the ‘meningitis belt’ despite being targeted by PCV. A monovalent, single serotype vaccine might be able to help in this region, especially if it can be delivered at low cost. I am working on a new approach to vaccine development in the lab. My work is focused on producing the complex bacterial sugar in a laboratory strain of E. coli, which is much safer to work with compared to the infectious bacteria used in the production of PCV. I then use bacterial enzymes to replace all the expensive chemical processes to attach the sugar to a protein to produce the vaccine. By turning E. coli into tiny vaccine factories, all we then have to do is extract and purify the vaccine. We are currently making a small amount of our desired product and need to increase it for production to be viable. Most of my current work is focused on making small changes in the bacteria and the growth conditions to see if they improve the quantity of vaccine we produce.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to build a career in global health, we offer a range of MSc programmes covering health and data, infectious and tropical diseases, population health, and public health and policy.

Available on campus or online, including flexible study that works around your work and home life, be part of a global community at the UK's no.1 public health university.