EU and UK flags. Credit: Dave Kellam / Flickr

“Our commitment to Europe is rooted in our shared values in addressing social injustice and in finding solutions to our most pressing health challenges. I see myself as a global citizen leading a global institution and this will remain the case beyond Brexit. We will continue to place great value on our work with, in and on Europe. In this feature we highlight a small selection of our European research, staff and student stories which I hope will give you an insight into this important aspect of our work.”

Professor Baron Peter Piot, Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Maintaining our links with European partners

Our work is focused on improving public health in the UK and around the world. The problems we set out to solve are complex multifaceted issues, rarely limited to one country, which need to draw together a wide range of expertise and capabilities.

We have been fortunate to be part of a group of 28 countries all facing similar challenges – including road traffic injuries, cancer, mental illness, and heart disease among others. Many of these countries have adopted different responses, backed by huge stores of data, allowing us incredible levels of insight into the success of different health interventions, and endless lessons for those wanting to improve health services. Access to these data has allowed for a huge amount of comparative research, assessing different health systems and identifying room for improvement in our own. A striking example is the EUROCARE programme – running since 1989 – which brought together EU cancer registries and showed that cancer survival in the UK was significantly lower than in many other EU countries. This discovery led to the NHS Cancer Plan for England and a subsequent improvement in cancer survival. The CONCORD programme – running at the School since 1999 and profiled in more detail later - has now established surveillance of cancer survival trends in more than 70 countries world-wide, including 30 European countries.

Collaborations and funding from the European Union have also made research possible which has addressed critical health, economic and social problems, from developing Ebola vaccines to minimising the health impact of populations fleeing war zones.

These cross border issues are challenging and often combine many different areas of expertise and in many cases, these projects involve vulnerable people and isolated communities, so require careful management and communication, themselves highly valuable skills.

Such projects would be impossible for one institution to handle. The model of centralised funding for collaborations between a diverse range of partners – as well as simple data sharing rules and unified regulation on issues such as clinical trials - has allowed us to work at our best, and collaboratively produce health outcomes that are more than the sum of their parts.

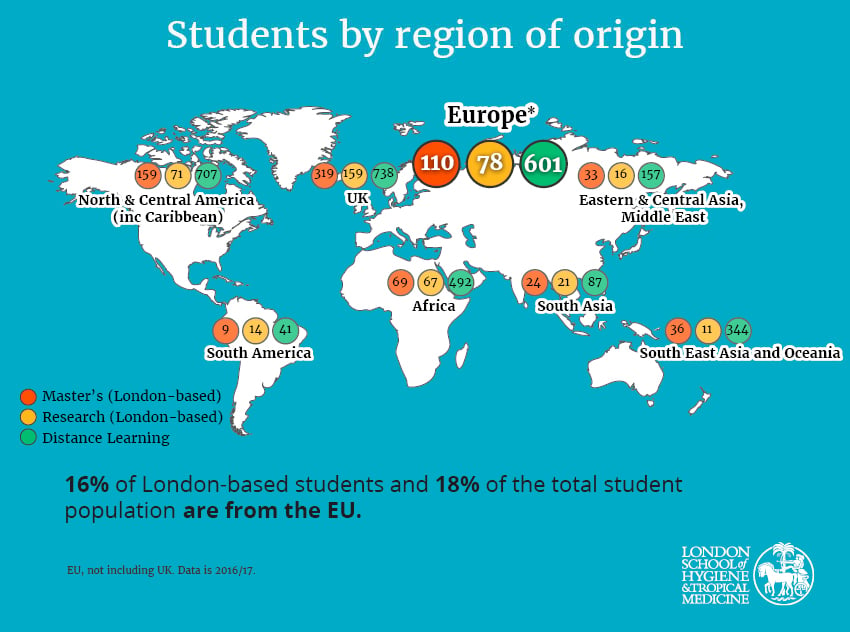

Finally, we are able to contribute effectively to these projects because of the quality of staff and students we attract, and because we nurture them through their careers. We can recruit from a pool of excellent researchers who graduate from top academic institutions across Europe. But we also nurture many great students through the School. These students are drawn to us because of the quality of our teaching – all the world leading experts within the School teach - and many choose to stay and pursue careers with us. We also benefit greatly from exchanges of students and researchers through the Erasmus and Marie Curie research programmes, which allow dynamic sharing of ideas to explore new areas and challenge ourselves.

Recruiting from outside the EU can be an administrative challenge but wherever possible we work to ensure the best researchers can bring their expertise to the School, regardless of where they are from, and will continue to do so even as the United Kingdom’s place in Europe is reset.

As the UK seeks to negotiate a new relationship with the EU, uncertainty - about future collaboration and about the attractiveness of the UK to researchers and students - is inevitable. But we have become adept over the years at participating in and running European collaborative projects and we have a lot more to give. We will do everything we can to ensure that the School continues to participate in health research and influence health policy for the better in Europe and globally. We will continue to nurture staff from all countries through their careers and provide a fantastic environment for the world’s best health researchers.

As the world reshapes itself, we will remain an open international institution committed to collaborating to improve health around the world. We’d like to take this opportunity to share some stories of how our work with other parts of Europe and with our European friends has made the world a healthier, happier place.

“The School has a rich history of engagement with European institutions and collaborators. Our international staff and students lead and support collaborations that improve health systems across Europe. With European partners, we tackle the world’s most pressing health problems. As the United Kingdom’s political relationship with the continent changes, we celebrate our work in Europe, and with Europeans, and we remind ourselves that while people may sometimes be limited by borders, illness and disease are not. Whatever the future holds, improving the world’s health will continue to require a commitment to working across borders.”

Professor Martin McKee, CBE

Professor of European Public Health, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Immediate Past President, European Public Health Association

Research case studies

- Europe collaborating for Europe: Mental Health interventions for refugees

- Europe collaborating for Africa: Developing an Ebola vaccine

-

The School is working with European and African partners to develop an Ebola vaccine, in the hope of avoiding another devastating outbreak that could cost thousands of lives.

Collaborative projects led by the School are hoping to license an effective vaccine for Ebola, potentially avoiding a repeat of the 2014 West Africa Ebola outbreak, which killed over 10,000 people.

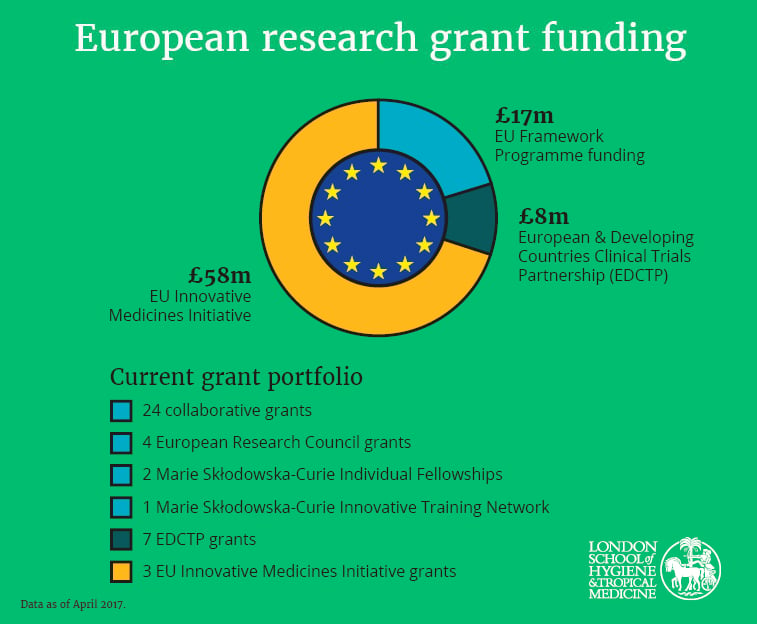

The School is leading the EBOVAC and EBODAC projects, backed by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), a Public Private Partnership jointly funded by the European Union and the European pharmaceutical industry.

EBOVAC is carrying out Phase 1 and 2B trials in Europe and Sierra Leone to understand the immune response to the vaccine and vaccine safety, with a view to gathering data to license it. EBODAC is providing the community support to ensure these trials – which are mostly being conducted among communities unfamiliar with medical research – are carried out effectively, making sure those who take part understand the trial, and make free and informed decisions.

The projects bring together pharmaceutical, healthcare and community relations expertise from business and academia across Europe, as well as charitable foundations in the USA and Africa. The vaccine under investigation was developed by Janssen, a Belgian pharmaceutical company.

Dr Elizabeth Smout, Research Fellow & Community Engagement Coordinator for the project from January 2015 – August 2017, said: “It’s a privilege to work on a project that could genuinely prevent another life threatening disaster. Such projects are only possible thanks to our ability to bring together such a broad range of expertise in both research and community engagement to make everything work.

“Being a member of the EU automatically opens the door to a lot of funding opportunities, and the School has become experienced in applying for these grants and leading these projects. The changes ahead do add a lot of uncertainty to the future of this and other projects. If we are less able to participate, our partners lose out on our expertise, our researchers lose out on funding, and the potential of the projects – on which people’s lives depend - is diminished. Naturally everyone is concerned about the future but we are also hopeful that a deal can be reached that allows us to continue to play our part in such world leading research funded by Europe.”

- Europe collaborating for Africa: Reducing deaths from HIV-related meningitis in Africa

-

Another European Union-funded project focused on Africa is AMBITION, a new clinical trial being led by the School which aims to tackle the high number of deaths caused by HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis (CM), a severe fungal infection of the brain that occurs in patients with advanced HIV infection.

AMBITION hopes to identify a new very clinically-effective and cost-effective treatment for CM using very high single doses of the drug Liposomal Amphotericin B (Ambisome). The project will recruit 850 patients across six African sites, making it the largest ever CM trial.

Early mortality in HIV programmes in Africa is considerably greater than in high-income countries and almost 20% of deaths are directly attributable to CM. It is estimated that roughly 180,000 people die from CM each year around the globe, with approximately 75% of these deaths occurring in sub-Saharan Africa.

The principal funder for the €10m (£9m) AMBITION-cm Phase III project is the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), and the trial is being conducted with partners across Europe and Africa.

- Improving health across Europe: Reducing infectious diseases through better vaccine information

-

Misinformation about the safety of vaccines can dramatically affect vaccination programme coverage, leading to avoidable outbreaks of infectious diseases. The School is helping design more effective information campaigns across different countries to help people make more informed decisions.

Vaccines are one of the most effective measures in preventing disease outbreaks and childhood mortality, saving some two to three million lives worldwide every year.

All available vaccines go through rigorous tests to ensure they are safe and effective. Yet many people worry about their safety, sometimes based on misinformation about their side effects, leading them to hesitate or refuse vaccination. When groups of unvaccinated people live close together, infectious diseases can spread quickly.

The ADVANCE project, funded by the EC through the Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI), is addressing vaccines’ risks and benefits across Europe. As part of the ADVANCE project, the Vaccine Confidence Project has conducted research to understand vaccine risk perceptions and is developing communication strategies to build confidence in vaccines.

The ADVANCE project brings together vaccine databases from across Europe, as well as demographic data for statistical analysis. With this data, researchers can assess different population needs, learn which systems are working best, and understand what factors contribute to acceptance or rejection of vaccines. This can be combined with studies of how information spreads online, in the media, and through communities.

Confidence in vaccination can vary considerably between and within countries. In a 2016 67-country survey, France was found to be the country with the least confidence in the safety of vaccines, with 45% of respondents not agreeing with the statement “vaccines are safe”. This could be explained by the historical context of France, which has faced multiple public health challenges linked to distrust of health interventions. Some concerns can also spread from one country to another, as in the case of rumours and safety concerns about the HPV vaccination which are rapidly shared across countries through social media and the internet. In France, HPV vaccination coverage has dropped from over 25% in 2012 to 14% in 2015 due to public distrust.

“This is why the pan-European perspective is vitally important to such research,” says Emilie Karafillakis, a Research Fellow at the School. “It allows us to study different countries, make comparisons, and learn from each other. The team here is well placed for such work, since our researchers bring together expertise developed in different health systems, as well as a range of European languages, all of which is instrumental in assessing how information spreads in different communities.

“Such research helps improve vaccine coverage in countries with problems, but it will also help countries that currently have high vaccination coverage to be prepared. Just like infectious diseases, rumours do not stop at borders, so it’s important to develop consistent well-informed plans to respond to changes when they happen unexpectedly.”

- Improving health across Europe: Developing new diagnostic tools for infections

-

European researchers are developing simple tests to quickly identify different infections; and evaluating the most effective ways to introduce such tests to different health systems.

The European Union-funded project, PERFORM, is developing new diagnostic tests to distinguish reliably between bacterial and viral infections in children with fever.

The five year project aims to identify new biomarkers – molecules in bodily fluids which indicate particular infections. Once identified, tests can be developed to spot which biomarkers are present, giving clarity on the type of infection. Improving diagnosis in this way will help identify those who need antibiotics, and reduce ‘just in case’ prescriptions which are contributing to growing antibiotic resistance.

As part of this project, the School is conducting an evaluation of costs and impacts of introducing the tests in different European health systems. A major part of this research involves interviewing parents and medical practitioners across Europe to understand how to roll out the new diagnostic tools most effectively.

The project brings together medical and health economics researchers, as well as public and commercial labs, from 10 European countries - Latvia, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Netherlands, Spain, Slovenia, France, Greece, UK - alongside partners in The Gambia and Nepal.

Dr Shunmay Yeung, Associate Professor in Tropical Medicine at the School, explains: “The collaboration with so many partners across Europe is hugely valuable. It gives us access to a wide range of expertise and research instruments which improve our chances of identifying relevant biomarkers, and a wider pool of recruits to help us validate them, but it also allows us to evaluate how different health systems use diagnostics tests.

“Evaluating different health systems as we develop the tools helps us find the best strategies for rolling them out. Antibiotic resistance is a global issue, so the more widespread the reduction in unnecessary use, the better for everyone.”

“We learn a lot from working with each other, helping us understand the strengths and weaknesses of our own healthcare systems, which can feed into improved approaches. Equally, other partners have a huge amount to learn from the UK’s approach; the UK’s cost benefit system of evaluating medical interventions, run through NICE, is looked to by many as a model. Through the School, this considerable UK expertise can feed into the project, some or all of which would be lost if we could not take part on equal terms. We gain, but we also share, it’s an effective model.”

- Research in and beyond the EU: monitoring global trends in cancer survival

-

The CONCORD programme analyses global trends and international differences in cancer survival. With a database of over 30 million cancer patients from more than 300 cancer registries in over 70 countries, it has become a vital tool to assess the overall effectiveness of national healthcare systems in dealing with cancer.

The results help to inform cancer policy on wider access to early diagnosis, screening and optimal treatment, in order to improve cancer survival.

CONCORD has helped to underpin national and international cancer control policies in the EU and beyond. The rigorous quality control procedures applied to the data submitted to CONCORD have also led to improvements in data collection and quality control in cancer registries all over the world.

From 2017, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) will include survival estimates from the CONCORD programme for more than 50 countries in its print and online publications Health at a Glance. This reflects recognition by an international organisation of the global coverage, methodological rigour and international comparability of the CONCORD survival estimates.

The European Union will also use survival estimates from the CONCORD programmes in the Country Health Profiles now being prepared for the 28 EU member States as part of the new State of Health in the EU initiative. Twenty-six of the 28 countries are involved, all of which share data and expertise, and all of which benefit from the results.

The CONCORD programme is endorsed by many international organisations including WHO, OECD and the World Bank.

The School is well placed as the home of the CONCORD programme. The UK’s membership of the European Union for more than 40 years has facilitated the sharing of data under EU directives and regulations. London still attracts many of the world’s best health researchers, allowing top teams to be assembled.

However, there is serious concern that this research leadership will be compromised when the UK leaves the EU. Dr Michel Coleman, Professor of Epidemiology and Vital Statistics at the School, and co-Principal investigator of the CONCORD Programme, says: “The School’s hard-won expertise in leading international projects will be rapidly eroded if fewer EU-funded projects can be coordinated here after Brexit. Researchers in other EU countries are much more likely to take the lead in multi-centre EU-funded collaborations. The School’s ability to deliver such international research programmes will also be seriously undermined if the many EU nationals who currently work on these programmes decide to leave. That is already happening in the National Health Service, and the government has so far failed to provide any reassurance that the rights of EU nationals will be protected after Brexit.”

Dr Claudia Allemani, Associate Professor in Cancer Epidemiology, also co-Principal Investigator of the CONCORD Programme, adds: “International research programmes such as CONCORD offer hope for the School’s future on the international stage. CONCORD is one of many such programmes that have shown how international collaboration between EU and non-EU partners can be very effective. The School is a respected institution with a history of global leadership on health issues. This heritage should ensure that the School can continue to attract the talent and funding for international projects to tackle global health problems.”

- Major study in intimate partner violence: ERC Starting Grant

-

Dr Heidi Stöckl, Associate Professor in Social Epidemiology at the School, is to lead the largest ever longitudinal study of intimate partner violence conducted in a low and middle-income country in collaboration with Dr Gerry Mshana from the Mwanza Intervention Trials Unit after being awarded a £1.3 million grant from the European Research Council (ERC).

The study of 1,200 Tanzanian women aims to shed light on the main indicators of intimate partner violence (IPV) which will shape future programmes that will improve the lives of women around the world.

ERC Starting Grants are awarded to researchers with 2-7 years of experience since completion of their PhD who also have a scientific track record of great promise and an excellent research proposal.

Previous research has identified three key risk factors for IPV: alcohol abuse; indicators of women’s economic status; and poor mental health of either partner. By following the 1,200 women for five years this study will provide high quality information on the changes over time relating to these risk factors, which will be vital to designing future intervention studies.

What does this funding mean to you?

The funding means a lot to me. On one level it is an amazing achievement for the field of gender-based violence research that a highly respected and influential research funding body like the European Research Council acknowledges that intimate partner violence is a major global public health and human rights issue and that rigorous research is necessary to prevent and address it. On a personal level, the ERC Starting Grant is a very reputable grant that is known beyond the UK and therefore presents an important milestone for my future academic career as well as many opportunities.

How important are ERC starting grants to enable research like yours to move forward?

The level of funding provided in addition to the five years duration of the grant is one of its key assets as it allows conducting more in-depth research over a longer timeframe. This is important as it generates far more meaningful data, allows cross-learning with other projects and – as in the case of this grant – provides me the time and space for developing and testing new theories.

Our people

Profiles

An Italian in London: Why the UK attracts the world’s top researchers

Dr Giulia Greco is one of the School’s health economists. After completing a bachelor in economics in her home country, Italy, she went on to study health policy at the LSE. In 2007 she received a fully-funded award from the Medical Research Council to carry out her PhD, and has remained with the School since.

She talks to us about why she was drawn to London and the contribution she has been able to make thanks to the funding and supportive networks.

Tell us about your research.

I’m currently developing a new measure to assess the impact of health interventions on wellbeing for women. Right now such assessments consider simple outcome measures such as whether someone lives or dies. We want to add more multidisciplinary measures that give a much more robust assessment.

This is much needed by governments, charities and NGOs who need to understand where their programmes and investments are most effective, and it will also help assess much broader global programmes, such as those which support the Sustainable Development Goals.

The project is being carried out in Uganda and has a particular focus on impacts in developing countries. But national agencies – such as NICE and Public Health England - are also extremely interested, as there is growing recognition that the current outcome measures are not the best way to allocate spending resources.

How is your work funded?

There are not actually many health economists in the world, so we are quite in demand. The UK has some of the leading research institutions in both health and economics so was an excellent place to progress my career, and being part of the School has helped me build networks and access funding.

Because of the competition it’s hard to recruit health economists at a higher level, so the School tries to nurture staff up through the ranks. It has been a very supportive environment, which has been a big incentive for me. Even though I spend a lot of my time in Uganda at the moment, I have a lot of support from the London team.

Equally, my research has attracted external funding which pays salaries and overheads, so I gather the School is also keen to keep me on board.

What drew you to London?

There are not actually many health economists in the world, so we are quite in demand. The UK has some of the leading research institutions in both health and economics so was an excellent place to progress my career, and being part of the School has helped me build networks and access funding.

Because of the competition it’s hard to recruit health economists at a higher level, so the School tries to nurture staff up through the ranks. It has been a very supportive environment, which has been a big incentive for me. Even though I spend a lot of my time in Uganda at the moment, I have a lot of support from the London team.

Equally, my research has attracted external funding which pays salaries and overheads, so I gather the School is also keen to keep me on board.

Do you worry about what the future will bring?

I can’t imagine that I will not be able to continue working in the UK. I have never felt different from my UK or other EU or non-EU colleagues and I’m confident that will continue to be the case within the School. For now I am working as if nothing will change.

Of course there is a lot of uncertainty at the moment, around who can stay, access to funding, structure of future collaborations. But I know there is a lot of interest in this work and appetite to fund it. I am distraught by Brexit, but I have faith in humankind that a solution will be reached which ensures that valuable research that benefits the UK, Europe and the world will be able to continue in much the same way it does now.

Do you think other healthcare economists will follow in your footsteps?

Well there are not many of us and there is a lot of competition from a handful of leading universities in this field, such as Johns Hopkins and Harvard.

London, and LSHTM, will always have great prestige, but whether the best researchers continue to be drawn here will ultimately depend on whether funding is available to them. If some EU funding is withdrawn that will undoubtedly have an impact somewhere, and UK bodies may decide to make up the shortfall. The MRC, where I got my funding, was not obliged by the EU to fund non-UK students but it decided to do so in some cases anyway. For the sake of future UK research, I hope funding decisions continue to be taken to ensure the UK attracts the best and brightest and can continue to share its health expertise with Europe and the world.

Moving to London to study

Dr Diogo Martins, 27, from Porto, Portugal, moved to London in 2016 to take up an MSc in Public Health at the School. He has just completed an internship at the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva and is now returning to the School for his DrPH. He discusses the process, why he wanted to study in the UK, and his hopes for the future.

How did you end up here?

I qualified in medicine in Portugal and became very interested in public health. I was doing my public health medical residency which meant I had to do a Masters in Public Health.

I was keen to go abroad - I've worked at a number of different global health organisations over the last seven years - and I knew my best options were the US or UK and, for the UK, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine specifically.

The School had a very broad offering - even broader than the top schools in the US – so was my top choice. I applied, got accepted and I never looked back.

Why were you keen on LSHTM in particular?

The School has everything from hard lab science to health policy, it covers the global north and south, teaching, research, everything. It was so important to know that I would have seminars and lectures with people who had different perspectives.

I knew there was a broad representation of countries at the School. The fact people came from so many different countries was one of the reasons I wanted to come here.

What are the benefits of that diversity?

Much more than just accepting students from other countries, it's about how it is actively celebrated. They really want everybody to get a different perspective of the same topic. The studies and research we are told to read is all about getting different perspectives.

For example, in maternal health everyone was encouraged to talk about their own experiences - it was seen as important whatever country you were from as it provided different viewpoints. It's a really good way to empower and encourage diversity.

It also makes you feel welcome. My fellow students and I came from all over the world, but it still felt like we were a family - there was something connecting us. I've studied and worked in various places but this School got very close to my heart very quickly.

Are you worried about Brexit?

Brexit affected me practically because it happened when I was waiting for my offer. I was worried it would have immediate effects. But I received a letter from the School saying it would not have immediate consequences, which I appreciated – that allayed a lot of worry. I applied the next year for the doctoral programme to take advantage before the effect takes hold.

The topic comes up in classes and as a student ambassador I receive lots of questions and emails asking about it. For people I have spoken to, there are financial concerns and big question marks over career options if they want to stay on after their studies.

But I think the School is the place to be from a research perspective. Brexit is a brilliant case study of how national policy can really affect our health systems. People wouldn't see the School as part of that decision, but at the epicentre of where it's going to be discussed and analysed in a pragmatic, scientific way.

So you’re keen to stay?

Absolutely. I'm very excited to be coming back here for the DrPH - I'm moving to London and anything I do work-wise will be here. There are so many exciting organisations to work with in London.

London is expensive but it’s fun - there is too much on offer to sit at home!

To find out more about studying at the School, see our courses.

Brexit - information for students and applicants.

For staff and students, see the Brexit Hub for info.