A researcher uses a microscope at the MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM lab in Fajara. Credit: MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM

In March 2017, molecular biologist Martin Antonio was sitting at his desk in Fajara on The Gambian coast when he got an urgent call from the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Africa headquarters.

A deadly outbreak of meningitis had started 2,000 miles away in Zamfara State, Nigeria, and it was spreading rapidly. Scientists in the affected region had been unable to identify the pathogen involved and they needed help.

Doctors were able to treat patients, but without knowing which strain they were dealing with, the team couldn’t vaccinate healthy people - who were being struck down in the thousands.

Since December, scientists had been trying to work out the conundrum and finally called the WHO for help – who in turn contacted Prof Antonio, Principal Investigator and Unit Molecular Biologist at the MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM, their go-to expert on vaccine surveillance. “The size of the problem was staggering,” he remembers.

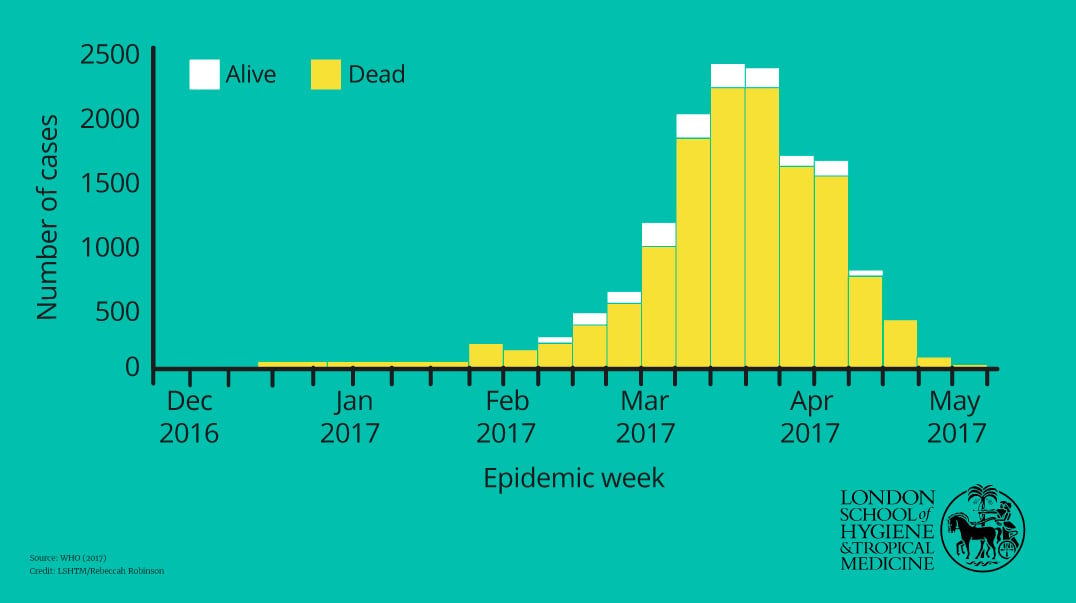

In Zamfara state alone, in a month there were more than 1,200 suspected meningitis cases, with 162 related deaths. By May 2017, there were 7,140 suspected meningitis cases and 553 deaths, making it an epidemic, as declared by the Nigerian Center for Disease Control.

Prof Antonio mobilised a rapid response team of six scientists and doctors who arrived five days later and identified the bacteria behind the outbreak - Neisseria meningitidis serogroup C - in just three days.

“When we found the pathogen, we had a Eureka moment! It was very satisfying.” - Prof Martin Antonio

With the help of the UK government, which donated 820,000 doses of the meningitis C conjugate vaccine, and GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, which funded a further 500,000, more than 1.3 million people in the two worst affected states of Zamfara and Katsina – or around 15% of the population – were protected.

Prof Antonio, who is the Director of the WHO collaborating Centre for New Vaccines Surveillance, based at the Medical Research Unit The Gambia at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM), said, “Nigeria had tried very hard, but they did not have the human resources or the laboratories. When we found the pathogen, we had a Eureka moment! It was very satisfying.”

Nigeria 2017 meningitis outbreak epidemic curve

The team had set up a mobile field lab in the back of a specially converted Land Rover to test samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from suspected patients, which gives a definitive diagnosis of meningitis. This complemented another lab they set up at the Ahmad Sani Yariman Bakura Specialist Hospital in the state capital Gusau, 120 km (75 miles) away. They worked closely with the Nigerian Centre for Disease Control and the Ministry of Health.

To diagnose and treat patients, MRC Unit paediatrician Dr Bernard Ebuke also trained more than 100 local healthcare professionals to perform lumbar punctures to get the CSF and set up a makeshift outdoor hospital.

“We had brought cutting edge science to the bush,” he said. “The Nigerians were very appreciative of our support. It was crucial.”

The team was known across West Africa for its expertise, having been called upon to conduct a similar exercise in Ghana the previous year, when a different strain of pneumococcal meningitis hit the country.

“We have an excellent technical platform, so we can do analysis very quickly and of high quality,” says Prof Umberto D’Alessandro, Director of the MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM. “I’m extremely pleased we were able to help.”

Saving lives with research

The expedition to Nigeria is a good example of what the MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM, in West Africa, and the Medical Research Council / Uganda Virus Research Institute and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Uganda Research Unit (MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit) in East Africa, aim to do – to improve people’s health and save lives through research. In addition, the Units train local people and build capacity.

Both units have been at the forefront of scientific and medical advances in Africa – in Gambia’s case for 70 years; in Uganda 29 years.

Their core income comes from the Medical Research Council United Kingdom, but such is their expertise and reputation that they win international grants and funds for many projects.

This year the MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM has a total budget of >£20 million, and employs 1,200 staff. Uganda has a £9 million budget and 400 staff. Funders include the Wellcome Trust, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) and international governments among others.

Both Units have internationally-accredited laboratories, with The Gambia’s Himsworth Laboratory being home of the World Health Organization Regional Reference Laboratory (WHO RRL), providing diagnostic services to the entire WHO African Region. Activities span from basic research in immunology, microbiology, virology and molecular biology to large epidemiological studies, intervention trials and routine clinical diagnosis.

Take a 360 look outside The Gambia research site

A 360 look inside a laboratory at MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM

The MRC Unit The Gambia at LSHTM also houses a biobank, with one million DNA samples, while the Unit in Uganda hosts the national and regional reference laboratory for HIV drug resistance.

And crucially, both Units offer clinical care to local people based around their headquarters and field stations – often in areas with very few health facilities.

A famous malaria experiment

In The Gambia, work began soon after the end of the Second World War, when the country was still a British colony. Food was in short supply and the nutrition needs of its people were paramount. The Unit was based in Fajara in a former military hospital on the coast, located on Atlantic Boulevard.

In 1949 Dr Ian McGregor, later considered by some to be the most eminent malaria expert in the world, joined the Unit to study the relationship between parasitism and nutrition and became its director five years later.

McGregor established a rural field station in Keneba, several hours’ drive eastward from Fajara, including a ferry crossing, which initially focussed on nutrition science. But within a few years, the focus turned to malaria in the country where the Anopheles gambiae mosquito, responsible for more malaria deaths that any other mosquito, was first described.

Dr McGregor, a parasitologist by background, conducted what is seen by many to be the most famous experiment in malaria control.

At the time, it was not known whether humans could develop immunity against malaria, like other infectious diseases such as measles, known as acquired immunity. He took blood from adults who had previously suffered from malaria and gave it to infected children and showed that this cleared the parasite, proving that antibodies could protect from malaria.

His findings were published in 1964 and were the first real proof that humans can build up an immune-response to the disease -- vital for encouraging vaccine development.

Dr McGregor’s work was taken further by his successor Dr, now Prof Sir, Brian Greenwood, appointed as Director of the MRCG from 1980-1995.

While Dr McGregor was more lab-based, Dr Greenwood was more focused on clinical research, in particular on the prevention and treatment of malaria.

Shortly before his arrival, the MRC Dunn Nutrition Unit based in Uganda was relocated to Keneba and came under the scientific direction of the Dunn Unit in Cambridge. In response, the MRC supported the establishment of two new field stations, one at Basse, at the far end of the country, and the other in Farafenni on the north bank of The Gambia river close to the northern Senegal border, chosen because there were very poor roads and no health services.

Investigating childhood killers

At the new Farafenni research centre established in 1983, Dr Greenwood went on to research causes of death in children in typical rural villages in The Gambia by carrying out post-mortem questionnaires asking parents and other family members about the circumstances of the death of their child. Malaria was the most important cause, but to his surprise the next was pneumonia – not considered a disease of the tropics at that time.

This revelation led to further research over many years with the Unit soon becoming instrumental in developing and studying the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), which prevents the childhood killers pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis. When the Unit’s research was published in The Lancet in 2005, pneumonia killed two million children a year worldwide. The paper recommended that all African children should be given the vaccine.

In 2009, the 7-valent vaccine (PCV7) was introduced under The Gambia’s national PCV programme, followed by the 13-valent vaccine (PCV13) in 2011. By 2015, the global pneumonia death toll was down to 920,000. Research by the Unit’s Grant Mackenzie, published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2016, showed that the vaccine has decreased the incidence of invasive bacterial diseases in Gambian children by 55% between 2008 and 2014.

Current Director Prof Umberto D’Alessandro considers this one of the Unit’s most impressive achievements, along with its research in shaping the country’s vaccination schedule. The other is their work toward decreasing another childhood killer – malaria.

Back in the early 1980s, Dr Greenwood continued his work studying Gambian villages and observed that many families in rural parts of the country used bed nets. The cloth used to make the nets came via boats from Liverpool; once made they were sold by local boys on bicycles going door to door. They were commonly given as part of a woman’s wedding dowry.

People used them for different reasons: the sometimes fairly thick material provided privacy at night for people who shared rooms with a number of people, according to Dr Greenwood, and protected users against falling roof debris.

But nets also guarded against the nuisance of being bitten in a country where at the height of the malaria season there might be over 100 mosquitoes entering a bedroom.

At the time, it wasn’t widely known that mosquitoes caused malaria and there was little evidence that nets were efficacious in preventing malaria.

So, Prof Greenwood did a formal trial which showed just that.

In 1985, he looked at the use of insecticide treated nets, which were just becoming available, versus non-treated nets. The idea of using chemicals to combat biting insects went back to WW2 when studies in Florida by the US Department of Agriculture found that Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was an effective vector control, and as a result it was used mainly as an indoor spray.

While there was some success with DDT, the pyrethroid group of insecticides were much safer and were used first to impregnate clothing to protect people, particularly the military, against bites by mosquitoes and other insects.

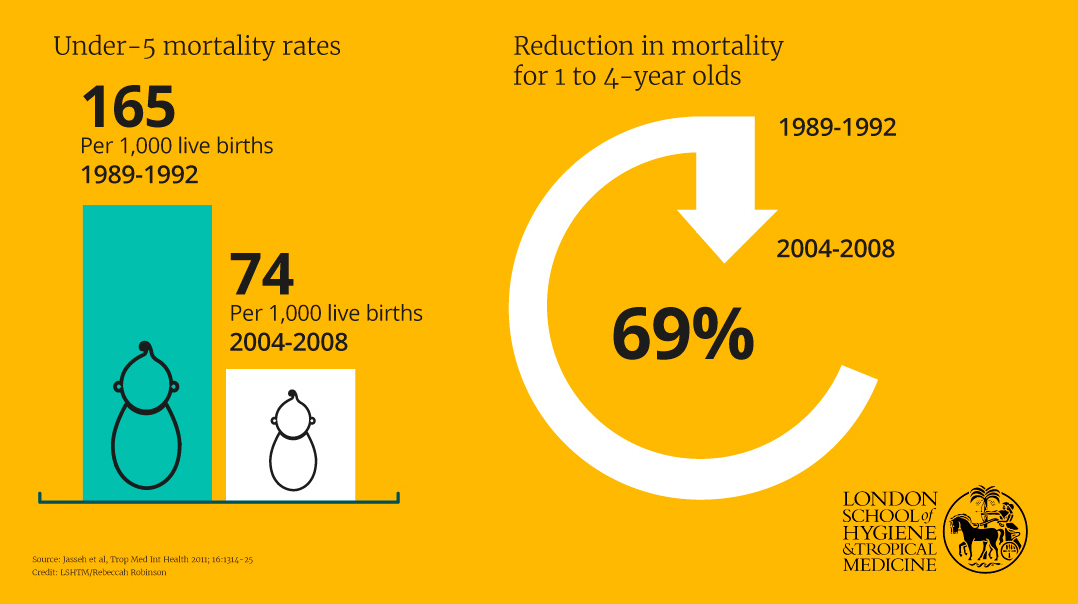

Decrease in childhood mortality in Farafenni, The Gambia

A small initial trial, followed by a larger one, proved that the treated bed nets were stopping more children dying from malaria. The larger study, led by Dr Pedro Alonso, now Director of WHO’s Global Malaria Programme, was published in The Lancet in 1991 and showed that sleeping under impregnated nets was associated with an overall reduction in mortality of about 60% in children aged 1-4 years.

WHO then provided funds for similar studies in Ghana, Kenya, Burkina Faso, while in 1992 a National Bednet Programme began in The Gambia, evaluated by Prof D’Alessandro.

This showed that insecticide-treated bed nets in The Gambia reduced overall child mortality (not just from malaria) by about 25% in the under-10s. These results were published in The Lancet in 1995. Bringing the results of these trials together WHO was confident to recommend the use of insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs) in all areas where malaria is a problem.

Prof Greenwood, Manson Professor of Clinical Tropical Medicine at LSHTM, remembers: “Research in The Gambia was very important in persuading the WHO to recommend the use of ITNs in all malaria endemic areas.

“It’s been shown since that malaria deaths have gone down globally from about a million a year in 1950 to just under half a million in 2017 and it’s reckoned that about 70% of that is due to use of insecticide in nets. It’s saved millions of children’s lives. This was pretty important research.”

Uganda’s MRC Unit would soon do similar for the control of another infection – HIV.

Proving what works

When the HIV epidemic first unfolded, there was much work and research being done on the virus in the US and the West as a whole, but there was little information about its spread in rural Africa. Work done in Uganda plugged these knowledge gaps and informed policies on prevention which had a huge impact on the later decline in prevalence of the disease.

Prof Pontiano Kaleebu, from Kawanda, north of the capital Kampala, was a young doctor in the mid-1980s seeing family members and friends die from a new disease called AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome).

First observed in the US in 1981 and first called AIDS the following year, by 1983 there were 16,500 AIDS deaths globally and 404,000 new infections.

Around this time (1982), doctors in rural Uganda had reported a wasting disease they called ‘Slim’ in a Lancet report but they could not see a link with the cases of gay men dying in North America reported across several cities.

At the start of the epidemic in Uganda, people did not know exactly how the virus was being transmitted, nor whether it was transmitted by insects or injections.

But by 1983, the first AIDS cases were recognised in Uganda by doctors who now saw the link, with 900 cases reported by 1986 and 6,000 by 1988.

By 1986–1987, 86% of sex workers and 33% of lorry drivers studied were HIV positive and 14% of blood donors and 15% of antenatal clinic attendees in major urban centres were also HIV positive. In response, the new President of Uganda Yoweri Museveni started an educational campaign around ABC - Abstain, Be Faithful or use Condoms. He called for ‘zero grazing,’ telling people to love carefully.’

Though it was then known that HIV was heterosexually transmitted, there were no available data on risk factors for transmission or of rates of disease progression in rural African settings. Scientific information on this new disease was mainly emanating from urban centres, cities like Kinshasa in neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo.

The Unit, formerly known at the MRC/UVRI Uganda Research Unit on AIDS, was established in 1989 to fill those gaps about rural transmission.

“We had a new disease, we didn’t know much about it, there was no treatment, there was no vaccine, and it was killing our own classmates, our relatives.” - Prof Pontiano Kaleebu

The UVRI in Entebbe had a long history going back to 1936, when it had been set up as the Yellow Fever Research Institute by the Rockefeller Institution, and had since expanded its remit. When Uganda appealed to the British government to help advance scientific knowledge to combat AIDS, it was the obvious choice for a collaboration with the MRC.

Prof Kaleebu, now the Unit Director, told us: “I saw my first case of AIDS in my final year as a medical student in 1985. There were lots of unknowns.

“That was one of the reasons I said I wanted to join the Uganda Virus Research Institute Unit, which I knew had started doing AIDS research. We had a new disease, we didn’t know much about it, there was no treatment, there was no vaccine, and it was killing our own classmates, our relatives.”

The Unit began studies into prevalence and incidence of the disease and the likely transmission of the virus, led by its first Director, Dr Daan Mulder from the Netherlands, working with Ugandan epidemiologist Dr Jane Kengeya-Kayondo and other colleagues in Uganda and at LSHTM.

They set up a large population-based study of the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in Kyamulibwa, Masaka District in rural south-west Uganda. Their early work confirmed that people were at higher risk if they had multiple sexual partners and that young women had a higher risk of infection than men.

One of the most important initial findings to emerge from the research programme was the first demonstration in a population-based study in Africa of the enormously increased mortality rates among those who were HIV-infected compared with uninfected people.

Dr Mulder’s 1994 study showed that the proportions of deaths that would have been avoided in the absence of HIV were 44% for adult men, 50% for adult women and 89% for all adults aged 25–34 years.

The results did much to destroy the credibility of the views of a vociferous few, who believed that the size of the AIDS epidemic was being greatly exaggerated and that HIV was not the cause of AIDS.

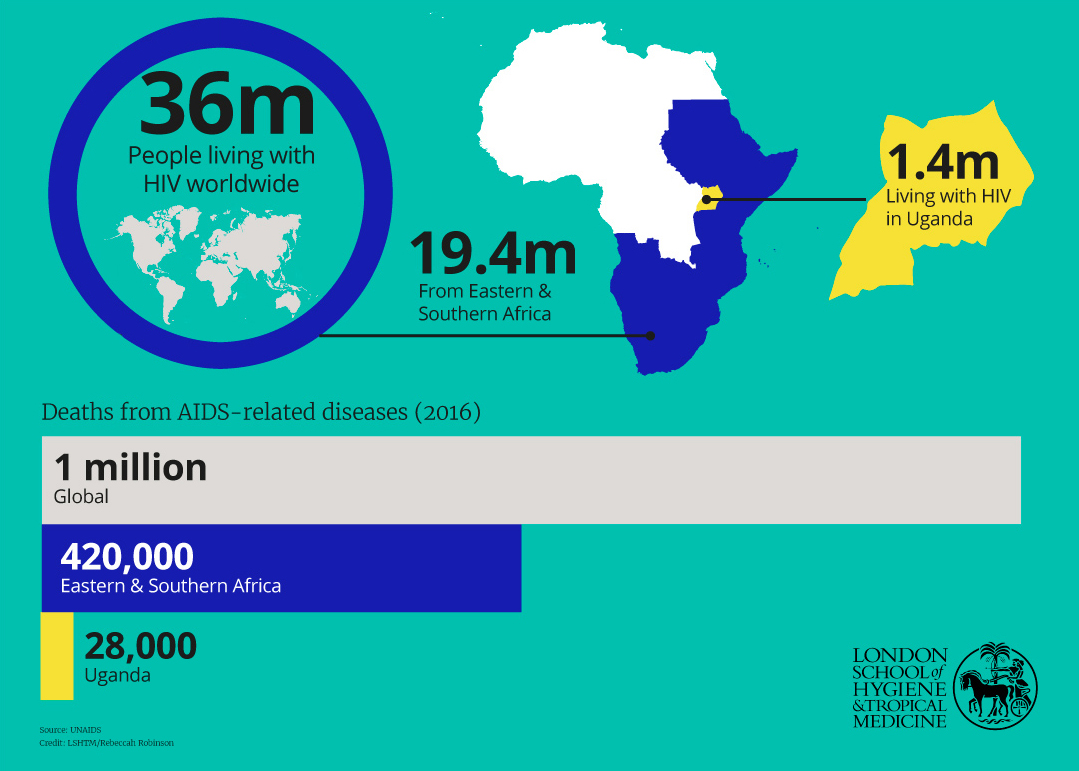

HIV/AIDS prevalence worldwide (2016)

Other studies in the mid-90s and early 2000s showed a decline in HIV prevalence in certain age groups, especially among young adults, indicating that there were ways of controlling the epidemic.

Next, the Uganda Unit followed individuals in a five year ‘natural history cohort study,’ from seroconversion – the period of time during which HIV antibodies develop and become detectable. This meant researchers could study people in rural Uganda from the time they were infected, to the time they developed symptoms, developed AIDS and died.

Prof Kaleebu said it was challenging as some participants did not want to know their HIV status, so the team enrolled people who were HIV negative as controls to follow, so they and the local community would not know who was positive when coming to the clinic. Only when the person developed symptoms did the participant realise that they had HIV.

The researchers found, unexpectedly, that survival times were not dissimilar to those described in high-income countries before the use of antiretroviral therapy (introduced in Uganda in 2004.) They also established for the first time that the time from infection to the development of AIDS took about 10 years, like patients in North America and Europe.

But once they developed AIDS, the time to death in Uganda was very short, under a year, less than half of those in the northern hemisphere.

In Prof Kaleebu’s own work, he identified different strains of HIV virus, establishing that subtype A and D were most common in the rural south Uganda, and that disease progression differed between them.

Other research done by Dr Rosalind Parkes-Ratanshi and others at the Unit, discovered the importance of the anti-meningitis drug Fluconazole used prophylactically with HIV patients.

The dramatic decline in HIV prevalence in Uganda has been hailed as ‘one of the world's earliest and most compelling AIDS prevention successes,’ attributed to successful behaviour change campaigns, led by national Government and NGOs, persuading people to reduce the number of sexual partners and encouraging fidelity.

Although it has been reported in 2004 that cases peaked at around 15% in the early 1990s and falling to about 4% by 2003, Prof Kaleebu believes now that more conservative figures are accurate – perhaps 10% at its height, reducing to 6.3%.

But rates of the infection are now appearing to rise, meaning the country, and region, still face a huge challenge ahead.

Of the 36 million people living with HIV in 2016 worldwide, more than half (19.4 million) were from eastern and southern Africa, where 420,000 died in the same year. This compares with 18,000 in western and central Europe and North America.

In Uganda alone, 28,000 people died of AIDS related diseases in 2016, and 1.4 million were living with the disease. Annual new infections are projected to grow rapidly to around 340,500 in 2025 – up from 52,000 in 2016.

By the early 2000s, phase lll HIV-1 vaccine trials were being carried out in North America and Thailand and many commentators predicted that it would be difficult to conduct trials of HIV vaccines in Africa – which were later borne out, with potential participants fearing becoming infected and believing they were being experimented on, according to the Unit’s researchers.

By 2002, the Unit had taken part in the first trial of an HIV-1 vaccine in Africa – a randomised, placebo-controlled study in healthy volunteers at low risk of HIV infection. 45% of the active participants experienced a vaccine-specific response, compared with 5% of the control, and demonstrated some evidence of an immune response against subtype A.

This is significant because other HIV vaccine candidates, while shown to be safe, have not induced good enough immune responses, apart from the Thailand trial, RV144, where modest efficacy was reported.

More recently in 2011, the Unit was involved in the Strategic Timing of Antiretroviral Therapy (START) study in collaboration with the University of Minnesota, University of Copenhagen and many others, which built upon larger studies such as the SMART study of 2008 on when ART should be initiated.

The START study, of more than 4,600 HIV patients in 35 countries, published in 2015, proved that as soon as somebody is diagnosed as HIV positive, the earlier they start treatment, the better their outcome. The results have contributed to the adoption of the Test and Treat policy, in line with WHO guidelines, by the Ugandan Government.

“It is very satisfying to see these reductions of new infections and AIDS related deaths. At the peak of the epidemic, we saw many people dying in our workplaces and in our families, but this has reduced,” says Prof Kaleebu.

Providing healthcare – and skills

Central to the success of both Units in The Gambia and Uganda is the understanding that the local residents who enable research should be clinically supported as patients.

In Uganda, the Entebbe field station is integrated into the premises of the district hospital. The study clinic there offers HIV and general healthcare for about 4,000 study participants. They also provide HIV voluntary counselling and testing (VCT) services for the public.

All field stations in Uganda have health clinics attached and strong relationships with local hospitals for referral. For example, at the Kyamulibwa field station, they see 70 patients a day, with specially designated days for patients with hypertension.

“The MRC always accepted that it couldn’t do research in a community with limited access to health services without offering care,” he says. “The way in which this was provided varied from time to time and place to place but the principle was always respected.”

Even Prof Greenwood rolled up his sleeves and took part. “I insisted that anybody who was medically qualified spent some time doing clinical care. I used to do my outpatients once a week as

Director, just to show that if you’re doing research, you have to give something back, and that it is important to keep in contact with the groups that you are trying to help.”

Now at the main site in Fajara the Gate Clinic remains the outpatients’ department and there is a 42-bed hospital, seeing a total of 50,000 patients a year. “It’s the public face of the Unit,” says Prof D’Alessandro.

Another shared passion of the Units is training local staff. In The Gambia, this took off under Prof Greenwood who immediately started training the most junior staff and field workers who would go out with questionnaires. Little training of local staff had been done previously.

Junior staff had the opportunity to travel to the UK to gain BTEC qualifications as technicians. Others were able to study for Master’s degrees and PhDs through the Open University, and later BScs with the University of Westminster.

“As we move forward we hope to see the next generation of brilliant African scientists capable to define their own research agenda in their various countries, working in genuine partnership with scientists from the North and hopefully improving global health.” - Prof Tumani Corrah

Another former MRCG Director, and LSHTM Honorary Fellow, Professor Tumani Corrah, echoed the important contributions to training and development, as well as impactful research. Prof Corrah, who spent 35 years at the Unit, including 12 as Director, joined many leading global health experts at the 70th anniversary celebrations in The Gambia last November. The event highlighted the huge reach and influence made by Prof Corrah, along with directors, staff and collaborators past and present.

Prof Corrah said: “As we move forward we hope to see the next generation of brilliant African scientists capable to define their own research agenda in their various countries, working in genuine partnership with scientists from the North and hopefully improving global health.”

There has long been collaboration and partnership between the two MRC Units and LSHTM, on an informal and formal basis.

A global partnership to tackle disease

On 1 February 2018, the MRC Unit The Gambia and the MRC/UVRI Uganda Research Unit formally joined LSHTM. The transfers build on the existing strong relationships between LSHTM and both Units, ensuring even stronger scientific collaboration as well as new career opportunities for researchers. The hope is to boost research capacity into current and emerging health issues in Africa - and throughout the world.

The formal partnerships are part of the MRC’s long-term programme of transferring Units into a host University to bring strategic benefits to both parties. The 16 MRC Units in the UK have already been transferred, for example the MRC Institute of Hearing Research to the University of Nottingham and the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit to the University of Cambridge.

While LSHTM has enabled thousands of its students to study abroad on research projects conducted with its scientists, this will be the first time it has had permanent bases abroad.

The three bodies are ‘excited and optimistic’ about the new opportunities, according to Profs Kaleebu and D’Alessandro. Professor Peter Piot, Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, believes the new partnerships present major opportunities for all three institutions’ staff and research output.

“Our School becomes more global than ever and increases its access to research facilities and skilled researchers based ‘on-the-ground’, while the Units will reap the benefit of LSHTM’s global reputation and wide-ranging expertise,” he said.

“By working even more closely together, innovative and collaborative research projects can be developed which are needed to tackle major global health issues.”

Professor Sir John Savill, Chief Executive Officer of the Medical Research Council, said he was excited by the Units in Uganda and The Gambia becoming part of a new ‘family’, especially one that is world renowned for its work in global health.

“We know from experience that transfers like these are uniformly positive; transferred units are more successful in winning additional funding and their collaborations with partners increase. MRC researchers benefit from having the university working to nurture the research leaders of the future.”

The Unit Directors believe this unification will lead to better opportunities for training, such as Master’s courses, short courses and PhD fellowships, as well as access to greater expertise in non-communicable diseases such as cancer, diabetes and heart disease that are also rising in prevalence across the continent.

Prof Kaleebu adds that it will help with recruitment, as very senior and experienced scientists have been difficult to attract in the past because of the rural locations. Prof D’Alessandro says: “We already have a very strong relationship with the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. I think the partnership will create more opportunities and increase our capacity to do research in several new areas.”

Prof Antonio is hopeful about the future.

He believes the transfer offers a unique and rare opportunity to work together, and an extension of the Unit’s mission. “Both will contribute to, and benefit from, each other’s exceptional strengths in global health emergencies, as well as translating our world-class basic research into saving lives and improving health across the world in the many infectious diseases that we study.”