Cancer and big data (iStock/Elenabs)

This feature is available for republication under a Creative Commons licence.

"You have cancer.”

Every year, 17 million people around the world hear these dreaded words. Moments with doctors that change their lives, and profoundly affect those close to them. Stories about people with cancer, alongside news highlighting research being conducted into the disease, are constantly being reported. Whether it’s exciting new drugs, pinpointed surgical techniques using robots or therapies using genetically modified cells, there is every reason for people affected by cancer to be hopeful for the future.

The chance of surviving most cancers is indeed steadily increasing globally, with some sobering exceptions such as pancreatic cancer where the chance of long-term survival remains dismal, no matter where you live. In the UK, fifty percent of people can now expect to survive ten years or more after a cancer diagnosis. However, for any cancer treatment to be successful, an individual has to interact with a complex web of health services and navigate hundreds of decisions with healthcare professionals leading to diagnosis, treatments, appointments and eventually, perhaps life after cancer. But how well these systems work for individuals is remarkably varied, not just throughout the world, but sometimes even between people living on the same street, who would expect to receive the same standard of care.

To uncover why these disparities exist and to investigate important questions around the lasting impact of cancer on those who survive it, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) has a diverse group of researchers working on cancer survival. They often work with huge data sets, from up to 37 million cancer patients worldwide, investigating everything from patterns in survival, the mental health impact of surviving cancer or the long-term physical effects of cancer drugs, and the likely course of cancer for individual patients.

“We aren’t the type of cancer research scientists people often have in mind. We don’t wear lab coats or look down microscopes. What we study is, once people have cancer, how long they survive. It can seem a bit remote to people living with the disease or who have survived their disease, but it is beneficial to society and has real-world implications,” said Camille Maringe, a research fellow and statistician in the Cancer Survival Group at LSHTM.

Understanding why these differences in cancer survival occur and coming up with strategies to tackle them is the key goal of the Cancer Survival Group. The international group has over thirty researchers and is the biggest of its kind globally. Professor Michel Coleman is its head and has been working in epidemiological cancer research for more than three decades.

“For each type of cancer, we look for patterns and inequalities in survival according to where you live, whether the area is wealthy or deprived, whether you are young or old, and in particular, survival deficits with other countries,” said Prof Coleman.

"We aren’t the type of cancer research scientists people often have in mind. We don’t wear lab coats or look down microscopes. What we study is, once people have cancer, how long they survive."

Camille Maringe, Research Fellow at LSHTM

For example, LSHTM researchers found that five-year survival from breast, colorectal and lung cancer is lower in the UK than countries with similar taxpayer-funded healthcare, such as the Nordic countries, Canada, and Australia. The difference was found to be partly due to later diagnosis, which is well-known to result in poorer outcomes. However, this did not account for all of the disparity in survival.

“We showed that patients tended to be diagnosed at a later stage in the UK, but that even at a particular stage of disease at diagnosis, survival also tended to be lower in this country than in comparable countries,” said Prof Coleman.

This was a particularly surprising finding, indicating that treatments for patients with even the same stage of disease were also worse in the UK than in Nordic countries. These insights eventually led to the development of the National Awareness and Early Diagnosis Initiative in 2008 (NAEDI), which sought to improve early diagnosis for cancer, highlighting the capacity of big data to make real changes in society if the information is harnessed usefully.

“The research that we’ve done on cancer survival has underpinned national strategies for cancer, which are explicitly aimed at improving survival on the basis of our results,” said Prof Coleman.

Although the group rarely gets information about which specific drugs are used, as this detail is not typically stored in cancer registries, they can sometimes also see the effects from new targeted cancer drugs when they are rolled out. The imprint of these drugs in the datasets reveal sharp peaks in survival for a few, specific types of cancer.

“When a treatment that is relatively simple, becomes available quickly and is dramatically more effective than what came before, you can see sudden jumps in survival in some countries, such as with chronic myeloid leukemia after the introduction of imatinib, “said Prof Coleman.

Imatinib was the first cancer drug developed to specifically target a protein present on myeloid leukaemia cells, but which was sparse or absent on other types of cells. Introduced in 2001, first in the U.S. and soon after worldwide, it dramatically increased the chance of long-term survival for chronic myeloid leukemia patients.

Cancer survival and inequalities worldwide

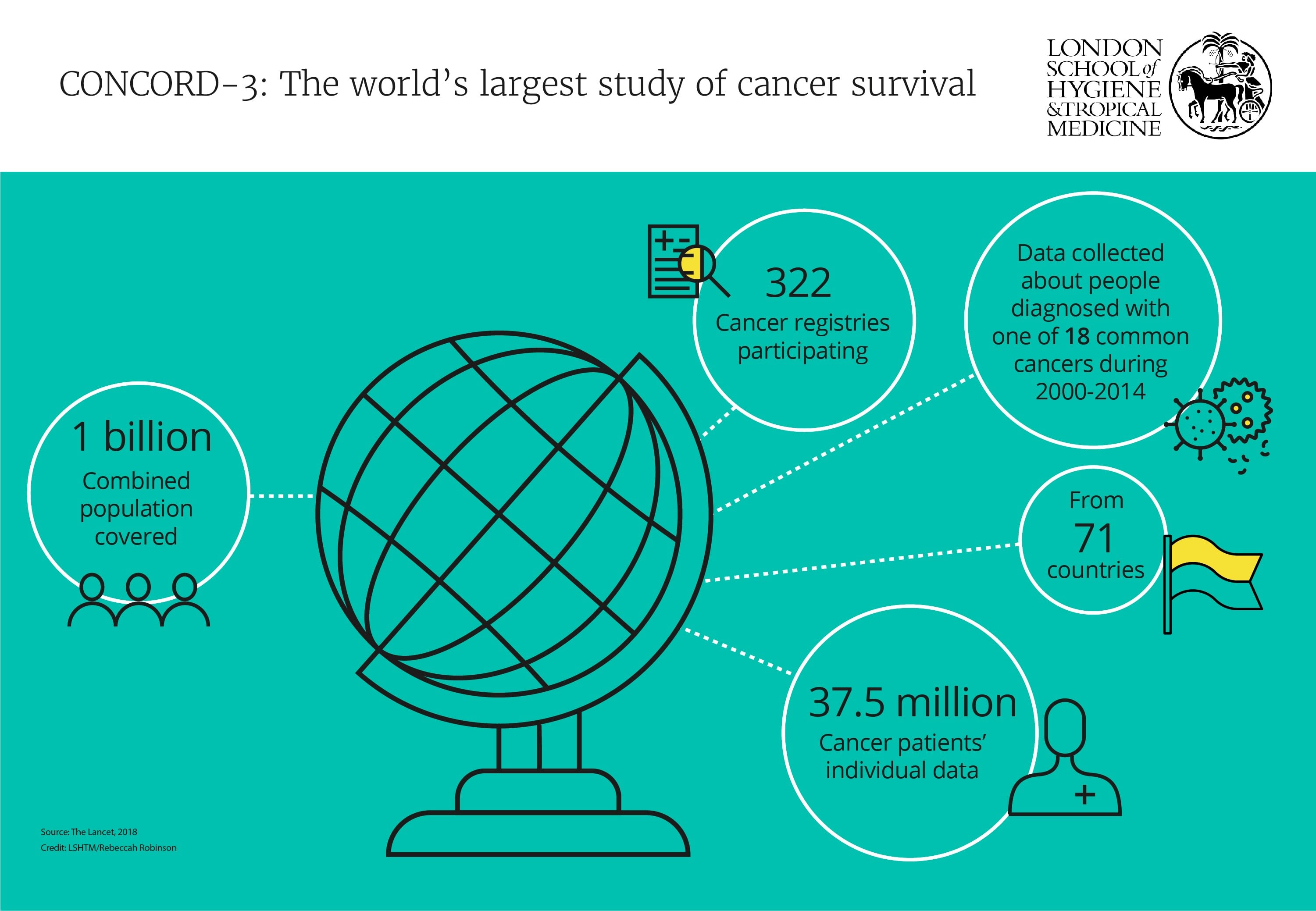

The scope and impact of the Cancer Survival Group’s research extends far beyond just a handful of countries, however. An ambitious research programme for global surveillance of population-based cancer survival trends, named CONCORD, collects and analyses cancer data from countries worldwide and identifies trends and disparities in survival.

The first CONCORD study, the biggest analysis of its kind to date, was published in The Lancet Oncology in 2008, involving data from 1.9million people with four different types of cancer in 31 countries. The most recent study, CONCORD-3, involves data from 37.5 million cancer patients diagnosed with one of 18 different types of cancer between 2000-2014, collectively representing three-quarters of all global cancer diagnoses annually and covering a population of one billion people living in 71 countries.

“We are dealing with the largest population-based database in the world of individual records from cancer patients,” said Dr Claudia Allemani who is co-leading the CONCORD programme with Prof Coleman. “We found a continuous increasing trend in survival for breast and colorectal cancers from 1995 to 2014. In general, survival is increasing worldwide for most cancer types, but there are some cancers such as lung, liver and pancreas where survival is not improving, which is bad news.”

In another instance, the huge database revealed that five-year survival was higher in South-East Asian countries than in other countries for gastrointestinal cancers, such as those of the stomach and oesophagus, but lower for melanoma of the skin and blood cancers. Higher gastrointestinal cancer survival may be linked to comprehensive screening and treatment programmes in the region, but the cause for low survival with melanoma and blood cancers is under investigation. Using differences like this to enable healthcare systems to learn from each other is a key aim of the researchers. To do this, healthcare systems and governments must have robust information on their performance in order to develop effective strategies and policies.

“Looking at a country where survival is high, you would go and check the health system, to see how it works and try to transfer what the system is doing well to another country,” said Dr Allemani.

One universal consideration in healthcare systems worldwide is how much money is spent. In terms of costs, research from LSHTM shows that available healthcare budgets are not directly proportional to cancer survival.

“Survival from cancer in Canada and the U.S. is roughly the same, even if expenditure in the U.S. is much higher than in Canada. If you compare Canada with Sweden, expenditure in Sweden is even lower, but survival is very similar. It is an important message - it is not only how much money is allocated to health, but how it is used,” said Dr Allemani.

The group also looks at differences in cancer survival between people within countries, based on factors such as ethnicity and socioeconomic information like wealth and education. What they have found is striking, even in some of the richest countries in the world.

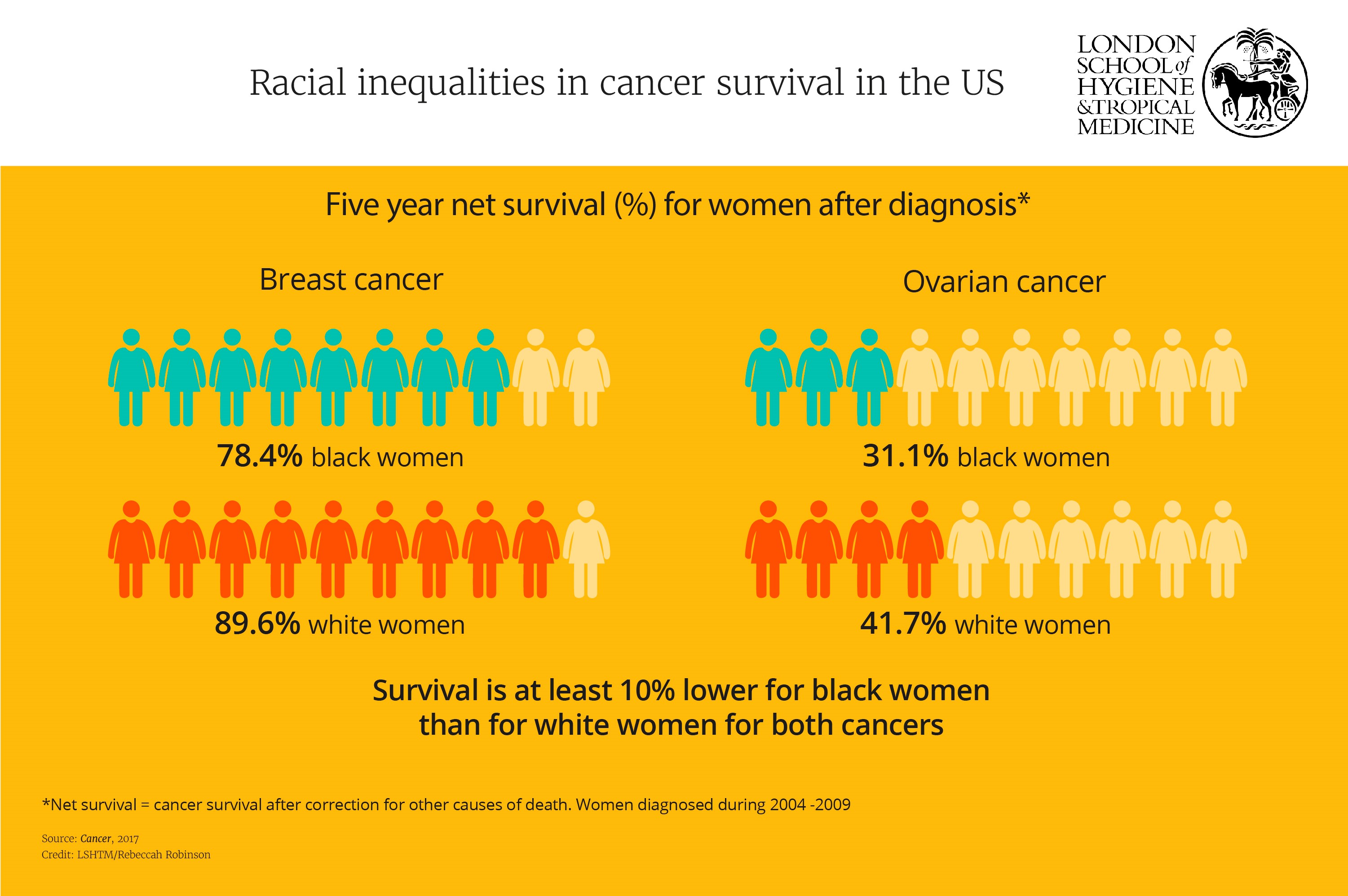

In 2017, Dr Allemani and her colleagues published a series of papers in the journal Cancer with colleagues at the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention, looking at racial disparities in survival between black and white people. Survival was persistently lower in black people than white people in the U.S. for almost every cancer. They note black people are often diagnosed at a later stage than white people, but that this alone is unlikely to account for the stark differences in survival.

“Even with breast cancer, which is considered to have a good prognosis, you will see a massive difference in survival between white women and black women. A high proportion of triple negative breast cancers, (an aggressive type typically diagnosed at a later stage), in black women cannot be the only explanation for the huge difference in survival. Especially because we see this difference for most cancers,” said Dr Allemani.

Dr Allemani has also found striking differences in survival for women’s cancers worldwide. This piqued her interest and she now leads a global project focused specifically on women’s cancers of the breast, cervix and ovaries. The CONCORD data will allow her to answer some, but not all, of her research questions. As a result, she was recently awarded a European Research Council grant to ask registries around the world to go back to medical records and collect new, more detailed information on stage, diagnostic procedures used to determine stage, treatment and molecular biomarkers. She will also collect information on socioeconomic and lifestyle factors, data which have never before been collected in such an ambitious, large-scale research project.

“First, we want to assess whether these cancers are the same biologically all around the world or if they are different between different populations, which could explain differences in survival. If the cancers are indeed biologically the same, then we will determine if differences in survival are due to variations in access to diagnosis and treatment or to other factors which prevent women from seeking treatment,” said Dr Allemani.

These other factors may involve societal considerations such as lack of awareness that prevent women from seeking advice from healthcare professionals on how to prevent cancer or gain access to early diagnosis. The data Dr Allemani will collect should help understand these drivers.

“The aim of all of these studies is to find actionable evidence for health policymakers to act on inequalities worldwide,” she said.

Why is UK cancer survival lower than in comparable countries?

LSHTM also has a great deal of research into UK-centred issues, starting with figuring out why the UK lags behind other comparable countries in cancer survival with a view to helping inform policymakers and healthcare providers as how best to tackle this.

“What happens in the management of the cancer patients here in the UK that leads to the deficit in survival? How can we make sure that everyone is receiving the care that they are entitled to?” said Camille Maringe, a statistician and research fellow.

In a 2019 study published in The Lancet Oncology, the researchers focused on colorectal cancer survival. They found that, as with many cancers, people diagnosed with colorectal cancer in England have a lower chance of survival -- in this case compared to Denmark, Norway and Sweden. One likely explanation is a reduced access to surgery for patients in England.

“What we found is that provision of surgery to remove the tumour in England wasn’t as good as in the Nordic countries for these patients at each stage of disease. We also saw that patients in England who were over 75 years of age had an even larger deficit in access to surgery than patients in other countries,” said Maringe. “This is not the only problem that can explain the deficits in survival, but it is an important factor.”

But what happens to this information and how does it contribute to improving the situation for people with cancer in the UK?

“The aim of all of these studies is to find actionable evidence for health policymakers to act on inequalities worldwide.”

Dr Claudia Allemani, Associate Professor at LSHTM

“Policymakers are aware that England is lagging behind in terms of cancer survival. Our studies get the attention of the right people and we’ve seen our work contributing to shaping policy and strategies to help tackle these differences in survival. Still, more needs to be done,” said Maringe.

“Population research has a fundamental role to play in our vision of 3 in 4 people surviving cancer by 2034, particularly in early diagnosis and prevention”, said Fiona Reddington, head of population research at Cancer Research UK, a leading cancer charity focusing on research and awareness. “Over many years we’ve funded some of the world’s best researchers in this field. Their work has led to the introduction of screening programmes and changes in prescribing regimens and clinical practice; now - with the revolution in big data collection and processing - such studies can be better integrated into discovery and clinical research, creating a two-way flow of information.”

Historically, awareness campaigns for improving cancer survival have been mainly focused on asking patients to do things differently. For example, to stop smoking, to exercise more, to check for lumps and to report any concerning health problems early to their doctors. These methods do of course have a role to play in increasing cancer survival, but researchers are asking whether there is more to be gained by questioning if there are discrepancies in healthcare systems affecting individual access to treatment.

Even within England and Wales, there appear to be big gaps in survival based on location, wealth and age at diagnosis, which cannot be explained by obvious factors such as other health issues.

Recent research led by Professor Bernard Rachet from the Cancer Survival Group, found that people from poorer backgrounds with the most common type of lung cancer were less likely to be offered potentially life-prolonging surgery than those from wealthier backgrounds. This was even after taking into consideration elements such as additional health problems which those from poorer backgrounds might be more likely to experience.

“Even when we adjust for all of these factors, patients from poorer backgrounds still tend to live shorter lives with cancer. We want to find out what is it that makes it more difficult for patients from less affluent backgrounds to benefit equally from healthcare services compared with patients from more affluent backgrounds,” says Maringe.

There was also evidence that older people would not be offered life-prolonging surgery even if they were in good health otherwise, for no other reason than their advanced age.

The team used a new statistical modelling technique to assess a group of patients over 70 who were not offered surgery, but could have been, based on their stage of disease and overall health. They predicted that these patients would have achieved a 10% increase in survival at one year if they had been given surgical treatments.“I think it’s important to use our data to generate further evidence so that treatment is offered to all patients who would benefit from it, regardless of their age,” said Maringe.

Navigating the healthcare system and optimising palliative care

Dr Tom Cowling is an assistant professor in clinical epidemiology at LSHTM, who was recently awarded a skills development fellowship from the Medical Research Council. One of Dr Cowling’s main projects involves collecting data from people diagnosed with colorectal cancer to develop a model to predict how each cancer patient will fare. The rationale for developing this model is to help hospitals and healthcare teams better prepare for the needs of each patient, as well as preparing the patients themselves, by removing some of the anxiety and uncertainty about their cancer prognosis.

“I’m trying to predict the likely course of cancer for each patient so doctors are better informed about likely outcomes for the person in front of them under different scenarios, so that they can make the best decisions for that patient,” he said.

Cowling and his team use records from about 40,000 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer each year in 156 hospitals and treatment centers in England and Wales. As well as diagnosis information, the database contains millions of pieces of separate information about everything from admissions to hospital, stage at diagnosis, chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatments and outpatient appointments.

There is substantial evidence suggesting that providing palliative care earlier in the disease course rather than in just the last few weeks or months of life, leads to a better quality of life and less aggressive treatment, such as stays in intensive care or receiving chemotherapy which is unlikely to substantially prolong life, but often comes with a host of unpleasant side-effects.

“A main use of this kind of model is that if you identify patients who have a particularly poor prognosis early on, you can put together a supportive care package to make the end of their life as good as it can be given the circumstances,” said Dr Cowling.

Cowling is looking at a range of statistical methods and techniques to form these models, including new, innovative approaches involving machine learning. The ultimate aim is to have a model that can progress with the additional information collected for each patient for each month then refresh its predictions, evolving over time with each patient’s cancer journey.

“I think doctors are always trying to forecast the future when making treatment decisions. That kind of mental forecasting they do, I’m trying to make that decision-making process a bit more systematic, by providing formal statistical models,” said Dr Cowling.

Surviving cancer, but at what cost?

More people are surviving cancer than ever before, but many treatments have toxic side effects which are acutely obvious to anyone with experience of or witnessing others with cancer – hair loss, pain, nausea, fatigue being the more commonly-reported symptoms. However, with growing numbers of cancer survivors, it is increasingly apparent they can experience long-term health effects as a direct result not of their original cancer, but of the treatments used to save their lives.

Professor Krishnan Bhaskaran, a Wellcome Trust/Royal Society Sir Henry Dale Fellow at LSHTM, has been using the medical records from 15 million people in the UK, which includes hundreds of thousands of cancer survivors, to see if he can identify the risk of cardiovascular side effects for specific groups of cancer survivors.

“We are keeping people alive longer but want to minimise long-term effects of their treatment. My work is looking at the long-term health of people who have survived,” said Prof Bhaskaran.

One particular class of chemotherapy agents; anthracyclines, are well-known to put patients at risk of cardiovascular side-effects, sometimes several years after the initial treatment. They are used in a few different types of cancer, notably blood cancers like leukaemias and lymphomas and breast cancer, the latter being one of Prof Bhaskaran’s particular current research interests.

“We are keeping people alive longer but want to minimise long-term effects of their treatment. My work is looking at the long-term health of people who have survived.”

Prof Krishnan Bhaskaran, LSHTM

“Our ultimate aim is to let cancer patients and health professionals know where the risks are. We want doctors to know whether they need to consider cancer history when looking at cardiovascular health. If there are increased risks of some cardiovascular outcomes for specific groups – the next step is predicting people’s individual risks so you can intervene and prevent.”

Women with breast cancer often receive radiotherapy treatment to the breast tissue. If the left breast is treated, this can cause cardiovascular problems when the heart and nearby arteries and veins may get an unwanted dose of radiotherapy.

“Radiotherapy and shielding techniques have greatly improved over recent years meaning that old data on cardiotoxic side-effects is not necessarily that relevant now. What we have is a moving target,” said Prof Bhaskaran.

This ‘moving target’ is not just the changing use of radiotherapy. Breast cancer survival in the UK has increased dramatically over recent decades from 53% of people surviving for at least 5 years after diagnosis in 1971 to 87% in 2011. This increase is partly due to changes in treatment, with recent decades seeing the development of several new drugs, including tamoxifen, herceptin and aromatase inhibitors. Although undoubtedly beneficial to patients’ survival chances, less is known about how these new treatments affect people long-term.

Cardiovascular complications are not the only side-effects that those who have had breast cancer experience. PhD student, Helena Carreira is looking at the mental health of breast cancer survivors.

Carreira was the lead author on an analysis of 60 previous research papers, finding that up to half of breast cancer survivors had anxiety, and up to 1 in 3 had depression. Subsequently, Carreira is doing her PhD project with Prof Bhaskaran on this topic, looking at an extensive collection of patient data records for incidences of diagnosed clinical depression, anxiety and suicide. A smaller cohort of patients as well as people of similar ages who have not had breast cancer will receive questionnaires to delve more deeply into their mental health, as well as any financial concerns and issues with sexual health.

“Although many people do survive cancer with few or no long-term problems, as survival rates improve, more people are likely to be living with the residual impact of having had cancer,” said Martin Ledwick, Cancer Research UK’s head information nurse. “So we need more research to properly understand the scale and variety of the problems cancer survivors will face, and to find out what interventions are likely to be most helpful. The more we understand about cancer survival, the better we will be able to recognise and treat these long-term side effects.”

Members of the National Cancer Institute Consumer Forum attend a meeting at LSHTM with members of the Cancer Survival Group. The forum includes patients, carers and others affected by cancer. © Simon Callaghan Photography

Working with cancer survivors

Working with survivors and family members of people who have lost their lives to cancer has always been part of LSHTM’s strategy. Researchers work closely with the National Cancer Research Institute (NCRI), a UK-wide partnership of cancer research funders. The NCRI Consumer Forum consists of cancer survivors, patients and family members who are instrumental in helping the NCRI make decisions on policy, strategy and campaigns, as well as being involved in individual research studies and projects.

Richard Stephens chaired the NCRI’s Consumer Forum from 2012 to 2019 and is a survivor of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Cancer Survival Group at LSHTM hosted a full day with NCRI consumer representatives in 2012 and again in 2017, with researchers presenting their work and facilitating a Q&A and workshop sessions to get patient input into their research.

“For many of us, in 2012 it was our first experience of epidemiology,” explains Stephens. “Most of us had experience in clinical trials, quality of life research or basic science. Learning about the work of the Cancer Survival Group at LSHTM made most of us converts to epidemiological studies from that moment onwards. In our meetings now, we quote data to each other left, right and centre!”

Data from cancer patients in England and Wales is automatically collected by cancer registries unless individuals opt out, but research has shown that patients and survivors overwhelmingly do want their data to be used and are increasingly interested in being involved in dictating what happens to their data.

“Researchers are using our data and if we want to be involved, we should be, it is our data. We know this data is valuable and we want to know what they do with it,” said Stephens.

“For me now in cancer research, one of the fundamental new areas of focus is about the people who survive. What secondary effects are these people dealing with? How many people who have had particular drugs to treat their cancer will then, like me, have health problems related to those drugs later on? To work all this out we need data about different groups and populations – we need as much data as we can get to help as many people as we can.”

Influencing policy to improve cancer survival

Research questions and policy changes are often driven by advocacy from patient and carer groups like this, backed up with robust data and conclusions from researchers such as those at LSHTM. It is, simply, a collaborative relationship where the impact of the work from both groups is enriched by working together.

“I’ve been doing this for twenty years and I can see things now – changes in eligibility ages for clinical trials, funding committees have patients on them – I can see things that we helped start off 15 years ago have now become run-of-the-mill,” said Stephens.

“I’m passionate about public health and cancer research. We try to ensure that government strategies on cancer control are best fitted to improve the lives and outcomes of cancer patients around the world.”

Prof Michel Coleman, LSHTM

New cancer treatments are being developed and approved at a faster rate than at any time in history and our health systems are constantly evolving. Using big data to examine cancer survival and trends across populations is crucial to identify successes and highlight blockages to make sure that effective treatments are reaching all the people who need them. This research also plays a vital role in helping recognise, understand and address the long-term effects of treatments that can affect the quality of life of the growing number of cancer survivors.

“What we do in our research is aimed at helping people,” said Prof Coleman. “I’m passionate about public health and cancer research. We try to ensure that government strategies on cancer control are best fitted to improve the lives and outcomes of cancer patients around the world.”

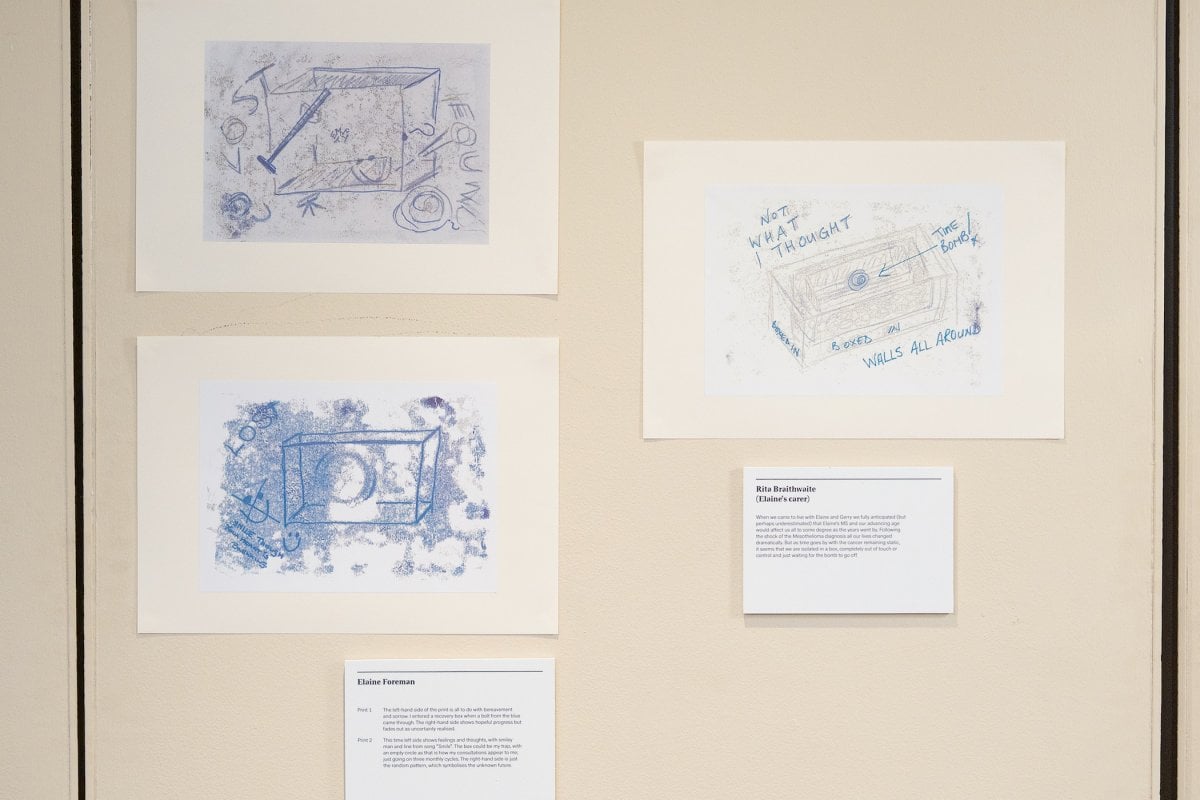

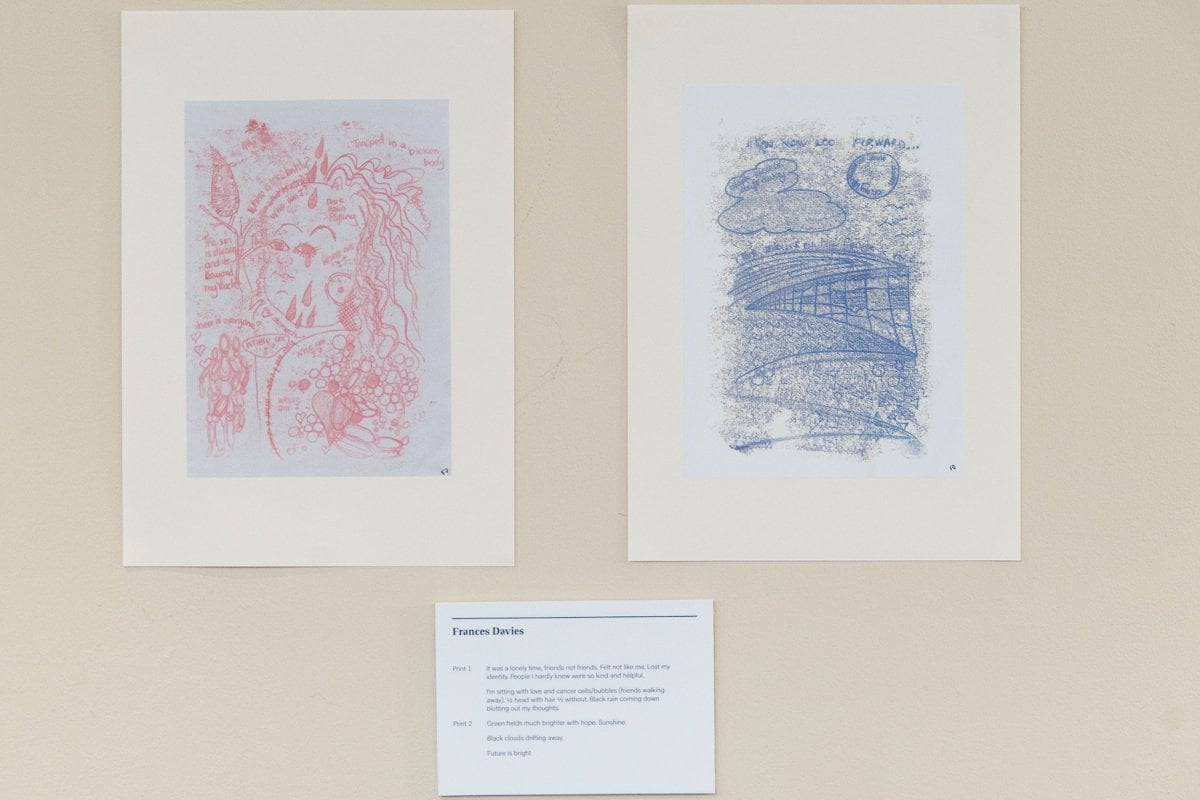

A cancer diagnosis is life changing. Changes to the body, emotions, and relationships with family and friends can feel inexpressible. Art can act as a form of release and is a way of bringing people together to share experiences through a creative process. Our Cancer Journey was a workshop initiated by LSHTM that brought together three researchers, two artists, one carer, and seven people living with cancer to share experiences of how cancer had affected their lives. The resulting exhibition contains two mono-prints for each participant, representing different stages of the cancer journeys of those living with the disease. The workshop took place in Newcastle in November 2018 and was funded by the LSHTM Public Engagement Small Grants Scheme.

We hope you enjoyed reading about our work in this feature. If you are interested in supporting projects like these and the many others we are leading to improve health worldwide, we would be delighted to hear from you. There are many ways you can make a gift to the School, from wherever you are in the world. Each and every gift we receive makes an impact, from funding scholarships, to updating our facilities or investing in new avenues of research. Whether it’s a gift of £5 or £500,000 your generosity will support our mission to improve health in the UK and around the world.