Dr Laura Cornelsen conducts research on food choices and sugar tax at LSHTM. Image credit: Christian Sinibaldi

Sandra Williams knows about the perils of sugar. In 1998, aged 24, she spent six months in hospital recovering from a terrible car crash, which caused a stroke. Once discharged, she had one leg in a caliper and was unable to use her right hand.

Bored and immobile, she began drinking huge amounts of fizzy drinks – and the weight soon piled on.

“I would drink three or four cans of Coke a day, plus Sprite and other fizzy drinks,” Williams explains. “On Thursdays and Fridays down the pub I would drink Red Bull. I was bored, bored, bored,” she says.

When her weight reached 19 stone Williams, who worked as a butcher in Bishopstoke in Hampshire, UK, before the crash, realised she needed to do something and joined Weight Watchers.

Now, aged 44 and several stone lighter, she’s ditched the high sugar varieties and limits herself to two cans of Diet Coke a day.

There’s a huge difference in sugar and calorie levels between regular and diet versions of soft drinks – for example a 330ml can of Diet Coke has no sugar and just 1 calorie, compared with 35g of sugar (7 teaspoons) and 139 calories in Coca Cola Classic, which works out at 10.6g per 100ml.

The UK sugar tax

But Williams appreciates that for others, weight loss alone may not be enough of an incentive to choose healthier options. Many just love the taste, others dislike the artificial sweetener, and some don’t like being told what to drink.

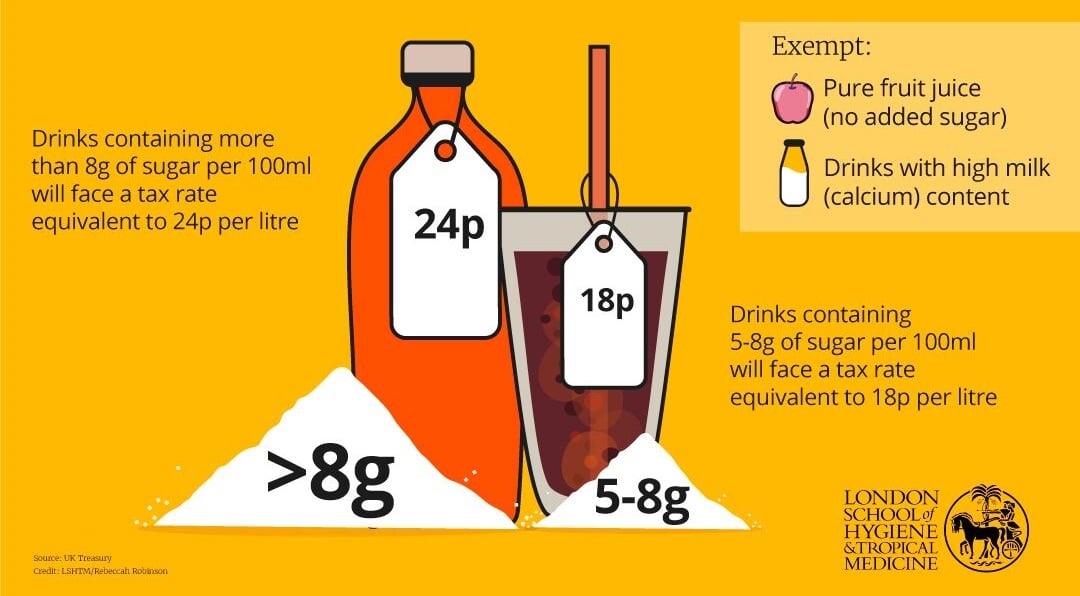

To make the choice easier – or harder depending on how you look at it - the UK recently launched a ‘sugar tax’ on sweetened drinks. Officially called the Soft Drinks Industry Levy (SDIL), the tax puts a charge of 24p on drinks containing 8g of sugar per 100ml and 18p a litre on those with 5-8g of sugar per 100ml, directly payable by manufacturers to HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC).

It was introduced in April 2018 as part of the Government’s childhood obesity strategy and it aims to reduce sugar consumption by persuading companies to reformulate their high sugar brands and avoid paying the levy.

If they don’t reformulate, it’s up to manufacturers to decide whether to pass the levy cost on to consumers.

It’s not the first effort to reduce sugar in the UK. Last year, Public Health England (PHE) called for a 20% cut in sugar content within food produce by 2020, with 5% being the target for the first year. However a new PHE report released in May found that food manufacturers and supermarkets have only managed to cut 2% of sugar content.

Meanwhile the obesity figures continue to rise relentlessly.

According to NHS Digital, more than a quarter of English adults are now obese – including 2% of men and 4% of women who are classed as ‘morbidly obese’ with a Body Mass Index of more than 40.

BMI is a widely-used measure of whether someone is over- or underweight, calculated by dividing their weight in kilograms by the square of their height in metres.

English hospital admissions directly attributable to obesity rose by 8% between 2015 and 2017 to 10,705. And there were 6,700 bariatric surgeries conducted in hospitals across England from 2016 to 2017 – 77% of them on women.

In the soft drinks aisle at her local Tesco supermarket in Winchester, Hampshire, Sandra says the sugar tax is a “really good idea”.

“I love it,” she says with enthusiasm. “Children need healthy diets and adults in the UK are increasingly morbidly obese. If anything, I don’t think it’s enough.”

She admits that an extra 24p wouldn’t have been enough to put her off during her younger years. “When I was drinking high-sugar drinks, I had the money and I would have bought it.”

But she also admits she does not want to be obese again.

Dr Laura Cornelsen, assistant professor in public health economics and MRC Career Development Fellow at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, says this highlights that changing behaviour is really difficult, particularly when people who have been used to the same product for years say they really like it.

“It’s very individual,” she comments. .“Changing behaviour is really difficult and strong preferences and habits mean the price responsiveness is likely to be lower.”

A growing global trend

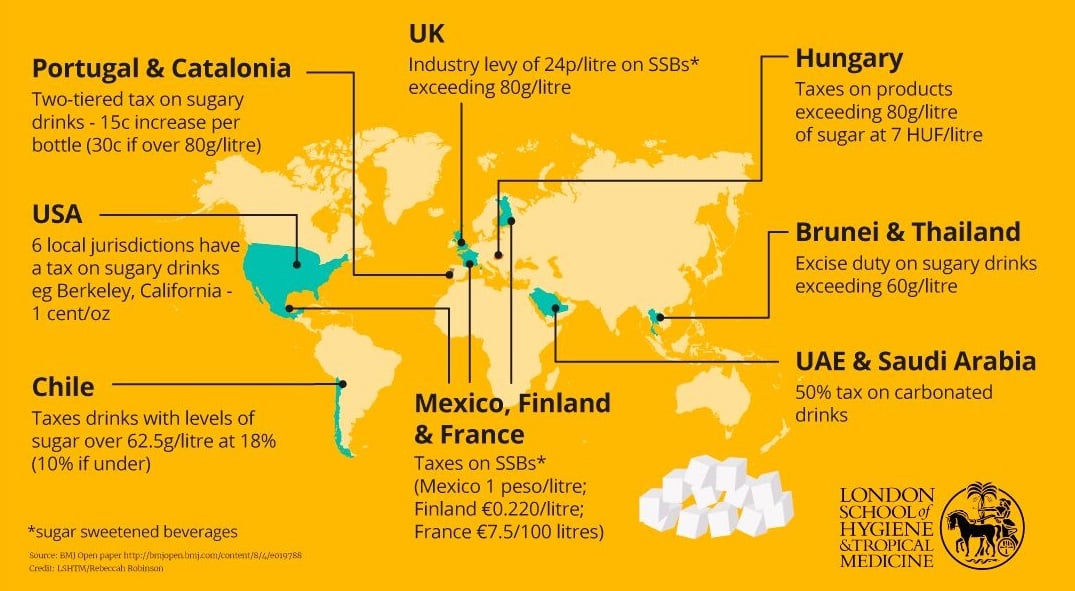

Countries around the world have introduced sugar taxes on drinks in different ways – directly to increase the cost of all sodas, or indirectly by prompting manufacturers and retailers to reformulate their products, reduce portion sizes or change product lines through the introduction of healthier alternatives.

There’s no global definition of what a high-sugar drink is – an indicator is the threshold at which taxes apply. The UK has opted for 8g of sugar per 100ml, while South Africa has chosen 4g.

The first sugar tax on soft drinks was implemented in Hungary in 2011, part of a wider tax on pre-packed sweetened products, salty snacks and condiments, followed by France in 2012, charging manufacturers the equivalent of an extra 6p per litre for any beverage containing added sugar or artificial sweeteners.

The most high-profile country has been Mexico, which uses the direct method. The country introduced its tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) in January 2014 to combat its huge obesity crisis – with more than 70% of the population overweight or obese. It placed one peso a litre on all SSBs, as well as an 8% tax on foods high in sugar, salt and fat.

This precedent was followed by Chile, Barbados and Berkeley, California in the US by 2015, and Mauritius and Belgium by 2016.

More recently, in 2017, Portugal and Catalonia, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Brunei and Thailand have introduced their own versions, followed by South Africa, and there are similar plans across a number of other countries.

In the UK, the system operates differently to most, as it aims to work indirectly. It has differential rates of tax according to how much sugar the drink contains, rather than a flat rate like Mexico. This offers a financial incentive for industry to reformulate their beverages to bring them below the threshold for the tax.

Fruit juice with high levels of natural sugar and drinks with 75% milk, and therefore high calcium content, are exempt.

The UK Treasury department, which originally estimated it would gain £500 million in revenue from the tax, has said that more than 50% of manufacturers have already changed their formulas to cut sugar and so will not need to pay the levy. These include Fanta, Ribena, Irn-Bru and Lucozade. The government now believes they will gain £240 million to the country’s coffers.

Manufacturers which have not reformulated certain products, such as Coke Classic and Original Pepsi, can absorb the tax or choose to pass it on to consumers. But the Treasury hopes that reformulation will be a continuing process.

Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury, Robert Jenrick MP, said: “More than half of all soft drinks have been reformulated to lower the sugar content, including many of the best known soft drinks. We hope that will continue in the months and years to come.”

Back in Tesco, shopper Sarah Gates, a finance administrator, has been looking out for price rises as her husband Cye and son Nathan, 16, are big fizzy drink fans. Luckily Cye’s favourite Dr Pepper has been reformulated – and now has 4.9 g of sugar per 100ml. “He hasn’t noticed any difference – there’s still some sugar in there, just not as much,” she says, standing outside her local One Stop convenience store.

But her son’s cans of Mega Monster Energy drink, with 11g of sugar per 100ml, (the can is 553 ml – so 55g of sugar, or 12 level teaspoons) have gone up from £1.75 to £1.90.

“I’ve tried to encourage him to have the blue-coloured sugar-free version but he still has the green one,” she says. “He has his own pocket money and the price is not going to bother him. If it’s available, he’s going to drink it.”

Sugar – not all things nice

The introduction of “sin taxes” reflects a sea change in established thought about the dangers in our diet.

For years, fat was seen as the biggest evil, but in recent decades the harms caused by excessive sugar, and its effect on non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as diabetes, heart attacks, stroke, liver failure and cancers have become increasingly evident.

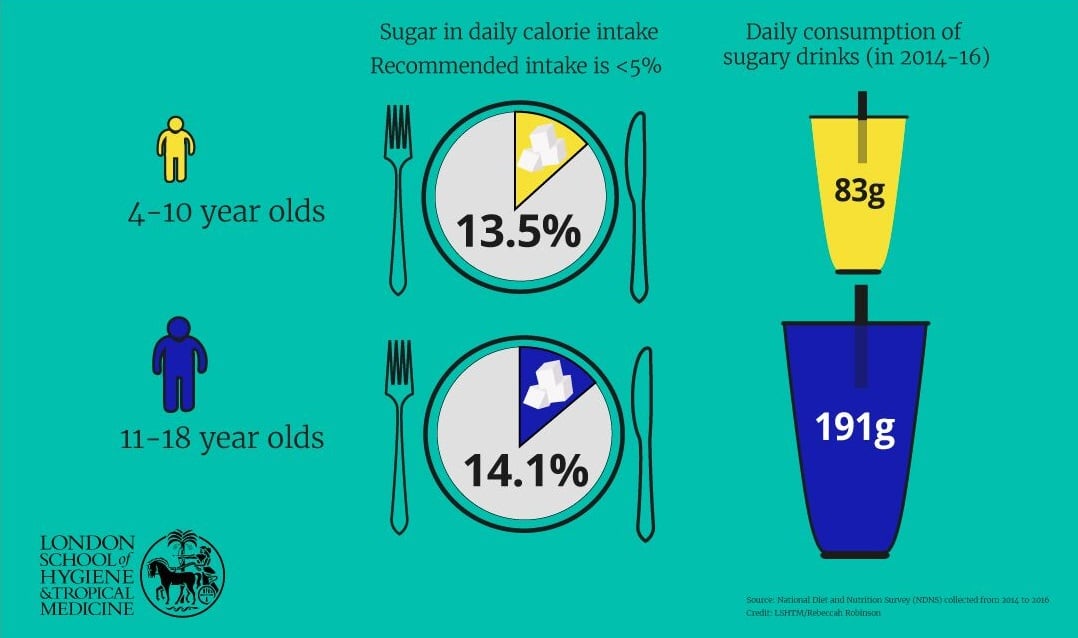

Public Health England has warned that adults and children over 11 should have no more than 30g of sugar a day, equivalent to 5% of our total calories.

There are two main issues with sugar, according to LSHTM alumnus Dr Modi Mwatsama, Director of Policy and Global Health, at the UK Health Forum, an alliance of organisations which produces evidence-based policy proposals to improve the public’s health and prevent NCDs.

Firstly, sugary calorie-dense foods, such as a small chocolate bar or a glass of fizzy drink, are easy to overconsume without realising, leading to weight gain and raising the risk of diabetes and heart disease. Sugar and calorie-dense foods are a problem because so much sugar is added to savoury products as well as sweet ones to make them more palatable.

Secondly, when we eat sugar, the bacteria in our mouths ferment it to produce acid which causes irreversible tooth decay. This affects both adults and children and has a knock-on effect on diet because chewing food becomes a problem.

An emerging area of research is looking into whether there is a direct metabolic effect of sugar, which makes it toxic independently of its health-damaging role through obesity. But this research is still in its early days and yet to be definitively proven, says Dr Mwatsama, who did her PhD on the evolution of UK public health nutrition policy from the 1980s to the 2000s at LSHTM.

Dr Harry Rutter, a senior clinical research fellow at LSHTM, and the deputy director of the Centre for Global Chronic Conditions, says sugar plays a role in excessive weight gain both in the developed and the developing world but it’s not the only issue.

“Sugar is one of many factors driving the obesity epidemic,” he says. “It’s far from the only thing to worry about. We need to see it as a factor within a wider system, and treat it as such.”

He cites a study in The Lancet by Boyd Swinburn and others which said that increasing fatness is the result of a normal response, by normal people, to an abnormal situation – the easy availability of cheap, processed food.

Writing in The Lancet himself, Prof Rutter said: “Supporting and encouraging people to respond more healthily to that abnormal situation is important, but the range of options within which people make their choices is skewed in favour of weight gain rather than weight loss.

“No approach will work alone, but changing the environments within which those decisions are made is likely to be far more effective than merely exhorting people to make better choices.”

Prof Rutter describes sugar taxation as an important example of what is known as a ‘Pigovian’ tax. “That’s a tax that aims to address the market failure brought about by products that cause harm (externalities) where the costs of those harms are not otherwise included in the price of the product (internalised),” he explains.

“It can be seen as a way to create a level playing field that removes the unfair advantage enjoyed by unhealthy products over healthy ones.” In England, the money raised by the levy will be spent on schools’ sports and breakfast clubs.

NCDs accounted for 72% of all global deaths in 2016, according to the World Health Organization. Developed economies have been hit hardest, but even in Africa NCDs, such as diabetes, heart attack and stroke, are predicted to become the biggest killers by 2030.

In the UK, 3.7 million people have diabetes, and every year 73,000 people die from coronary heart disease (CHD), and 40,000 people die from a stroke.

Sugar taxation around the world

Higher prices, better health

If taxation does work, the benefit could be immense.

A UK modelling study advocating a gradual reduction in the sugar content in sweetened beverages estimated that a 40% reduction in added sugars over five years would reduce the number of obese adults by roughly half a million and new cases of type 2 diabetes by around 300,000.

Sugar taxation has been described by Dr Cornelsen as a ‘defining economic intervention’ second only to previous measures to combat tobacco use.

In Mexico, in the first year of the tax’s introduction, Mexicans were buying 6% fewer sugary beverages than the previous 12 months initially, with the effects escalating as the year went on - declining by up to 12% by December 2014.

In the US, the first city to pass a soda tax was Berkeley, California, also in 2014. There was a 21% decrease in the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and a 63% increase in the consumption of water in the city's low-income neighbourhoods, according to a study published online in the American Journal of Public Health.

But it’s a complex picture.

One study found that the prices of drinks in Berkeley once the tax was introduced did not rise in line with the tax - on average 43% of the tax was passed on.

Dr Cornelsen and her team have been researching how people in the UK react to price changes in food and beverages to understand how interventions that target prices such as levies might work here.

She and colleagues do so by analysing large datasets containing thousands of UK household purchases from representative samples collected by Kantar Worldpanel, a consumer insight company which collects data on what people buy from a panel of 30,000 UK households.

Food prices vary from day to day and week to week depending on seasonal availability and price promotions, and the data reveals how households respond to the variations.

What Dr Cornelsen has discovered is that people tend to be more responsive to price increases than to decreases. This means that in relative terms, taxes may have a greater potential to change what people buy rather than subsidising healthier foods.

Specific to sugary drinks, the team has found that those on lower incomes tend to spend a greater share of their drinks expenditure on the sugary variety, but also that they tend to be more price-responsive, meaning a rise on cost will have a greater impact.

Other studies have shown that those who have high levels of sugar in the diet actually tend to be less price-responsive, compared with moderate consumers. Dr Cornelsen says: “Those studies suggest that it doesn’t mean that they won’t benefit from the tax, because even if their responsiveness is relatively lower, they might still have a sufficient change in their behaviours to trigger positive effects.”

Another subject that needs careful monitoring is the substitution effect - whether people substitute other products that have not gone up in price but may have similar amounts of sugar, to ‘make up’ for those that have, such as having a chocolate bar rather than a Coke, or a pure fruit juice which has high levels of naturally occurring sugars.

“Substitution might be working with the tax or against it. Because people’s preferences are varied, it brings in a lot of uncertainty,” says Dr Cornelsen. “It is really difficult to predict whether, even though we are buying fewer sugary drinks, that will actually mean that we will see health benefits.”

However, when price increases are combined with messages explaining the action, it appears the effect could be stronger, according to Dr Cornelsen.

A test-run with Jamie Oliver

She was part of a team that carried out a study using sales data from TV chef Jamie Oliver’s Jamie’s Italian restaurant chain in 2016.

The year before, sugary drinks in 37 of the restaurants across the UK were raised by just 10p, but prominent messages explaining why were also printed on the menu.

This 3.5% increase in price led to a 9.3% decrease in diners ordering these beverages. This ‘price responsiveness’ was three times higher than would be expected for sugary drinks purchases made from shops and supermarkets.

Dr Cornelsen believes that some of this effect could be because in the restaurants, the levy was very well-signalled on the menu, and highlighted on a Channel 4 documentary and in the press more widely.

“These drinks were separated, there was an explanation why the levy was being charged, and so there is the possibility that people are responding not just because there is a little increase in the price but they are responding to the message as well.”

Jenny Rosborough, a registered nutritionist and Head of Nutrition at the Jamie Oliver Group, said they were keen to get involved with the study to demonstrate the impact of a tax on nudging people towards choosing healthier drinks – with the aim of helping influence government policy.

The TV chef and restauranteur is vocal in his belief that we have too much sugar in our diets. He campaigned for the sugar tax and is an advocate for improving childhood diets, recently appearing before the UK’s Health and Social Care Committee discussing childhood obesity.

Dr Cornelsen said the study results suggest that notices with the reasons for the levy being introduced on sugary drinks should be well displayed in the drinks aisles in supermarkets permanently, which may nudge behaviour change more than the price increase alone.

“We need to make sure that these things don’t die out now after the tax has been implemented – so we don’t go back to business as usual.”

But Dr Mwatsama says the fact it’s not explicit to consumers is positive. “It’s in keeping with the ‘polluter pays’ principle that the manufacturers (as opposed to the consumers) pay - especially if the revenue raised is invested on measures to improve health.

“The ultimate aim is not to change the price of products; it is simply to encourage the manufacturers to reduce the sugar behind the scenes – reformulation by stealth. And if they don’t, then it’s for the manufacturers to pay the levy, not the consumer.”

From drinks to food

In research just published, Dr Cornelsen and others have found that introducing a similar tax on sugary snacks and confectionary in addition to beverages might make a huge difference.

In the first study of its kind, published in April, LSHTM Professor Richard Smith, working with Dr Cornelsen and others, found that extending fiscal policies to include sweet snacks could lead to larger public health benefits, both directly by reducing purchasing and therefore consumption of these foods, and indirectly by reducing demand for other snack foods and sweet drinks.

The researchers classified household expenditure on food and drink items in 2012-13 into 13 different groups and examined them in a national representative sample of around 32,000 UK homes.

The team found that on average people in Britain get 17.1g of sugar daily from sweet snacks they buy which is more than twice as much as they get on average from sugary drinks (6.9g).

As the demand for sweet snacks is as price responsive (a 10% increase in the price would reduce consumption by 7%), then higher price of chocolate, confectionery, cakes and biscuits may reduce sugar consumption more as we consume more of it in the first place.

As an observational study, it can’t explain why consumers may change their behaviour. But Professor Smith, Professor of Health System Economics at LSHTM, says: “This research suggests that taxing these sweet snacks could bring greater health gains and warrants detailed consideration.”

Dr Mwatsama agrees that while the study is a hypothetical economic study, it makes sense, particularly taking into account Hungary’s recent action to tax unhealthy food across the board, not just high-sugar drinks.

“You could argue that increased snacking, particularly salty snacks, makes you thirsty and makes you drink more liquids, and if your drinks of choice are sugary drinks, then your sugar consumption is going to go up,” she said. “That makes a good case for expanding the soft drinks levy in the UK to other sugary products.”

But it’s not just about taxing people.

Consensus reigns that in addressing obesity and other associated diseases, there should be a more varied approach in terms of policy, including dealing with aggressive price promotion and marketing, particularly towards children, and providing clear information on the nutritional content, as well as educating children, and also adults, to make healthy choices and be more active.

Working together on these, through collaborations between academics and others, may bear fruit.

Combating obesity through collaboration

It was in this spirit of collaboration that last year the Centre for Global Chronic Conditions was established at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, through a merger of two of LSHTM’s existing bodies: ECOHOST - The Centre for Health and Social Change, and the Centre for Global Non-Communicable Diseases.

Co-director Pablo Perel, an associate professor in the Department of Non-Communicable Diseases at LSHTM, believes that bringing expertise from different disciplines - economics, social political science, health science, health system expertise as well as epidemiology - will help solve some of the pressing issues in obesity, NCDs and other chronic conditions.

Obesity is a subject that many different groups at LSHTM are working on - some researchers are looking at epidemiological aspects, while others are investigating how frequent it is and what the different types of measurements for obesity are that would be valid in different settings.

Dr Perel, who is also senior science advisor to the World Heart Federation, says that one of the strengths of the Centre, like LSHTM in general, is that it has collaborators in Africa, India, and Latin America, who can enrich research on subjects like obesity which historically have been defined by following a European or high-income country population.

“Most people now acknowledge obesity is not something you can tackle individual by individual, but more from a society point of view,” he says. It’s about “defining how you can build healthier and non-obesogenic built environments, how we can make physical activities safer and reduce exposure to unhealthy food, particularly junk food and to vulnerable populations such as children.”

Urban planners worldwide are increasingly using the principles of active design to create environments which make it easier to walk, play sport and keep active to improve health.

Young people & sugar in the UK

The new tobacco

Back at the supermarket, consumers are still packing the fizzy drink aisles.

Ms Gates, who sticks to diet drinks herself, says the new tax is “similar to the tax on cigarettes”.

High taxation on tobacco has been used globally to both try and reduce consumption and raise revenue for the medical care needed to treat people with smoking related illnesses.

She says: “If we’re going to allow people to take part in harmful activities, we have to be prepared for the damage it causes on their bodies and the cost of putting them right. And I’m prepared to spend a few more pence because of that.

Dr Cornelsen admits that her work has made her think a lot about how much products cost and what’s in them. She still has the occasional fizzy drink, but hardly ever the sugary version and definitely not as every-day items.

She has reviewed evaluations of taxes on drinks and she says that before long, we will have an answer to whether the UK levy is effective. She is working with Prof Smith in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Cambridge and University of Oxford on an evaluation of the SDIL, described as ‘a major natural experimental evaluation study’.

The researchers are not just studying what happens to our consumption of sugary drinks and whether we switch to other products, but wider economic issues beyond health such as whether we are economically more productive and costs to the NHS.

She emphasises what has been repeated by many specialists: that the levy on sugary drinks is not a silver bullet to fix unhealthy diets. “While it is a step in the right direction, more needs to be done.”

We hope you enjoyed reading about our work in this feature. If you are interested in supporting projects like these and the many others we are leading to improve health worldwide, we would be delighted to hear from you. There are many ways you can make a gift to the School, from wherever you are in the world. Each and every gift we receive makes an impact, from funding scholarships, to updating our facilities or investing in new avenues of research. Whether it’s a gift of £5 or £500,000 your generosity will support our mission to improve health in the UK and around the world.