Graphic with human heads overlapping each other. Credit: Lightspring via Shutterstock

Brain Health Group

Understanding drivers of global brain health using diverse data

In the Brain Health research group, we aim to understand causes and consequences of poor brain health across populations using large health datasets to inform brain health promotion strategies.

Recent updates

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting.

Events

Newsletter

Contact us

We are a group of researchers working to understand the epidemiology of brain health conditions with a major focus on ageing populations worldwide. Maintaining brain health into older age is a key global health challenge. Over 20% of adults aged over 60 experience conditions that disrupt normal brain health and function; the most common are depression and dementia, affecting 7% and 5% of older individuals respectively.

Our research uses longitudinal electronic health records and multidimensional research cohorts from across settings (in the UK and internationally). We apply causal inference methods to these datasets to generate insights into the determinants and outcomes of brain health conditions. We work closely with collaborators including clinicians, public health professionals, epidemiologists, statisticians, and health data scientists. Ultimately, our research aims to inform public health approaches to improving brain health worldwide.

Plain English summary

People worldwide are living longer. Maintaining good brain health into older age is a major health challenge. 'Brain health’ refers to how well a person’s brain functions across areas such as cognition, emotion and movement. Good brain health enables people to live well and function in society. We study brain health in different populations around the world. Our research uses anonymous health data from GPs and hospitals. We also work with data from surveys and cohort studies to explore brain health across different groups of people. We seek advice from experts in medicine, public health, statistics and those with lived experience. Our research aims to identify ways to improve people’s brain health.

Resources

Recent updates

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting.

Events

Newsletter

Contact us

Charlotte

Warren-Gash

Clinical Professor of Epidemiology and Health Data Science

Kwabena

Asare

Research Fellow

Sharon

Cadogan

Research Fellow

Georgia

Gore-Langton

Research Fellow

Louis

Tunnicliffe

Research Assistant

Anne

Suffel

Research Fellow

Recent updates

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting.

Events

Newsletter

Contact us

According to the National Institute on Aging, ‘brain health’ refers to how well a person’s brain functions across several areas. Aspects of brain health include:

- Cognitive health — how well you think, learn, and remember

- Motor function — how well you make and control movements, including balance

- Emotional function — how well you interpret and respond to emotions

- Tactile function — how well you feel and respond to sensations of touch — including pressure, pain, and temperature

Brain health can be affected by age-related changes in the brain, injuries such as stroke or traumatic brain injury, mood disorders such as depression, substance use disorder or addiction, and diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Our principal areas of research are:

Acute infections and brain health in ageing populations

Through a Wellcome-funded programme of work, we are investigating relationships between a range of infections and different components of brain health in older age. Key questions include:

- What risks do acute infections pose to brain health in UK and US populations?

- Do relationships between infections and brain health differ in India or Mexico compared to the UK and US?

- What mediates relationships between infections and brain health?

Risk factors and complications of herpesviruses

We have conducted studies of the risk factors, burden, and complications of herpesviruses in large cohorts and health records datasets. These include:

- Quantifying acute complications associated with herpes zoster (shingles) including acute neurological, ocular, skin, and visceral complications

- Showing a lack of association between herpes zoster and either dementia or Parkinson’s disease

- Investigating risk factors for herpes zoster and herpes simplex virus type 1

Dementia risk factors and inequalities

Our work on better understanding population drivers of dementia includes:

- Investigating ethnic inequalities in dementia diagnoses

- Identifying factors affecting dementia risk among people with diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and stroke

- Assessing the validity of dementia diagnosis codes in electronic health records

Policy work on brain health promotion

We input into policy consultations relevant to brain health and work with initiatives such as Think Brain Health Global and organisations such as Alzheimer’s Research UK on brain health promotion activities. We also input into wider policy consultations on topics such as using health data for research.

Recent updates

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting.

Events

Newsletter

Contact us

See our selected recent publications below

Recent updates

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting.

Events

Newsletter

Contact us

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting. The review investigated the evidence for whether a broad range of infections are associated with telomere length or telomere attrition in adults. Telomeres are protective caps at the ends of our DNA, and their shortening is considered a sign of biological ageing. After screening over 8,000 studies and including 63 that met inclusion criteria, we found consistent evidence that HIV infection was linked to shorter telomeres. Findings for other infections such as herpesviruses and COVID-19 were mixed. However, many of the included studies had methodological limitations, leading to a high risk of bias. These results are relevant to brain health because accelerated ageing could increase vulnerability to age-related conditions like dementia. Building on this, our future research will use electronic health records to investigate whether accelerated biological ageing may help to explain a potential link between infections and dementia risk, while addressing the methodological limitations identified in previous studies.

Georgia presented some of the Brain Health group’s research at the Society for Social Medicine & Population Health 68th Annual Scientific meeting in Glasgow. The study investigated the association between nine infections, ranging from common infections such at urinary tract infections and diarrhoea, to less common infections such as malaria and tuberculosis, and the risk of each of impaired cognition, depression, and frailty, among adults in India. Using the Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) dataset, we found that people who reported having had at least one of the nine infections were at greater risk of depression and frailty than those not reporting an infection. Our results for impaired cognition were harder to interpret; we found that reporting an infection was associated with improved cognition when compared to those not reporting an infection. It seems plausible that people with impaired cognition under-report previous infections, leading to this counter-intuitive result. We stress the need for further studies using infection data confirmed either by a doctor or a laboratory test, rather than self-reported. We are hoping to publish the results of this study in a scientific journal soon. The conference was a great place to hear about research, in to brain health and other topics relevant to population health, and to engage in discussions around the strength and limitations of the methods used to answer public health research questions.

This summer, I had the incredible opportunity to complete an 8-week health data science internship at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) within the Faculty of Epidemiology and Public Health. As an undergraduate student in Neuroscience and Psychology, I initially thought my academic background might not align perfectly with health data science. However, through this experience, I have been fascinated by how a single dataset can be used to answer a myriad of questions which is something I previously explored within my research methods modules.

My project

During my time at LSHTM, I worked on a project examining the impact of indoor air pollution on cognitive function in older adults in India. The data came from Wave 1 of the Longitudinal Ageing Study in India (LASI). After identifying a research question, the next challenge was determining the most appropriate methods of analysis; This step-by-step process taught me how to approach a dataset logically, starting with exploration and ending with practical applications.

One of the most fascinating aspects of this project was uncovering trends even before formal analysis began. For example, when exploring the characteristics of our sample, we observed that as education levels increased, the proportion of individuals exposed to indoor air pollution decreased. Exploring these demographic characteristics not only guided our analytical approach but also helped us determine the relevance of our research question.

Regular meetings with my supervisors provided valuable insights into the collaborative nature of research and the importance of diverse perspectives. Their feedback challenged me to consider angles and ideas I had not initially thought of which enhanced my understanding of the research process.

By the end of the analysis, our results suggested that indoor air pollution had a protective effect on impaired cognition—a finding contrary to our expectations. Our findings highlighted the importance of critically evaluating how data is collected and analyzed, and approaching unexpected results with a healthy amount of skepticism.

Exploring career paths

Beyond my project, I had the privilege of meeting with various experts within the faculty and gaining valuable insights into what a career in epidemiology looks like. I also had the chance to attend meetings with the Brain Health Group, which was particularly exciting as a Neuroscience and Psychology student. Witnessing current brain health research in action deepened my appreciation for how interdisciplinary approaches are shaping the field. Initially, I viewed my studies in Neuroscience and Psychology as distinct from fields like public health and epidemiology. However, my time at LSHTM revealed how interconnected these disciplines are and how easily they can be combined.

Furthermore, I have gained increased confidence in using tools like RStudio for data analysis; This skill is highly relevant across various careers in public health, and I believe this internship has broadened the range of opportunities available to me in the future.

Final reflections

I thoroughly enjoyed my time at LSHTM. As well as enhancing my technical skills, I now have a clearer vision of my own career trajectory. The analytical skills, particularly with RStudio, and insights I gained at LSHTM have inspired me to explore opportunities where I can apply health data science techniques to research questions in brain health.

I am incredibly grateful to my supervisor, Charlotte Warren-Gash, as well as Georgia Gore-Langton, Kwabena Asare, and Kate Mansfield for their support throughout this project. Their dedication and expertise made this experience invaluable.

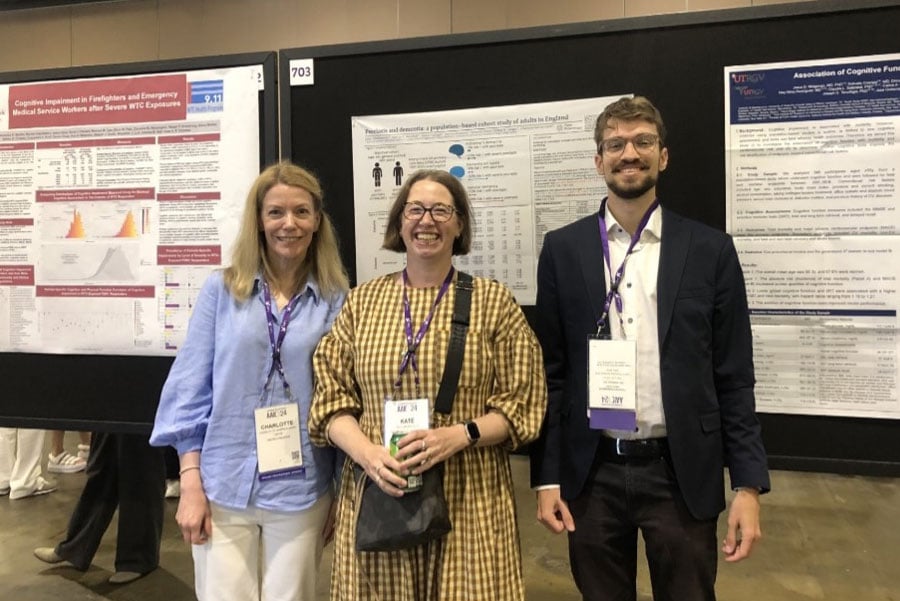

We presented some of our research at the Alzheimer’s Association International conference in Philadelphia. One of our studies investigated links between the skin condition psoriasis and risk of developing dementia. Using large health records data from a cohort of adults in England, we compared risks of dementia between people with and without psoriasis. We found that psoriasis was associated with an increased risk of all-cause dementia. The association was stronger for vascular dementia than for Alzheimer’s disease. We also found stronger associations in severe psoriasis compared to mild to moderate psoriasis.

We know that infections can affect the health of older adults in the short-term. However, we don’t fully understand long-term effects of infections on the brain. We studied the health of nearly one million adults in England aged 65 years or more. Using data from anonymous health records, we controlled for differences in factors such as age, sex, smoking and physical health. In our study, infections were linked to an increase in dementia cases. The more severe the infection, the higher the chance of developing dementia. Raised dementia risk persisted for more than 9 years after infections. We now need to find out more about why this happens and who is most at risk. Importantly, can preventing and treating infections help to preserve brain health?

Read the Washington Post article.

See the published paper.

Recent updates

Louis recently presented the findings of a systematic review in a poster at the British Geriatrics Society Spring Meeting.