Scientific research is crucial if we are to design the liveable, sustainable cities of the future.

The world is urbanising rapidly, with the number of city dwellers expected to rise to nearly 7 billion by 2050. People living in cities are already experiencing and will be increasingly exposed to the health impacts of climate change, from extreme heat and air pollution, to changing patterns of infectious diseases and food insecurity.

Some of the fastest growing cities in the US risk becoming unlivable due to rising temperatures. Cities in Pakistan saw record-breaking temperatures earlier this year, before becoming the epicentre of catastrophic floods that have claimed thousands of lives and the livelihoods of many more. Londoners sweltered in 40C heat while wildfires broke out across Europe.

Climate change is making extreme weather events in cities more frequent and intense. But climate-related risks can also be insidious, affecting us in ways we don’t necessarily see or feel at a specific moment in time. Air pollution linked to the burning of fossil fuels is a major cause of premature death and disease, with WHO’s modelling of air pollution data showing that almost every one of us living in cities today faces an increased risk of heart disease, stroke, lung disease, cancer and pneumonia.

People living in cities are on the frontline of climate change, but they are also coming up with solutions. As cities face growing challenges, researchers at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) are generating evidence to improve understanding of the intersection of climate change, cities and health. They are also are working with urban policymakers, communities, young people and a wide range of partners across sectors to find and implement the actions needed to create healthier, more sustainable cities of the future.

Health impacts of urban heat

People living in cities are particularly vulnerable to the health effects of extreme heat. This is because urban heat islands amplify exposure during the day and inhibit recovery at night.

A recent study led by LSHTM researchers and the University of Bern within the Multi-Country Multi-City (MCC) Collaborative Research Network showed that global warming is already responsible for more than a third of all heat-related deaths. The study, which used data from 732 locations in 43 countries, estimated that over a third of total heat-related deaths in London could be attributed to human-induced climate change, with the number reaching over half in Bangkok.

Another study led by the Environment and Health Modelling Lab at LSHTM, assessing temperature-related mortality in England and Wales between 2000 and 2019, showed that heat-related excess deaths were highest in London and other urban areas. The study provided detailed mapping of temperature-related deaths across the two countries, showing differences between cities as well as local variation within them.

“Our framework to map temperature-related mortality is useful for identifying high-risk areas and vulnerable groups, and can be applied to future scenarios. It’s important that urban policymakers and the general public have access to this kind of localised data, so they understand the risks and can act early to mitigate them.”

Dr Antonio Gasparrini, Professor of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, LSHTM

The animated map below shows heat-related mortality rate during the July heatwave in the UK:

The researchers used this framework to model excess deaths in the UK, including in London and areas within the city, during the heatwave in July 2022.

Mapping malaria hotspots to build urban resilience

Warming temperatures and rapid urbanisation are also changing the dynamics of the transmission of vector borne diseases such as malaria and dengue. This World Cities Day, the WHO has launched its first Global Framework for the Response to Malaria in Urban areas. While malaria predominantly affects populations living in rural areas, urbanisation in malaria-endemic countries is putting city dwellers at higher risk, particularly due to the expansion of unplanned settlements and potential for mosquitoes to exploit poorly managed urban environments.

Tackling climate-related threats, however, for example flood prevention and provision of clean water supplies, can have direct benefits for controlling mosquito-related diseases. In addition, as cities continue to develop, there is an opportunity to plan ahead and improve urban design to make cities more resilient to the threat of these diseases.

Mapping malaria risk in urban settings is a key strategy to understanding changing patterns of transmission and informing effective interventions such as improved housing and sanitation. A project led by LSHTM, the Ifakara Health Institute, the University of Copenhagen and the Royal Danish Academy plans to use algorithms to analyse drone surveys and satellite imagery, alongside data from household surveys, to identify potential malaria hotspots in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

The video below shows drone footage of Hananasif, an informal settlement in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (Credit: Johan Motelson):

“We’re using a combination of epidemiological research, technological innovation and community engagement to help tackle vector-borne disease risk in East Africa and provide tools to help ensure cities are designed to promote health, resilience and sustainability.”

Dr Lucy Tusting, Associate Professor at LSHTM and a contributor to the WHO Global Framework for Response to Malaria in Urban Areas

Malaria is one of many complex problems that cities are facing today in the context of climate change and urbanisation. This and other urban health challenges cannot be solved by the health sector alone. Different actors from government, academia, business and civil society need to be involved to ensure inclusive, secure and resilient sustainable urban health and development.

Connecting urban development with health and sustainability

There is no one-size-fits all for urban policymaking and for actions to be effective, they must be appropriate to the local context and coordinated across sectors, including energy provision, transport infrastructure, green infrastructure, water and sanitation, and housing.

The principle that urban policies should target the systems that connect urban development with health and sustainability underlies the Complex Urban Systems for Sustainability and Health (CUSSH) project, a research collaboration between six cities (London (UK), Rennes (France), Kisumu and Nairobi (Kenya), and Beijing and Ningbo (China), and 13 institutions including LSHTM and funded by the Wellcome Trust.

“A key insight that comes up time and again from our research is that urban solutions are co-dependent and interconnected and that achieving health and sustainability goals requires multi-sectoral action.”

Dr James Milner, Assistant Professor at LSHTM and CUSSH project researcher

For example, changes that shift a city’s energy supply from fossil fuel to low-carbon renewables may provide environmental benefits from reduced carbon emissions and improved air quality while simultaneously bringing health benefits, such as reduced premature cardio-respiratory deaths, as well as potentially fewer climate change-related health impacts in the future. In addition, integrated approaches are needed to prevent unintended adverse consequences, such as increased indoor air pollution as a result of insulating houses to make them more energy efficient.

Health co-benefits of climate action in cities

Children living in cities are among the most vulnerable to the health impacts of climate change, including through exposure to air pollution and extreme heat. As part of Children, Cities and Climate, LSHTM researchers modelled the child health benefits of reduced air pollution from decarbonising cities and the results were striking.

Across 16 global cities included in the analysis, improved air quality from achieving net zero emissions could prevent more than 20,000 cases of childhood asthma, over 43,000 premature births and over 22,000 low birthweight births annually.

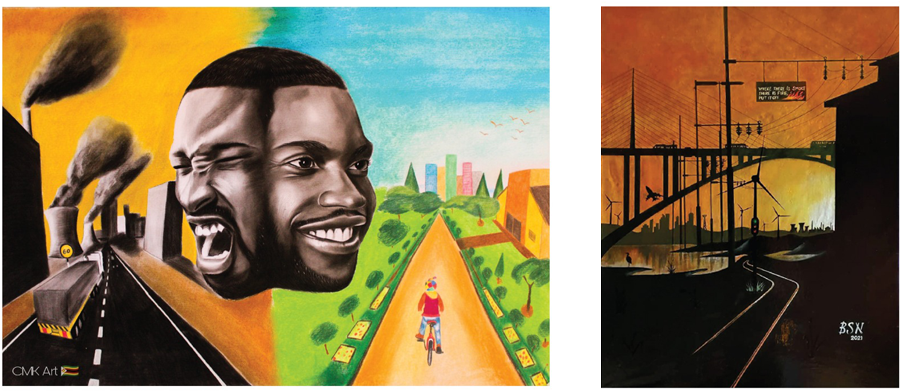

The researchers also surveyed over 3000 young people from 59 cities around the world to understand their views and found that four in ten young people surveyed saw air pollution as one of the three worst things about their city.

“Our research shows that many young people want to see action to make their cities more sustainable and healthy. They feel the effects of air pollution and heatwaves today, and want action now. They also have creative, ambitious ideas about how to address problems in their cities and improve their urban environments. I think it’s overdue that we listened to them!”

Dr Robert Hughes, Clinical Research Fellow at LSHTM and Principal Investigator of Children, Cities and Climate

Young parents are also worried about the impacts of heat and air pollution on the health of their children and have visions for a brighter future. Elizabeth, a 24 year old mother from the Muruku area of Nairobi, who took part in a co-design workshop coordinated by YLabs as part of Children, Cities and Climate, said: “When it is too hot you cannot be productive in either work or at school…but then you also cannot sleep at night and the babies cry without stop. The future I want for my child looks like this: There are trees along the roadside for fresh air and cool breezes, and the schools around also have trees planted everywhere so that my child grows up in a space he can thrive in.”

Finding pathways to healthy net zero cities of the future

Modelling studies have shown the potential for climate mitigation actions across sectors to save millions of lives annually through cleaner air, increased physical activity and healthier diets, as well as leading to cost savings from reduced health burdens. But we also need real-world examples to motivate change and inspire action.

The Pathfinder Initiative is gathering case studies of implemented climate solutions that are bringing many benefits to both people and the planet. The case studies, which will be included in the Lancet Pathfinder Commission report that will launch in early 2023, show that many effective actions are being implemented at the city level, from improving infrastructure for cycling and walking and promoting active travel in Buenos Aires and cities in New Zealand, to policies to reduce vehicle emissions and reduce air pollution in Tokyo.

There is also growing evidence of the health and climate benefits of nature based solutions, such as urban trees and more green space in cities. These benefits include reducing harmful air pollutants, encouraging more physical activity and improving mental health by providing access to nature. A recent study by LSHTM researchers showed that urban areas with more trees and vegetation had lower heat-related mortality and that the natural environment had a stronger effect than the built environment or socio-demographic factors.

“Evidence shows that urban greenspaces can bring many benefits to physical and mental health, but inequalities in access also need to be tackled to achieve the potential of these nature based solutions.”

Dr Peninah Murage, Assistant Professor of Environmental Epidemiology, LSHTM

Political leaders, organisations and citizens of cities are key actors for transformative change, where human health and environmental sustainability are addressed together through ambitious, integrative approaches. LSHTM researchers, in collaboration with partners around the world, are providing the scientific evidence and tools needed to ensure that urban policies and actions maximise benefits to health while accelerating the transition to zero carbon, sustainable cities of the future.