When Professor Joy Lawn was born 50 years ago it was against the odds.

The hospital she was born in was located in the remote district of Karamoja in the Uganda bush, close to the Kenyan border, and had no running water or electricity.

This region of Uganda was known as the punishment zone because it was such a hard place to live and work – no schools, little to buy in the shops, no decent roads. As a result, the area attracted few doctors and nurses.

Her mother, Norma, was a teacher-trainer married to a missionary and pregnant with her first child. She had been taken to the local hospital in labour.

It was a frightening time for a young woman; during the night the pregnant woman in the bed next to her in the maternity ward died from complications.

After struggling with contractions for some time, it was realised that her mother had an obstructed labour, meaning the baby could not be delivered naturally. The only way to save both their lives was to do an emergency Caesarean section.

But no one had been trained to perform one.

A general doctor at the hospital had previously observed the surgery and was called to help. He proceeded to cut her mother right down the front of her abdomen from her sternum down to her pubis, with just chloroform as an anaesthetic.

“Amazingly, I came out alive, not a stillbirth or a neonatal death,” said Prof Lawn . “My mum had a pretty rough ride post-op, but we both survived.”

Now Professor of Maternal, Reproductive and Child Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Prof Lawn believes that it wasn’t simply luck that meant that neither of them had died, it was the people around them that believed they shouldn’t.

Her mother’s midwife – a Scottish woman who by chance was working in the area – and her father Brian had held the medical staff to account.

“People shouted for my mother and that helped to save both her and me,” explained Prof Lawn. That was an unusual occurrence back then, but not so much today.

“That’s what changed for maternal deaths around Africa now … people say women shouldn’t die in labour,” she said. “However this attitude hasn’t changed for babies yet. People think it’s still normal for a stillbirth to occur, and they shouldn’t be talked about. Women are even blamed for their baby dying.”

A stillbirth is defined as a loss of pregnancy after 28 weeks and when this occurs, babies, as well as mothers, must be accounted for.

Prof Lawn believes that if you’ve got people around you who are saying stillbirths or neonatal deaths shouldn’t happen, either health workers or family members, “it challenges the norm of accepting these deaths of women and their babies.”

But any programme to reduce both neonatal deaths – children who die in the first 28 days of life – and stillbirths needs data to understand the size and nature of the problem. This was the challenge.

Sourcing the right data

As recently as a decade ago – until research done by Prof Lawn and colleagues was published – it was unknown just how many stillbirths happened globally because they were simply not counted.

Apart from the lack of a system to collect the data, the stigma about stillbirth was preventing people from talking about them, which was in turn impeding reporting.

This is what Prof Lawn made her mission — to collect this data on neonatal deaths by counting the numbers, causes, and how to reduce them, followed by the same data on stillbirths.

In 2005, she made serious headway.

Publishing her research in the Lancet Neonatal Survival series, she revealed the first national cause-of-death estimates in all 195 countries for the four million annual global neonatal deaths. Then in 2011 she published findings as part of the Lancet Stillbirth series, which included a systematic analysis of the first national and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates, undertaken with colleagues in the School and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Her figures were eye-opening.

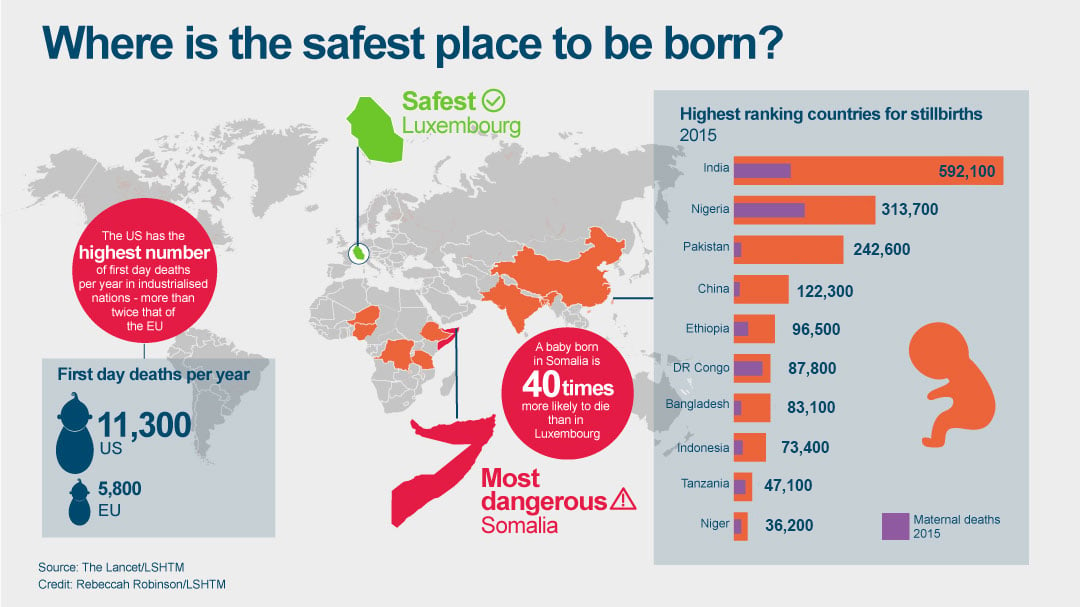

The calculations showed that there were 2.6 million stillbirths every year, almost all of which (98%) were in low and middle income countries. These included 1.3 million deaths where the babies had died in labour and most of which are preventable. Later research found that a further one million children die on their very first day of life.

Despite these alarming figures, it has taken years for stillbirths to get on the global health agenda as international health bodies prioritised infant deaths from malaria, lack of immunisations and diarrhoea. Neonatal deaths (now 2.7 million a year) were tackled next, though are still at an early stage today.

This lack of international attention is reflected in the annual reduction rates in deaths reported in 2016. Stillbirths are reducing by a rate of 2.0% every year, which is much slower than maternal (3.0%) or child deaths (4.5%).

At the current rates of progress, it will be more than 160 years before a pregnant woman in Africa has the same chance of her baby being born alive as a woman in a high-income country today.

“Newborns are still newborn on the global agenda. It’s only in 2014 that we got a plan endorsed by the UN that talks about what to do for them,” said Prof Lawn. “Stillbirths are still stillborn on the global agenda.”

Getting babies on the agenda

Thanks to the School’s work, the Millennium Development Goals had a push on neonatal deaths and a target was introduced in 2014. But the later Sustainable Development Goals, set in 2015, did not include a target for stillbirths, even though 157 countries had begun to collect data.

“People weren’t thinking about stillbirth in their research,” said Prof Lawn. “For example, most of the studies looking at malaria in pregnancy don’t measure stillbirth as an outcome. They look at the outcome for the woman and the birthweight of the baby, but not the death of the baby as a stillbirth.”

To the UN and others in the technical community, this was a blind spot.

To provide a route into this missing gap, Prof Lawn conducted the first global analysis of associated risk-factors. This would form part of the Lancet Ending Preventable Stillbirths series, which included a roadmap to eliminate these preventable deaths by 2030.

Her research found that the causes of death for neonates and stillbirths vary dramatically. The main causes of death for neonates are preterm birth (before 37 weeks gestation), infections and birth complications such as asphyxia, but for stillbirths it is malaria and syphilis.

Other causes include chronic conditions such as diabetes and obesity, which are now set to increase, potentially fuelling an increase.

But this can be tackled.

“In antenatal care all around the world, one of the things we do is measure blood pressure, but we sometimes completely fail to act on that; we don’t screen well for diabetes in pregnancy; with syphilis, where we could do the one stop testing and treat straightaway, we’re failing to do that,” said Prof Lawn.

She added that 1.3 million stillbirths that are also happening because we aren’t giving effective care during labour. “Stillbirth is not just one of those acts of God that was meant to be and you can’t do anything about it – people should be accountable,” she said.

India has the highest number of stillbirths globally, with almost 600,000 a year. This is mainly due to its population size. In terms of risk, Pakistan followed by Nigeria have the highest rates per number of pregnancies.

Two changes to behaviour that are vital to reduce deaths are women attending antenatal appointments and going to health centres once in labour where there is a skilled birth attendant to help them.

There are many reasons why women may not attend clinics, with different reasons in different places. It may be too difficult to get there, in areas with little transport options and long distances; in some places the care will cost the women more than they can afford. There are social pressures as well: in some societies ‘strong’ women are expected to be able to labour at home and in others male family members will forbid them to go. In some cases the women do not want to go, because the clinics are dirty and staff show them a lack of respect. For others, a previous experience of poor clinical care may put them off.

The list goes on.

The Rwandan example

In terms of reducing stillbirths, however, certain countries are ahead of the curve. One country at the forefront, and setting the example, is Rwanda.

Rwanda has reduced stillbirths the fastest of all of the African countries, cutting these types of death by 2.9% since 2000, due to increased coverage of care and more midwives.

The presence of a skilled attendant during childbirth in Rwanda increased from 31% to 69% from 2000 to 2010, a WHO report shows.

This rise in midwives has been complemented by the addition of 45,000 community health workers, 15,000 of whom are specifically tasked to encourage ante-natal care and take a woman in labour to a health facility.

As a result there has been improved registration of women coming earlier on in pregnancy. Commonly in other parts of Africa, such as Uganda, the median time for a woman to come in for antenatal care is in the third trimester. In Rwanda, it’s now early in the second trimester.

In addition, two-thirds of women are currently seen four times during their pregnancy, the recommended number of visits stipulated by the WHO until very recently.

Sophie Akimpaye is one of the people behind the success. As the Head Nurse at the Mushishiro Health Centre in the Muganga District in Rwanda, a centre that has won awards for mobilising expectant mothers through community health workers, she has played a vital role in bringing women in for care during pregnancy within her district

Mothers who attended the previous WHO–recommended four antenatal checks themselves were rewarded with gifts to encourage others.

Sister Sophie, 44, is one of three nurse-trained nuns at the 30-bed centre, which is run by the church diocese. She works with one other senior nurse, four midwives and six assistant nurses in lush green farming country, where the heavy rains produce deep red mud matching the red corrugated iron rooftops.

Part of the reason why more of her patients are increasingly engaged with health facilities is because of a new Government insurance system, Mutuelles de Santé, that is based on earnings. This means people are not worried about not being able to pay. The system includes pre-and post-natal care and more than 90% of the population were covered by 2010.

“Before the Mutuelles de Santé, we maybe only saw 50% of the population,” said Sister Sophie.

“I feel very happy because every patient who comes here is happy. If the case is too severe, we will take them to the district hospital by ambulance.”

The community health workers also use a text-based system that tells them when pregnant women should be seen at the health centre and reminds them when labour is a couple of weeks away, and what to do when contractions start. It also enables them to send ‘red-alert’ texts back in case of complications such as bleeding when they visit pregnant women.

The health centre is 55 km from the district hospital and three km from the main road making their antenatal achievements even more significant.

But now a new challenges awaits them.

In 2016, WHO antenatal care recommendations were updated to state that women should be seen at a clinic eight times, with five of those in the last trimester.

Dr Ӧzge Tunçalp , a WHO Scientist in the Maternal and Perinatal Health & Preventing Unsafe Abortion section, says the pregnant women should have their first contact in the first 12 weeks’ gestation, another two at week 20 and 26, then five contacts at 30, 34, 36, 38 and 40 weeks’ where the risks are higher.

While this will be easier to implement in certain countries than others, Dr Tunçalp believes Rwanda will be able to handle it. “Rwanda is an example where they had the political will and the will to implement and that combination really worked.” She said. “As a smaller country, they have the advantage of being able to really scale up certain interventions very fast and really be able to implement these things.”

Other countries, however, may fare less well, but Prof Lawn is determined to make their road as smooth as possible.

Over the next five years, Prof Lawn, who is also director of the School’s Centre for Maternal, Adolescent, Reproductive, and Child Health (MARCH) and her team aim to find more, and better data, on stillbirth causes and risk, how to reduce deaths through certain programmes, and create measures to be able to track the coverage of those programmes.

Her team will be working in Tanzania, Bangladesh and Nepal to observe an estimated 15,000 births, to collect data on the simplest possible measures of the care provided that can then be used more widely, to prevent babies dying.

Some of the interventions her team will be testing during and post-labour will be the use of resuscitation, antibiotics, ante-natal corticosteroids for preterm labour to help develop the babies’ lungs, and oxytocics to prevent haemorrhaging and the management of infections – none of which are routinely measured.

“If we look at the learning from the MDGs, the things that progressed the fastest weren’t just the things that had the most money, they also had good data for driving programme change,” says Prof Lawn. She says immunisation, ARV therapy for AIDS and the use of bed nets for malaria are three good examples where data on those interventions has been used to drive both coverage and the quality of care.

“In maternal and newborn health, it is known how many women give birth, but we have no idea how many, say, have (interventions) to prevent bleeding, or how many newborns are treated for serious infections” she said. “If we don’t have coverage statistics we have no idea how well we are doing. And we don’t have the measures of quality measures. it’s like driving a car with a blindfold”

Knowing what works to scale up

Another team at the School working towards improving maternal and child care in low and middle-income countries, are the IDEAS project, led by Professor Joanna Schellenberg, Professor of Epidemiology and International Health, and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Her team is working as a measurement, learning and evaluation partner to groups funded by the Foundation in north east Nigeria, Ethiopia, and both West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh in India where there are particularly high maternal, newborn and child death rates.

Importantly, the IDEAS team are measuring the effectiveness of something that is greatly needed, but extremely difficult to achieve: behaviour change. They’re measuring whether changes in behaviour that improve newborn health are actually happening, such as a mother giving birth in hospital and immediately breastfeeding.

“In the past, some groups have been focused on spending large resources to measure survival every five years, two years, one year, but what’s important is tracking whether the things that would lead to better survival have changed,” said Prof Schellenberg.

Can we prevent women dying after childbirth?

The project began in 2010 and since then the team has carried out a series of large, representative household and linked health facility surveys, to measure interventions such as whether women give birth in healthcare settings, but also whether those facilities are providing the appropriate standard of care.

One key finding to date is that in Ethiopia, there has been a dramatic shift towards women giving birth in health facilities. IDEAS surveys showed a rise from 15% women in 2012 to 43% in 2015, an increase of 28 percentage points which is unusual. She puts this success down to an ‘enabling environment’ assisted by Government leadership and buy-in, Gates’ funding, and a number of other factors.

While that is very positive, according to Professor Joanna Schellenberg, it’s important that the health facility has not only a skilled birth attendant, but also the ability to carry out live-saving actions.

“One of the principal killers of women in childbirth is haemorrhage,” she explains. “Just giving birth in a health facility isn’t going to change anything unless that health facility can provide things like blood transfusion in a woman who’s potentially bleeding to death, or potentially use a preventive approach to manage the third stage of labour.”

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) – defined as the loss of 500 ml or more of blood in the first 24 hours of giving birth — can be prevented using prophylactic uterotonics, which contract the uterus and seal blood vessels. Results from IDEAS surveys show that their use rose from 11% in 2012 to 35% in 2015.

To her, success means that the findings are used to change what people do on the ground. “It means that the Gates’ Foundation would be using our results in their decisions. To some extent this is already happening.”

New uses for old drugs

Haleema Shakur, Co-Director of the Clinical Trials Unit at the School, is also tackling the issue of postpartum haemorrhage, by trialling a new treatment called tranexamic acid (TXA), which showed great promise in earlier trials.

TXA, a blood-clot stabiliser or antifibrinolytic, was first discovered by Japanese researchers in the 1950s — husband and wife team Shosuke and Utako Okamoto.

“The dream for the wife was to find a treatment that could help with stopping women bleeding to death, but she really couldn’t convince the obstetricians in Japan to actually follow through and do the research that was needed,” said Ms Shakur, Associate Professor at the Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health.

Since then, doctors have tested TXA in surgical situations and in 2004 a review showed the compound reduced the need for blood transfusions by as much as a third.

Ms Shakur and colleague Professor Ian Roberts used this evidence to study bleeding following trauma injuries such as car crashes and shootings in Nigeria, known as the CRASH2 trial, and found that the drug again reduced bleeding by a third — if given in the first hour.

“If you have a woman in front of you in a hospital bleeding, and if you can reduce her chances of dying, that’s worthwhile”

Ms Haleema Shakur, Associate Professor and CTU Co-Director at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

But the game-changer came thanks to staff at the hospitals in Nigeria. They repeatedly asked Ms Shakur and her team why they weren’t looking at young women who were commonly being admitted as emergencies having almost bled to death after giving birth at home.

Ms Shakur learned that every year about 14 million mothers develop this severe bleeding after childbirth globally; about 1% of them will die, within an average of 2-4 hours from the start of bleeding.

This realisation soon led to the WOMAN trial – the largest trial on TXA to date – in 2010 which recruited 20,600 women in 193 hospitals in 21 countries to investigate whether TXA use could reduce death and hysterectomy during childbirth.

The results, due to be published early next year, are being awaited keenly as incidence of PPH is increasing globally, even in countries like the UK, where the rate is currently 5%. In Nigeria it is double that.

It’s not going to be a magic bullet entirely, because there isn’t one single thing you can do to cure this, and it’s not addressing all the other issues faced by women.” said Ms Shakur.

“But if you have a woman in front of you in a hospital bleeding, and if you can reduce her chances of dying, that’s worthwhile.”

Making enough time for care

The need for care, however, does not end after a successful childbirth. There are many more stages of care after this point. For example, there is great variability worldwide in the length of stay for a mother in a health facility.

Research by Oona Campbell, Professor of Epidemiology and Reproductive Health at the School, found that the mean stay after women give birth to a single baby ranged from 0.5 days in Egypt, to 6.2 days in Ukraine. In Africa, Zambia had the shortest average stay (1.1) compared with 2.6 for Benin.

The problem is that women may be pressured to leave too early because of the need for beds, however, Prof Campbell adds that longer stays do not necessarily mean better care. She warns that women may be kept in hospitals until bills for care are paid, rather than them actually receiving additional services.

Prof Campbell now plans to look at why these variations occur.

“The moment of childbirth and the few hours afterwards are probably the highest risk period, but risk continues in the first couple of days of life,” she said. “You want those women who are having problems that have taken all that trouble to come in to health facilities, that those problems are detected.”

Another factor is making sure mothers are confident when they leave the comforts of the hospital.

“You’d want them to get help establishing breast feeding and making sure that they’re confident and comfortable looking after their babies,” said Prof Campbell.

This confidence is vital given this may be many young women’s first experience of health services. She concludes: “If they’re treated really poorly, what do we expect from them in the future in terms of coming back for care for their children or other health issues? It’s a critical period of transition.”

The recent Lancet Maternal Health series, led by Prof Campbell, showed how too many women experience one of two extremes: where they either receive care that is not timely or sufficient, or they receive too much care, too soon. The latter is marked by over-medicalisation and excessive use of unnecessary interventions in healthcare services. Meanwhile, some women receive no care at all.

The series called for a five point agenda for change to improve this situation, the first of which was quite straightforward: good quality care for every woman, every newborn, everywhere.

In her work Prof Campbell has seen many births in the UK and other rich countries and believes the commonality between them all is good care, whether things go wrong or not. “Sometimes it looks like an amazing process where even if things go wrong, women are treated really well, kindly, and are supported and you think, ‘Wow.’ I want that for every woman.”

The need for such aftercare is exemplified by Prof Lawn’s tale of her own birth in Uganda, half a century ago.

Her mother had experienced an unusually short stay in hospital, despite having had an emergency caesarean. She had been sent home the day after the procedure, and the birth of her first child, on a mattress laid on the back of a Land Rover.

Once home, she suffered a potentially fatal post-delivery complication of sepsis, blood poisoning, but thankfully survived.

She went on to have two more children in Uganda but Prof Lawn’s father had made sure her mother’s next two pregnancies were less traumatic. “My father packed my mother off to a maternity waiting home in the capital Kampala about five weeks before the due date,” she remembered. “Even then, she had a post-partum haemorrhage due to a retained placenta during the last delivery.”

Her case demonstrates that whoever you are, wherever you are, and whoever is shouting for you, childbirth comes with high risk, but these risks can be reduced with the right resources and attitudes.

“My mum is a remarkable woman,” said Prof Lawn . “She survived – and I also survived – because people had a norm that we should survive.”

Now the goal is to make that the norm in every clinic – in every country.

Title and cover image:© Save the Children