Imagine if one day something changed that would completely alter the way you live your life, day in, day out, through no choice of your own. It determines where you go, who you see, what you do — and none of it is within your control.

Take it one step further and envision a situation that created a new way of life not just for you, but also for your entire society, and denial would only make it worse. If you — or anyone else — didn’t listen, you or your loved ones could be affected and at worst, die.

This may sound like some form of military dictatorship, but the villain in this scenario is not a human, but rather a miniscule particle unseen by the naked eye. The scenario is not uncommon: it’s the harsh reality of an infectious disease outbreak.

Just one infected person is all it takes in today’s increasingly globalised world to harbour, and spread, a minute pathogen against which you, and your entire population, have no means of protection. What soon follows is struggle, confusion and panic as people fear being wiped out from the world they know and love in an instant.

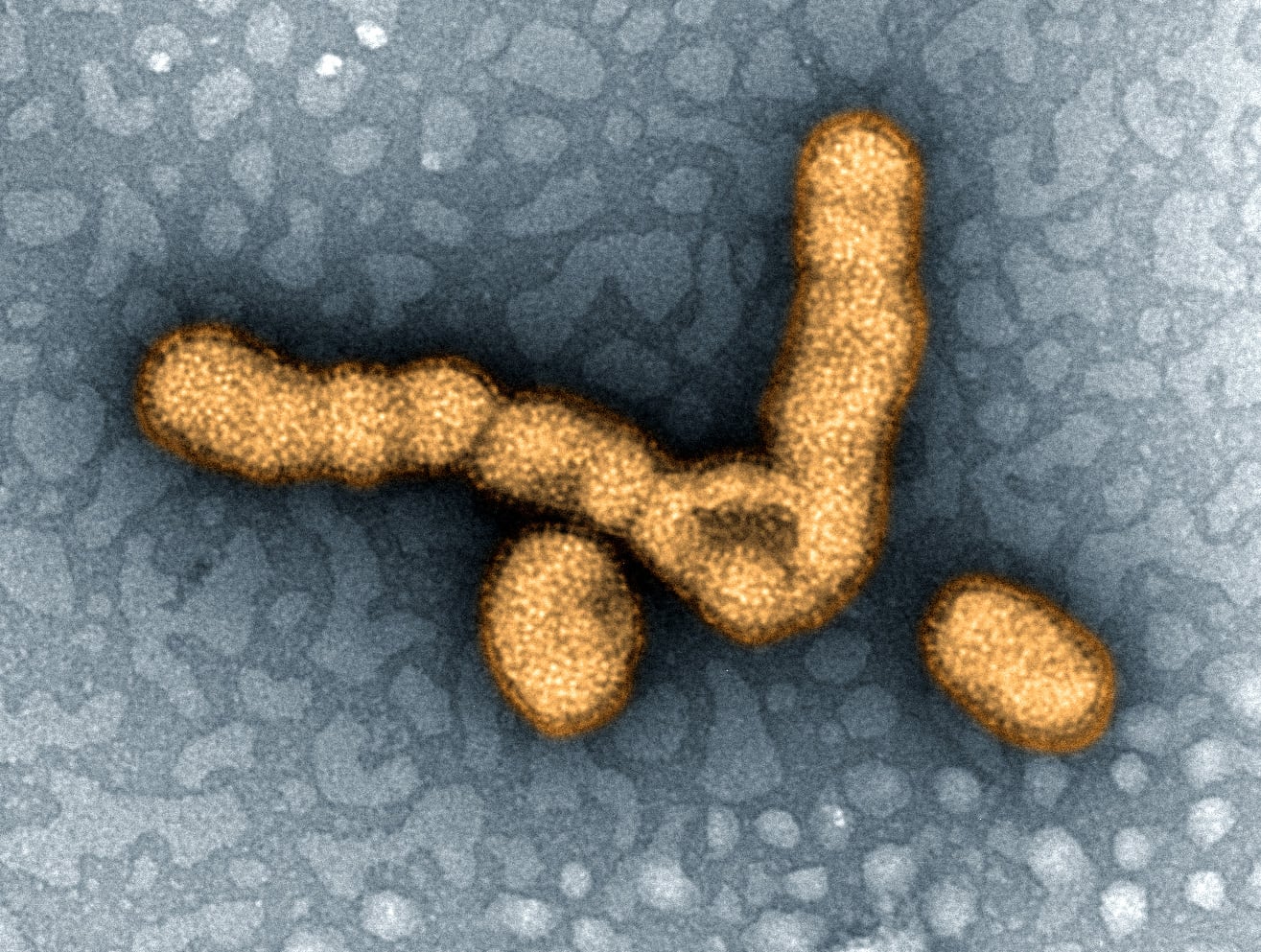

The culprit is most commonly a virus.

Recent examples include SARS and the H1N1 influenza, where people across countries and continents had to question the air, and people, surrounding them. A simple cough would echo a ripple of panic amongst anyone standing nearby.

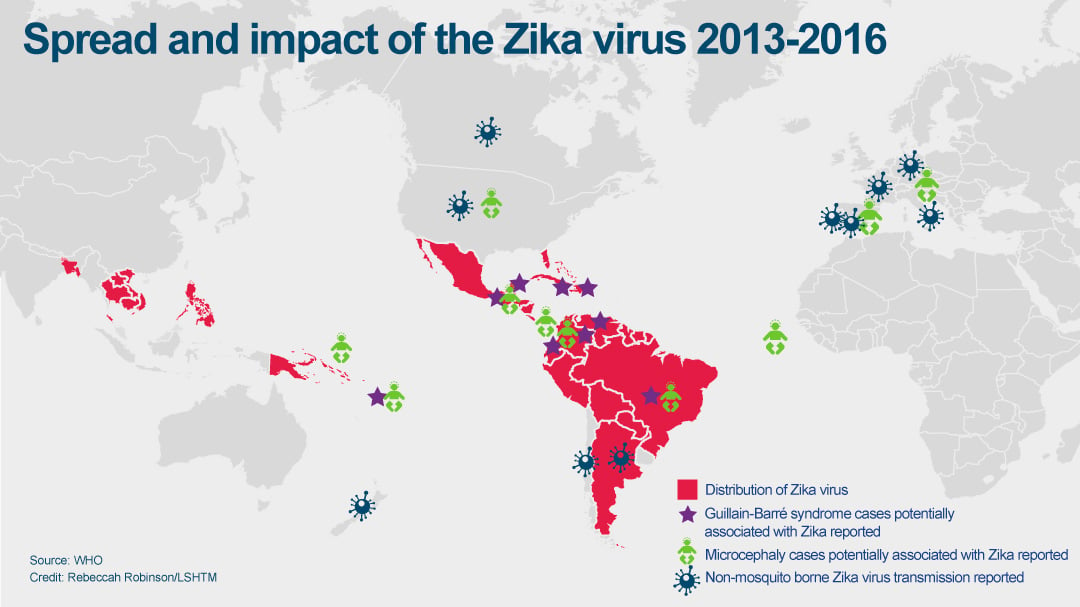

Right now, people — notably women — across more than 65 countries are living in fear of the Aedes mosquito that, along with multiple other viruses, is harbouring the once unacknowledged Zika virus. They dread what it may do to their future child.

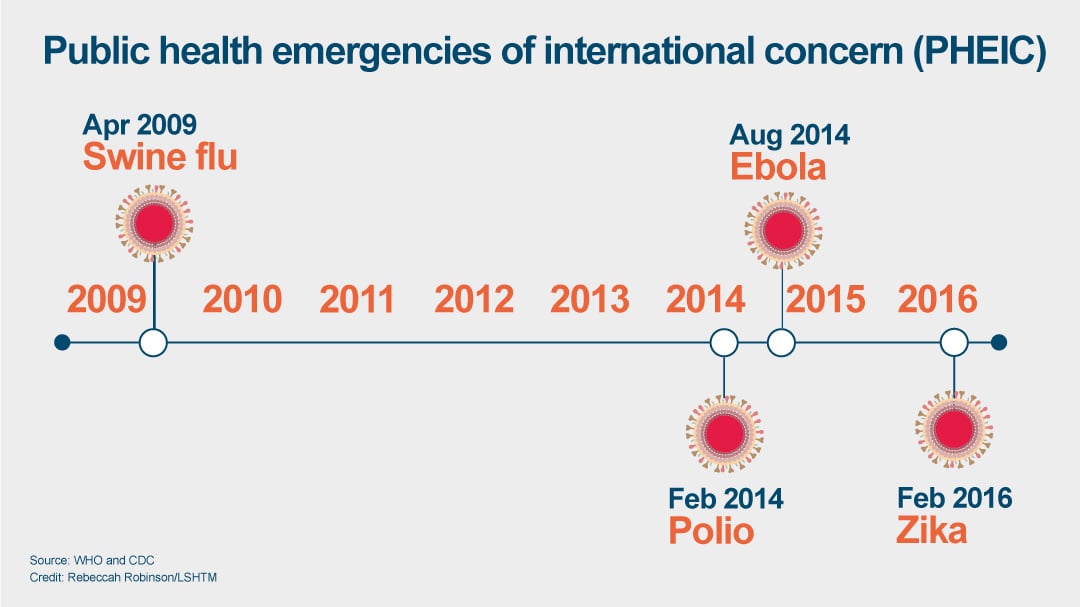

These outbreaks, except SARS, became public health emergencies of International Concern (PHEIC) — defined as extraordinary events that constitute a public health risk to other states and have potential to require a coordinated international response. On their arrival, societies changed in an instant.

”It’s the unexpected nature,” says Professor Jimmy Whitworth, Professor of International Public Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. His work focuses on improving research conducted during outbreaks to inform future emergencies. To date, the evidence used to inform responses is extremely limited.

“The evidence base generally is very weak and that’s because this is difficult research to do,” he says. The first step in any outbreak is establishing strong leadership and delivery of an effective response to control the situation as quickly as possible. Under the leadership of Professor Peter Piot, the School has played a prominent role in such responses, including H1N1 and now Zika, harnessing his decades of experience in both outbreak control and advising governments. But now entering the arena as an increasing priority is the need for good evidence. “We can do better in terms of responding by doing research much more rapidly during outbreaks,” said Prof Whitworth.

Learning from Ebola

There have been four PHEICs to date, one of which was the 2014 Ebola outbreak. Though predominantly limited to the region of West Africa, the severity of the disease and news of its more widespread transmission caused panic across the world.

The arrival of the virus in the West African countries of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in March 2014 changed the nature of these populations. It took away their intimacy and blocked their traditional experiences of human touch, forcing them to instead build walls between loved ones. Each person became their own enclosed vessel through which they witnessed hundreds of people drop in front of their eyes from something they had never heard of before. They saw sudden fever, vomiting, and sometimes bleeding from various orifices without real insight as to why this was happening — at least at first.

They were told it was called Ebola, but it bared no memory to them, so all that could follow suit was fear of this unknown villain. The virus used any ignorance among the population to thrive.

“At the very beginning of the outbreak there was panic,” recalls Dr James Soka Moses, a Liberian clinician and current Master’s student at the School.

Dr Moses survived more than one year working in Redemption Hospital in Monrovia, his country’s capital, where he helped treat over 600 Ebola cases during the 2014 outbreak. He witnessed a lot of panic, even amongst his staff.

“People didn’t know how to protect themselves,” says Dr Moses. “When a nurse became infected and died, the hospital became empty.” He remembers health workers desperately needing information to help them return to work without fear. The effect outside of his hospital walls was even greater.

“When there were so many deaths. That caused a lot of confusion, and panic. Infected patients and contacts started to run to different communities and with them they took the infection and infected more people.”

This became the largest Ebola outbreak ever known. “In the end, we had thousands of contacts in communities,” said Dr Moses.

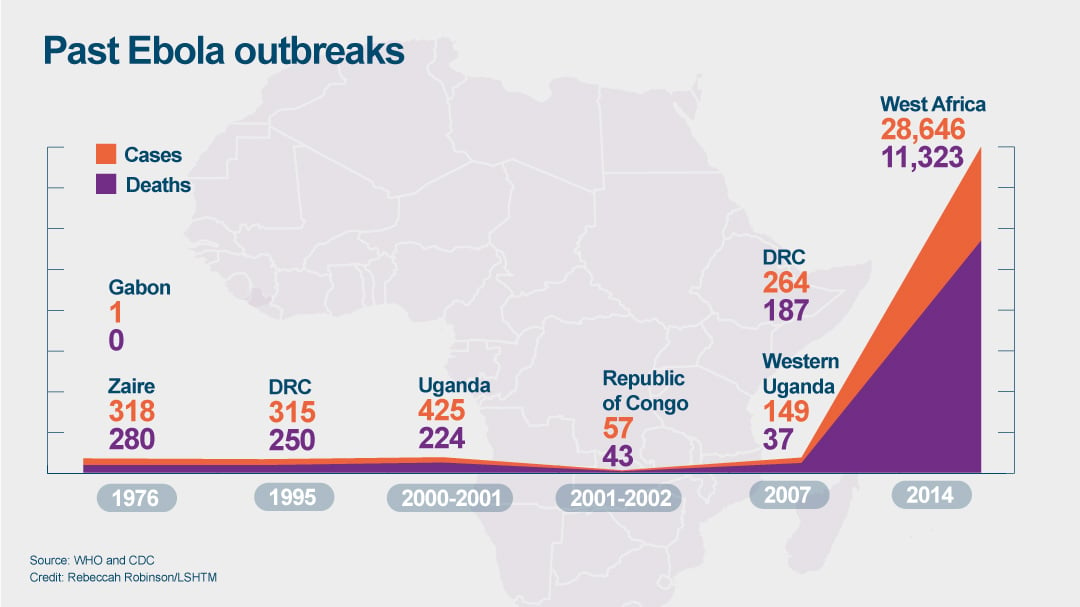

Lasting over two years, the West African Ebola outbreak infected more than 10,000 people in Liberia alone and caused almost 5,000 deaths there. Overall, the region saw more than 28,000 infected, as the virus spread rapidly across neighbouring borders and killed over 11,000 people.

When the virus arrived on this fresh soil, already weakened health systems and unstable countries recovering from over a decade of conflict meant all barriers were down.

“If Ebola had been identified and control measures put in place within a few weeks, it would have been eminently controllable with standard public health measures,” says Prof Whitworth. Swift control was the case for other Ebola outbreaks that took place in different regions of Africa since the first recorded cases in 1976, and even a separate outbreak in 2014 in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“In West Africa, we came pretty close to the brink of national collapse and of countries actually disintegrating.”

But the region made it through.

Despite criticism of a slow global response, the virus eventually came under control thanks to a range of policy, scientific, and community measures put in place. Experts at the School, including Professor David Heymann, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology, aided this response.

“Early on through the School we were active in promoting the research necessary,” said Prof Heymann who co-chaired the World Health Organization (WHO) director general’s advisory group on the Ebola response.

Along with other experts, he shared knowledge on what was needed to bring the outbreak under control, including the Ebola-Tx trial, which tested the potential of convalescent plasma from Ebola survivors to treat infected people.

Researchers at the School also provided insight into the state and progression of the epidemic in order to plan the necessary scale of response. Modelling studies helped highlight the scale of the outbreak and the fact that more resources were needed, and quickly, including how many cases could be expected and how many beds would therefore be needed.

“One of the things that galvanised the international response to Ebola was simple modelling working out what would happen with this epidemic if nothing was done about it,” said Prof Whitworth.

Another pivotal aide was the fast-tracking and testing of vaccines already in development. The VSV-EBOV vaccine, developed by a broad partnership of external organisations, was tested during the outbreak and was found to be effective. The vaccine helped control the outbreak using ring vaccination approaches, designed by Professor John Edmunds at the School, where all suspected people were immunised. Prof Edmunds received an OBE for his services to infectious disease control, in part due to his work on this outbreak, and this vaccine trial was a success, but its long-term protective ability to protect entire populations, however, is unknown.

Teams at the School are currently working as part of the EBOVAC global consortia of leading health organisations to conduct trials of a prime-boost two-dose candidate vaccine regimen, which could provide this prolonged protection against the Ebola virus and prevent further epidemics on this scale.

But for Prof Heymann there was one key priority he wanted to stress. “I pressed upon everyone that though clinical trials were important, the most important action was to empower communities with understanding as to how to stop the outbreak,” he said.

Empowering those most affected

Prof Heymann worked on the first reported Ebola outbreak response in 1976 and ones that then followed in 1977 and 1995. As the lead for emerging infections at WHO, he has advised on multiple outbreaks since and remembers the difference that can be made simply by talking to communities in a language they understand. Alongside Dr Jean-Jacques Muyembe, Director-General of the Democratic Republic of the Congo National Institute for Biomedical Research, he entered affected villages where Dr Muyembe would primarily speak with village leaders to explain what Ebola was, how it spread and how others can become infected in close proximity. Word then spread naturally among those at risk.

“By using language that they could understand he was able to get communities to work very rapidly to stop transmission,” said Prof Heymann, who feels this was not the initial priority in West Africa. “We’re too biomedical in all our approaches, but we’ve learned that community engagement is the key as we’ve gone along.”

Without communities on board, any control measures become somewhat redundant. After all, extra hospital beds and safe burial practices need people to use them, and follow them.

“If communities can be empowered with understanding about how to bury their own people safely and how to prevent themselves getting infected, outbreaks can be stopped,” said Prof Heymann. “That’s how they‘ve been stopped in the past and will be stopped in the future.”

Dr Moses saw the difference this made first-hand on his wards in Monrovia, not just among the public, but also his staff at the hospital. People learned to understand that they needed to keep a distance from each other, avoid physical contact, wash their hands and check their temperature at regular intervals, and pass this knowledge on to everyone around them. Seven members of his team were infected, but from a total of 250.

“The biggest impact came from the communities themselves, the community support,” he said. “Communities encouraged sick people to come for treatment, to identify contacts, to support them and encourage quarantine and maintaining their own forms of surveillance.” This was in stark contrast to the early days of the epidemic, where people fought health workers, went into hiding and would conduct secret burial ceremonies where people would come in contact with bodies of those who had died from the disease — and remained infectious.

“That support from the community made controlling the outbreak a lot easier for us,” he said.

A fellow advocate of this mantra of community engagement is Dr Heidi Larson, an Associate Professor and anthropologist at the School. Her research focuses on social, cultural and political factors that influence the acceptance of health interventions, such as vaccines, and uses communications approaches to improve knowledge among certain communities.

“Communication can’t fix a problem you don’t understand.”

In order to understand why people, and communities, may have resistance to certain health interventions, she believes in talking, and more importantly listening, to them regularly, rather than force-feeding them information from above. “You need to have some continual listening mechanism,” she said. “I can’t understate the importance of a conversation.”

Prof Whitworth agrees. “A lot of what was being said to communities was ‘don’t do this, don’t do that, don’t do the other’ without any real guidance on what they should do instead,” he said. “That fed back to help refine the public health messages coming out.”

After years of experience across a range of communities in Nigeria, Pakistan, Sierra Leone and other countries, Dr Larson has narrowed down some of the core reasons why people can be resistant to a health intervention. They include religion, distrust of providers or bad experiences at health centres, concern around the safety of a product and most often, social marginalisation. “The dominant driver [can be] marginalised groups with low access to services,” she said.

These drivers are commonplace for example in Sierra Leone, the country hardest-hit by Ebola, with over 14,000 infected. Now, as part of a consortium including Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson and Johnson, Dr Larson is working with communities in the Kambia district of the country as part of the EBODAC study to improve acceptance and uptake of their EBOVAC Ebola vaccine which is being trialled there. The study forms part of the Ebola vaccine projects, funded under the IMI Ebola+ program, which was launched in response to the Ebola Virus Disease outbreak.

The power of rumour

Through her previous work on the polio eradication program, Dr Larson saw the power that rumours and poor communication can have on the demand for vaccines. Resurgence was seen globally in the number of cases of polio in 2014 where 60% of cases reported were a result of international spread. This “extraordinary” event was enough to declare it a PHEIC.

A decade prior to this, communities in some countries heard rumours which impeded progress of immunisation campaigns, namely in India and northern Nigeria.

“[In 2003] there was a major boycott of the polio vaccination programme in northern Nigeria that took nearly 11 months to resolve,” said Dr Larson, who worked to control a similar event in Uttar Pradesh, India, the year before.

“Both were in lowest health and education indicators, history of marginalisation, a lot of strong religious beliefs,” she said. “And both came out with rumours, anxieties and had aggression towards health workers.” Seeing these as key drivers for new rumours, she wants future situations to be anticipated and prevented, using research.

“We can do all we want globally, but the fact remains that if countries are able to stop infectious diseases more rapidly, everyone benefits.”

Professor David Heymann, Professor of Infectious Disease at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Rumours have arrived on site in Kambia at the EBOVAC trial, where people have raised concerns over the provision of health insurance for trial participants. Through conversations, the local listening teams soon discovered people fear that such a benefit is only provided because things will go wrong. “We call this researching the ecology of rumour,” says Dr Larson. Messages being delivered had to be corrected in order to remove anxiety.

Regular rumours her team faces are those associated with blood samples taken during trials. “There are rumours of blood stealing and what are you doing with it,” she said. “But some groups have much bigger anxieties than others.”

When it comes to disease control in any part of the world, regardless of the disease, the community, the epidemic, or society, one key word is constantly brought up as a barrier to effective control — stigma.

“Stigma is a human trait that is not one of our best features as a human race, but there’s quite a bit of it in different settings,” says Dr Larson. The stigma of Ebola remains in West Africa today, where people who have fought and survived infection, or helped treat those infected, see themselves being ostracised from their society.

Dr Moses experienced this during his time at Redemption Hospital. “I barely escaped infection…many other colleagues became infected. So as a contact no one wanted to interact with you,” he said. “To make it even more challenging, I had to stay away from my children…from family, to keep them safe also.”

There are now over 10,000 Ebola survivors in the world, according to the WHO.

Moving on to a new outbreak

National leadership, international guidance and community empowerment brought Ebola numbers down to where they are today — with just 13 newly infected people in West Africa as of April 2016. The outbreak was no longer considered an emergency as of 29 March 2016.

But as the world sees Ebola less frequently on their news channels, word of another epidemic inciting international concern has sharply risen in another region of the world — Latin America.

The five letters of Ebola have quickly dissolved into the four letters of a very different virus: Zika. This newcomer has much lower severity in terms of its symptoms and a different means of transmission, but its impact on newborns has stirred international concern.

“We’ve never seen anything like this before,” said Prof Whitworth. “The really worrying situation is what is happening with pregnant women and what happens to their babies.”

Zika virus is spread through the bite of the Aedeas mosquito, found in many regions of the world, including Brazil. The current outbreak began in French Polynesia in 2013 after which it spread to Bangladesh, the Cook Islands and New Caledonia before arriving in Brazil in February 2015. The virus has now spread to at least 65 countries, including the United States, but the greatest number of cases remain in Brazil.

There is currently no treatment or vaccine available, however these are now in development by multiple organisations and institutions worldwide.

Babies born to mothers infected with Zika during their pregnancy are at risk of microcephaly — a smaller head associated with incomplete brain development — and other neurological problems. The numbers of microcephaly cases suspected to be linked to Zika in Brazil are staggering, now over 1,700.

These consequences of infection are why the outbreak was declared a PHEIC in February 2016. Prof Heymann, who chairs the committee that made the declaration, aided this decision. “It became very clear, in a very short time during the emergency committee meeting that this was an emergency,” he said. “Initially, the PHEIC was not Zika but was the clustering of microcephaly and neurological disorders.”

The severity of symptoms among adults infected is minimal, such as fever, rash and joint pain, but this disability among babies is significant.

“It’s becoming increasingly clear that microcephaly is the tip of the iceberg,” said Prof Whitworth.

The main transmission control efforts have revolved around mosquito control and personal empowerment and education, as with Ebola, to ensure people protect themselves from bites. Anyone travelling internationally has also been advised to avoid affected regions if they are at risk, such as if pregnant or wanting to get pregnant soon.

Multiple questions remain unanswered, however, to both control the epidemic and enable countries to manage the health of children born with disabilities.

Leading this research at the School is Professor Laura Rodrigues, Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology. A Brazilian herself, Prof Rodrigues knows the scientific leaders in Brazil, with whom she is cooperating, as well as the population she is working in and has witnessed the impact of the outbreak on local communities.

“There’s good understanding, but there is fear,” said Prof Rodrigues. As with many diseases, there is stigma now facing mothers whose babies have been affected. Stigma also faces pregnant women in general who live in high-risk areas, such as the state of Pernambuco, in Northeastern Brazil. Prof Rodrigues has seen the usual protective nature that people feel toward women during pregnancy be replaced “with compassion, due to the realisation that the woman is at risk,” she said.

In collaboration with Brazilian partners, Prof Rodrigues has been working with a cohort of 4,000 pregnant women across Pernambuco who were notified as having a rash during pregnancy since January 2016. She estimates that 400 to 700 of them are likely to be have been infected with the Zika virus. In terms of insight, her goals are four-fold: to measure the risk of microcephaly and other manifestations, to find out at which stages of pregnancy infection with Zika puts women at most risk, and how the babies affected will develop as they grow up. “We also want to see what are the other manifestations, like visual and hearing loss. ” she said.

Prof Rodrigues agrees that microcephaly is likely to be just the start of many symptoms affecting babies born to mothers infected with Zika. The studies in which she is involved have already found an increase in epilepsy and irritability among babies as well as visual and auditory disorders and an increase in stillbirths.

More detailed results will only emerge once the babies are born among her study group. In the meantime, Prof Rodrigues has noticed some striking solutions that have been implemented by local mothers themselves. “The mothers are organising themselves and arranging WhatsApp groups and associations,” she says. These create support groups so mothers, likely stigmatised by others in their community, feel supported, share knowledge and are able to communicate any concerns to policy makers in an instant. “They’ve been outstanding,” she says.

Such community-driven responses to the epidemic are all anyone can do for the moment while those most affected await tests, treatment and hopefully a vaccine. For Prof Heymann, this local camaraderie and strength is more crucial than awaiting biomedical solutions.

“In my own opinion, it’s about understanding,” he says. “We can’t wait for the vaccine, we have to now help people understand the issues and be able to prevent their own infection.” This is true of any outbreak, not just Zika.

The future is likely to bring more outbreaks; of this the experts are sure. But they can be prevented from becoming a PHEIC by effective control within countries themselves. “We need to help countries strengthen their health systems to deal with these infections, in order to prevent sickness and death and stop them spreading internationally,” says Prof Heymann.

“The school is especially strong in helping countries develop capacity,” he says. “We can do all we want globally, but the fact remains that if countries are able to stop infectious diseases more rapidly, everyone benefits.”

After Ebola, the region of West Africa, although not perfect, is more ready than ever. After decades of turmoil, Dr Moses believes the shock of the epidemic has resulted in positive change within his home country of Liberia.

“For the first time, government support is at its best,” he says. “Health and community support to work with health authorities is at its best.”

When the next virus inevitably arrives, the barriers will be firmly in place to stop it. Or, at least, more than before.

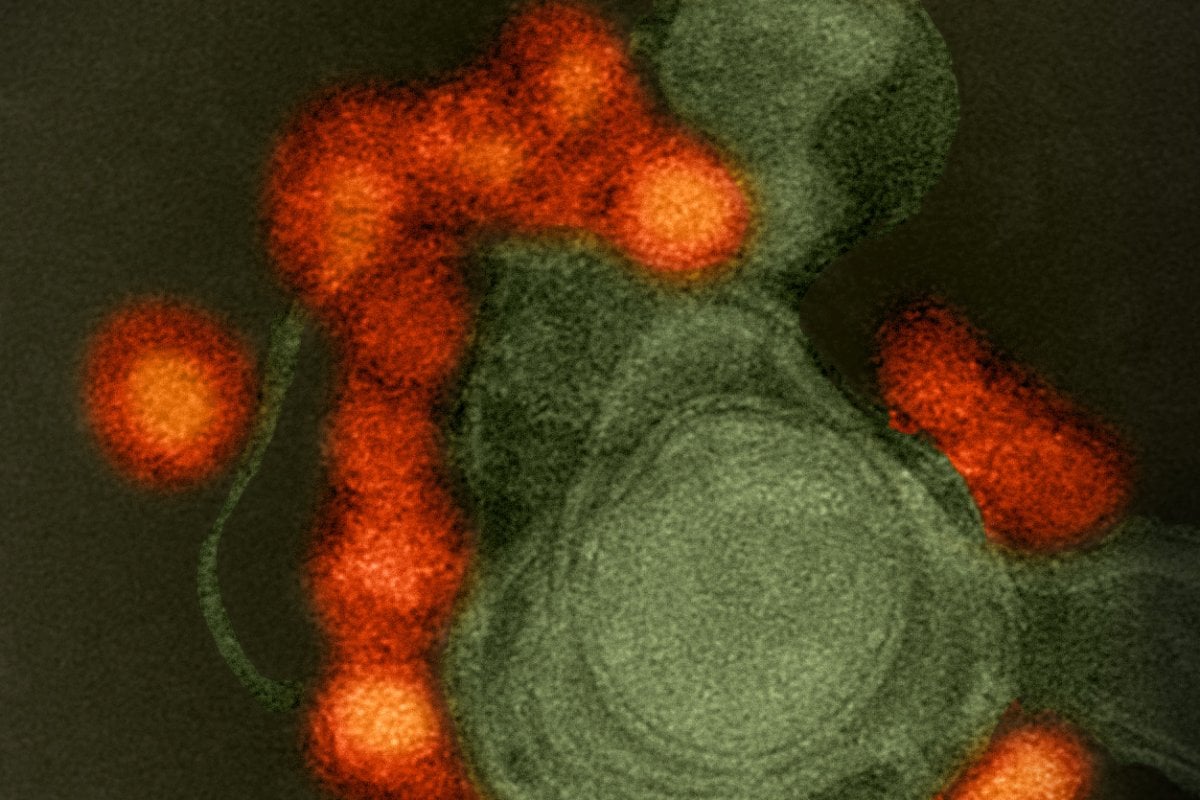

Title and cover image: Ebola signs and symptoms – Credit:Tom Mooney, LSHTM.