“Let us not equivocate: a tragedy of unprecedented proportions is unfolding in Africa,” said Nelson Mandela as he stood upon a podium before thousands. The crowd that day was not his usual audience, but he had an important message to convey.

“[It] is claiming more lives than the sum total of all wars, famines and floods, and the ravages of such deadly diseases as malaria,” he said to the room full of scientists, physicians, activists, politicians, policymakers and others who had one common interest: to put an end to this crisis.

The year was 2000 and as Mandela stood on his platform in Durban, South Africa, HIV was transmitting across local, national, and global communities, and had been doing do for almost twenty years as a global epidemic.

The scene played out at the closing address of the 13th International AIDS conference, which is today recognised as a turning point for the epidemic. It was a pivotal moment in global health where the divide between the West and lower-resource settings was evident, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and highlighted the availability — or lack of availability — of antiretroviral drugs (ARVs).

At the time, HIV continued to be transmitted in all regions of the world, infecting 3.1 million people globally that year, spreading faster in Africa. Infections were rampaging across the Eastern and Southern regions of the continent and infected 2.3 million people, and killed 1.2 million that year alone. Death could be prevented in some parts of the world, thanks to the arrival of antiretroviral drugs — but they were yet to reach Africa.

Crowds at the conference were divided on how to proceed.

“This is not an academic conference. This is, as I understand it, a gathering of human beings concerned about turning around one of the greatest threats humankind has faced, and certainly the greatest after the end of the great wars of the previous century,” Mandela had said.

And turn it around they did.

Many in the room had been pushing for what the late president was asking for and together they travelled a long, bumpy road that continues to be journeyed today — the road to end HIV.

Making change with poor resources

In 2000, truly tackling HIV rates required a radical shift in thinking.

“We knew that antiretroviral therapy was a very effective treatment,” says Prof Richard Hayes, Professor of Epidemiology and International Health at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, who attended the conference.

“But I remember at the time there was a lot of skepticism among people working in the field who said this couldn’t be delivered in these resource-poor settings,” he said.

In 1996, antiretroviral treatment (ART) had been proven an effective therapy against the progression of HIV infection to AIDS. For the first time since the epidemic began, cases of AIDS were declining in countries like the United States and the infection became manageable, rather than fatal. But in 2000, the drugs were yet to reach regions including sub-Saharan Africa.

“Many people were saying this would be a disaster and we shouldn’t even try to roll this out,” says Prof Hayes, who has been working in the field of HIV since it first emerged in the 1980s. Concerns were fuelled, he said, around the belief that widespread distribution of ARVs would not be safe, there would be poor adherence to the drugs, drug stockouts could mean people could not get their therapy, and there was concern over widescale drug resistance, which could make the drugs ineffective.

“But the 2000 AIDS conference in Durban was really the time when this was very effectively challenged… and I think people began to see this was a tool we could not afford not to use,” he says.

Unlike other regions of the world, HIV in sub-Saharan Africa was, and remains, a more generalised epidemic, meaning it affects the general population. Other regions of the world see the infection concentrate in more vulnerable, and marginalized, groups such as sex workers, injecting drug users or men who have sex with men. For example, the highest rates of HIV seen in previous Soviet states today are among injecting drug users.

Targeting a generalised epidemic meant the numbers to reach was much higher and more widespread. But that wouldn’t stop them now.

The rise of therapy…and more promising control

The next fifteen years saw a dramatic change in the global AIDS response, with ART being made more available to those who needed it most, and a new field of research that identified ways to prevent people becoming infected.

Numbers of people accessing antiretroviral treatment increased from 0.1 million in 2002 to more than 10 million people in 2014. This victory still represents only 41% of people in need of treatment, but the benefits have been huge.

“We’ve been able to show the huge impact antiretrovirals have had on mortality in the general population,” says Prof Basia Zaba, Professor of Medical Demography at the School. Prof Zaba heads the ALPHA network, which stands for Analysing Longitudinal Population-based HIV/AIDS data on Africa. The network brings together 10 population-based HIV surveillance sites located in Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Through household surveys conducted several times a year, the network obtains personal information including birth and death rates, rates at which people join and leave households, marital status, and also their HIV status. This may seem like standard information, but most countries in sub-Saharan Africa do not have vital registration, according to Prof Zaba, making routine information about the populations only available in these special demographic surveillance sites.

“We now have a picture of what HIV looks like in an ordinary community, in the whole community, not limited to those who are receiving treatment” says Prof Zaba, whose research team then measure HIV incidence and mortality based on this demographic data, helping to provide evidence on the impact of the infection within these countries.

In 2011, a landmark study in the field — known as HPTN052 — showed that in couples where one partner is HIV positive, transmission of HIV can be reduced by 96% if the person has early access to ART. Enabling greater access to ART, in Africa and globally, therefore comes with the hope that there will be fewer new infections. “This is our main area of research at the moment [as] nobody has shown this effect in an ordinary community,” says Prof Zaba.

Using treatment as prevention

Prof Hayes and his team are now directly testing the benefits that come with increased access to ART in the largest population study ever conducted in the field of HIV.

Their Population Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy, or PopART, trial began in 2013 and involves 21 communities with a total population of 1 million located in South Africa and Zambia.

Their interventions are testing the effect of HIV testing and the resulting use of ART on improving health, but also reducing numbers of new HIV infections. The intervention is intended to have a double impact – to save lives and stop transmission.

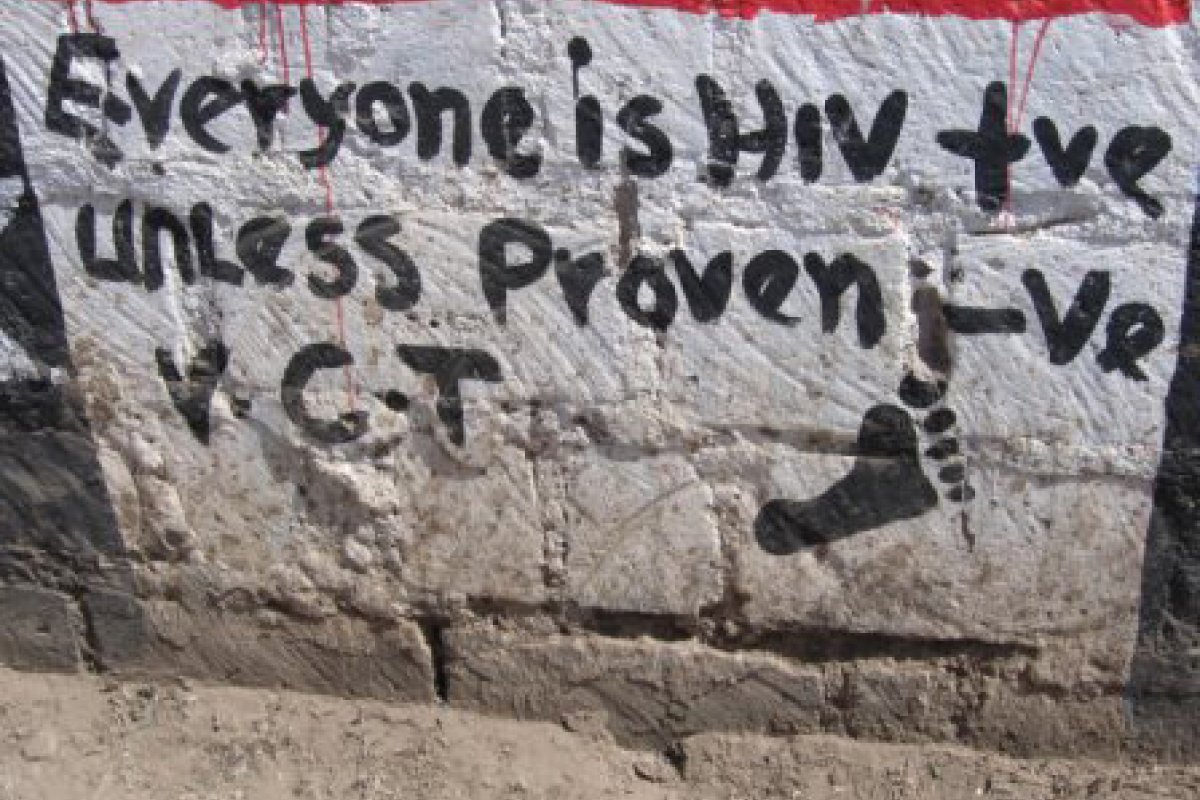

The 21 trial communities were randomly divided into intervention and control groups, the latter receive the normal standard of care, while community health workers visit the former at their homes. The health workers encourage people to be tested for HIV and, for those found to be positive, help link them to care services for immediate treatment. Additional information on services and behaviours to help prevent infection is provided, such as links to medical male circumcision, which was found to reduce new HIV infection in men by as much as 60% in research studies.

The intervention as a whole equates to combination prevention, where many aspects of HIV prevention are brought together in addition to ART.

“This is what we think is needed above all else for these highly generalised, high prevalence epidemics, particularly in Southern Africa,” says Prof Hayes. The results from the study could be pivotal in providing evidence on whether today’s ambitious goals for the epidemic, set by UNAIDS, are achievable.

Reaching new goals

Two key goals remain for all working on the HIV epidemic today: Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030, and the triple use of the number 90 for the 90:90:90 target, both set by UNAIDS. The latter goal hopes that by 2020, 90% of people with HIV will know their status, 90% of people who know their status will be accessing ART and 90% of people with the infection will have undetectable viral loads — a marker for both good health and the reduced likelihood of transmission.

The PopART trial is now more than halfway through and preliminary results from data after one year are promising. At the end of year one, 80 to 90% of people with HIV in the trial communities knew their HIV status. “That’s approaching the target set by UNAIDS,” says Prof Hayes.

At the time of the annual round visits for PopART, about 50% of those who were HIV positive were on ART. By the end of the first round that had increased to 70%, thanks to community health workers pushing harder to link people to care services.

“One of our key findings in the first year was that it was taking too long for people to link into care and actually start their ART,” says Prof Hayes.

It’s too early to identify any impact in terms of the third ‘90’ to reduce viral loads, but the next set of results will reveal more and help decide if treatment can reduce numbers of new infections.

Prof Hayes said reaching men within these communities and getting them circumcised has been a challenge. In Southern African settings, men often work away from home. In addition, circumcision is often not practiced culturally in many communities, such as in Zambia.

The approach of PopART is resource-heavy and large-scale. While governments currently have no plans to take on this kind of intense health program, Prof Hayes believes they are waiting for the evidence — such as that from his trial — before acting, particularly with regard to its cost-effectiveness.

“[If this works] there’ll be a very strong rationale for implementing this very widely in Africa,” says Prof Hayes.

“In Southern Africa we had a perfect storm where every single risk factor for HIV transmission came together”

Professor Peter Piot, Director of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

Africa is not a country

When looking at the global HIV epidemic, rates of prevalence and incidence (new infections) are significant in many regions of the world, but highest in Africa, aided by this generalized status of the epidemic.

Of the 36.9 million people living with HIV in 2014, 25.8 million of them were in Africa, 70% of the global total. This region is also where 66% of new infections occurred the same year.

However, it’s only certain countries within Africa that continue to have exceptionally high rates of infection, particularly Southern Africa.

“Sub-Saharan Africa is a very diverse continent, there are countries with HIV infections lower than London…we should not generalise,” says Prof Peter Piot, Director of the School and Professor of Global Health.

According to Prof Piot, who was also the founding Executive Director of UNAIDS, the highest burden — or hyperendemic — countries are in Southern Africa, namely South Africa, Zimbabwe, Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique. Although lower, rates are also high in East Africa.

“This diversity is rooted in several things,” says Prof Piot. These include any history of apartheid and colonial times where men, women and families were separated and families broken up. Many countries also have employment in industries such as mining, which leads to a concentration of segregated males working as labourers.

If you then add in cultural factors such as circumcision not being the norm and a greater proportion of conflict-affected settings, the strength of the epidemic is easy to understand. Once the prevalence of a disease is high, the chances of contracting it are then also high.

“In Southern Africa we had a perfect storm where every single risk factor for HIV transmission came together,” says Prof Piot. “Then for years there was no treatment, so we wasted a lot of precious time.”

The most vulnerable group in this region, and also globally, are women and girls as they are often based in communities where they face gender violence, inequality and poverty.

“Gender inequality is a central issue that shapes women’s vulnerability to HIV,” says Prof Charlotte Watts, founder of the Gender Violence and Health Centre at the School, who is currently seconded to the Department for International Development (DFID) as their Chief Scientific Adviser. “Power imbalances between women and men, both social and economic, can severely limit women’s options to protect themselves from HIV.”

According to Prof Watts, “Social constructions of masculinity, that assert that men should be dominant, and assign status to having multiple sexual partners, and constructions of femininity, that assign women to being submissive, and put limit a woman’s ability to negotiate safer sex with a partner.” Women can struggle to negotiate for safer sex, even when they suspect their partner may be infected. Economic inequalities between women and men also lead to a reliance on men for both income and the ability to look after any children, further compounding their situation.

Globally, women constitute more than half of the numbers infected with HIV, and in sub-Saharan Africa, women make up 58% of all people living with the infection, according to UNAIDS.

Women are also at least twice more likely to acquire HIV from men during sexual intercourse and violence against women is emerging as an important risk factor. “What we see from epidemiological evidence in sub-Saharan Africa is that women who are in violent relationships are at greater risk of HIV than women who are in more equitable relationships,” says Prof Watts, who focuses on gender equality and reducing women’s risk of infection. “The reasons are multiple, being related not only to the potential risk from forced sex, but also from a greater risk that a violent partner has other risk behaviours, that increase his risk of HIV,” she says.

Recent evidence has highlighted the greater risk facing adolescent girls. In 2014, almost 62% of new HIV infections among adolescents as a whole, occurred among adolescent girls, according to UNAIDS. Among this age group, transactional sex is likely to play an important role in some settings.

“A woman might exchange sex for access to finances, a job or to acquire essential items such as sanitary wear or school fees, through to commodities such as air credit on their phone,” says Prof Watts. Relationships with older men are also not uncommon. “If these relationships are with men who are at higher risk of HIV, this puts adolescent girls at increased HIV risk,” she says.

Prof Watt’s group are currently trialling a range of interventions, including community studies that aim to empower women to increase their economic and social independence, and also be better able to communicate openly and peacefully to solve any problems in their relationships. A recent trial in Uganda worked with whole communities, including women and men, the police, religious and local leaders, to get them discussing and thinking about the implications of gender inequality and violence, and to support them to try new, more equitable and less violent behaviours.

“Women’s experience of physical partner violence in those communities reduced by over a half,” says Prof Watts. “”Men in intervention communities also reported less extramarital sexual relationships.” Through their research, her team is showing that beliefs and practices that are seemingly set within a community can be changed.

“It’s easy to think that issues are too ingrained, too difficult, too complex, but what our research is showing is that we can achieve quite a big impact over programmatic timeframes,” she says.

To target adolescents, the team is also using sport to engage the adolescents and get both boys and girls talking about sex, equality and relationships. The hope is that by reaching them early and changing attitudes, this next generation will have new behaviours to pass on to future generations. “Our interventions do suggest that things change,” says Prof Watts.

Working to change societal and cultural factors can seem too challenging for some in the field, who instead turn to more technological or biological solutions to fight HIV, but as the disease involves sex and relationships, such a distinction is impossible.

“HIV is not simple, it’s about people, about sex, about inequalities and about massive societal efforts across the world,” says Prof Piot.

“It took about 10 years since the discovery of treatment for ARV until 1 million Africans had access to that therapy, that illustrated that it’s not enough to have a technological breakthrough…you need the money, price reduction and people need to be open to the realities of HIV infections and you need to build up the systems,” he says.

The key to prevention?

In addition to PopART, many trials and technologies are currently underway to help prevent infection with HIV. One of which is the rise of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP).

PrEP is the use of ARVs by people who are uninfected to protect themselves from contracting HIV, particularly women who could hopefully be discreet when using it. The approach is an infant in the field of HIV control, but greater attention is being given to its potential impact.

Two large trials by others in the field recently showed some promise in the use of a vaginal ring that slowly releases ARVs into a woman’s vagina. The result showed a 30% efficacy against infection. The study included more than 4,500 women in South Africa, Malawi, Uganda, and Zimbabwe.

Although 30% may not seem like much, a little protection is better than none, especially for women who have limited options to protect themselves. “Part of the reason for the 30% result was a lack of consistency in diaphragm use,” says Prof Watts. “There’s more research to be done to identify how to increase the consistency of use in the future. Similar challenges were faced in the early years of contraceptive development, which were eventually overcome.”

Other options for PrEP involve use of ARV drugs by HIV negative individuals at high risk of infection. It’s widely debated, as studies have shown to provide high levels of protection, but pills must be taken consistently.

Another growing area is the use of microbicides by women to protect them from infection specifically during sexual intercourse. “What we’ve learned from family planning is the more options we have, the higher the coverage. The effective introduction of PrEP and the development of additional technologies that work for women and adolescents are important piece that we need to tackle,” says Prof Watts.

After years looking for a single solution to HIV, the growing consensus is that to truly combat the virus, there will need to be a combination of approaches.

“We need to combine new advances in technologies with other components that support women’s empowerment and greater equality in relationships,” says Prof Watts. “The effective introduction of PrEP and the development of additional technologies that work for women and adolescents are important piece that we need to tackle.”

It’s a long road ahead still. “There is a lot of uncertainty at the moment as to how PrEP should be implemented, who should be offered it and for how long and through what kinds of mechanisms, how should the services be provided,” says Prof Hayes.

A return to Durban

The challenges raised will be key areas of focus this summer when the International AIDS conference returns to Durban, South Africa, in July.

Sixteen years after an inspirational speech, a reality check and strong activism kick started a force for HIV to be reckoned with, and the world now has fewer infections each year and more people on treatment. Fewer numbers are dying from the disease, but it’s by no means over yet.

Durban, and the state of Kwazulu-Natal it’s located in, harbour among the highest rates of HIV in the world, most notably among its rural communities. “In Kwazulu-Natal, between 3 and 9% of young women become infected with HIV every year, which means that by the time they’re 35, about 30-40% are infected, which is absolutely beyond belief,” says Prof Piot.

The epidemic is at another pivotal turning point — this time calling for greater prevention.

“The last 15 years we had serious progress and now we need to consolidate that progress,” says Prof Piot, highlighting the rates in the region to show people they cannot become complacent by now seeing the disease as ‘manageable’. He believes the field needs to be re-energized to truly end the virus — not just deaths from AIDS — and that more attention must be given to HIV prevention after years of focus on treatment.

“We must invest far more in HIV prevention as efforts are now mostly on antiretroviral therapy and we will not treat ourselves out of this epidemic,” says Prof Piot.

As millions continue to get infected each year, the total number of people living with the disease — currently 35.9 million globally — will rise.

“[It’s] very clear that if we lose sight of the goal and fail to make the investments needed to sustain both prevention and treatment, we will start going backwards,” says Prof Hayes.

“That’s why I think this is still really an emergency.”

Title and cover image:© CDC Global – World AIDS Day Namibia, Luderitz Children having fun.