“If things go on like this, in the coming years we may have a season without any rain,” says 45-year old Chikumbutso Patson Kayira , a Malawian farmer based in the country’s northern capital of Mzuzu.

Mr Kayira farms mostly maize, his country’s staple, across 12 hectares of land he inherited from his parents. His family of five now relies on the crop for sustenance, as they consume porridge and a thick, mashed maize dish known locally as ‘nsima’ as their staple meals each day.

The majority of Malawians rely on this grain to survive, but Mr Kayira is now concerned about his family’s future.

“We will have nothing to eat,” he says. Within just five years, changes in rainfall and weather patterns have halved his yield.

Until recently, Mr Kayira’s land had been fruitful, yielding enough crops, such as maize, but also groundnut and even tobacco, to feed his family, while leaving enough as extra for sale at the market. He has worked the same piece of land for 12 years, and used to harvest more than 50 bags of maize, each weighing 50 kilograms, each season.

“Now, if I can have 25 bags, I’ve done it,” he says, disheartened by this big decline.

“The climate has changed,” he says, to describe the reasons underlying this change to his land and life.

Changing climate, changing food

Malawi is located in sub-Saharan Africa, a region of the world where two seasons dominate; the dry and rainy season. The rains that once came for months at a time were essential for agricultural success across the whole region. But these rains only come a few months each year in Malawi, according to Mr Kayira.

“For the last few seasons we experienced rains maybe for two months only,” he said. “Most of the time we have dry spells.”

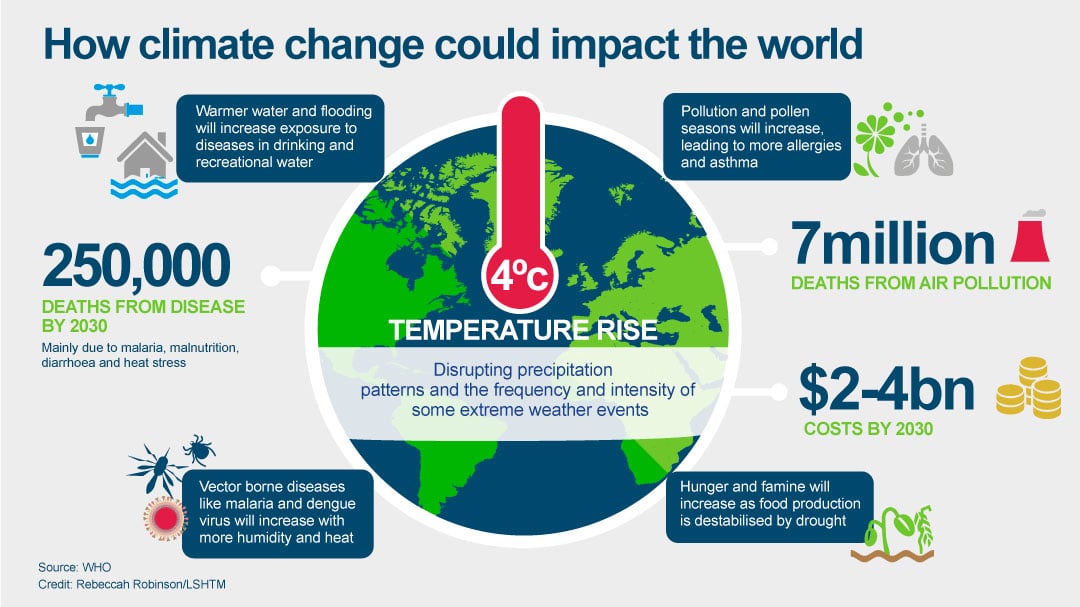

When many of us think about climate change, our minds naturally wander to gas emissions, increasing temperatures and melting ice caps that are causing sea levels to rise. But the consequences stemming from this run deep.

“Environmental change can affect human health in many ways,” says Sir Andy Haines, Professor of Public Health and Primary Care at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. He highlights factors such as changes in temperature and freshwater availability as “having major implications for future food production.”

In many ways, these implications have already set in.

“Up until now, very few people have been looking at the combination of factors,” says Prof Haines. Increasing heat and changing rainfall patterns will lead to a decrease in crops, then a decrease in nutrition, and an increase in stunting among children, particularly in the developing regions of the world.

These are the fears of Mr Kayira.

If things continue to progress at their current speed, the world is expected to increase in temperature by more than four degrees by the end of this century, which in already hot regions of the world, will prove disastrous.

“The intention is to stay below two degrees,” says Prof Haines. “Otherwise there could be a catastrophic effect.” One degree has already been added to the global temperature since industrial times, leaving just one more degree to spare. Even then, the true goal is to add just half a degree, instead of a whole one, to ensure a rise of just 1.5 degrees.

Why this limit? This was the goal determined during the 2015 climate conference in Paris, COP21, where 195 countries adopted a global action plan to mitigate climate change in a legally binding agreement. One part of the plan was to limit the temperature increase, but as well as goals, Prof Haines wants to see action.

“Measures are currently not in place to achieve this goal,” he said, so researchers at the School are exploring the health implications of different policies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as well as the health effects of climate change. A key priority comes back to the food needed on everyone’s plate — both getting it there as well what we decide to put on it.

“Providing food for the growing population in the face of these environmental changes will be one of the great challenges of our century,” admits Prof Haines.

Healthier food, healthier planet

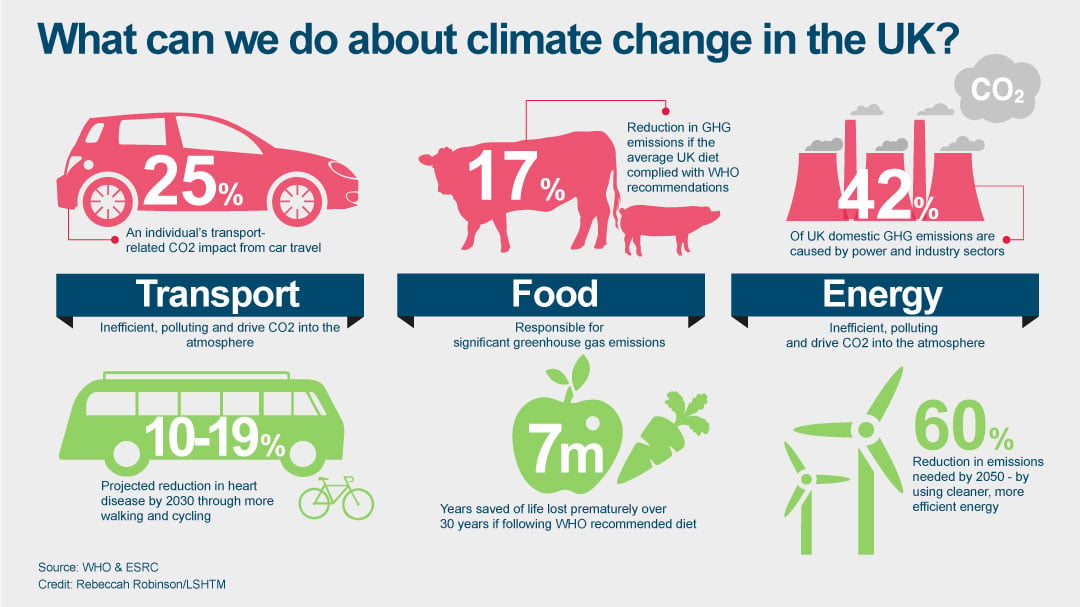

Diets may vary significantly across countries and communities globally, but it is now fairly well-accepted that the typical Western diet is among the worst. It’s not only bad for an individual’s health, but also the environment.

Western diets are typically rich in meat, sugars, starch, and saturated fats, while remaining low in fibre, vegetables and wholegrain. The consequences on health include a greater risk of obesity, diabetes and other lifestyle diseases but, from an environmental perspective, the associated greenhouse gas emissions from producing these foods in high quantity are significant.

“The environment can impact the ability of the food system to produce healthier nutritious diets, but the diets that we eat can equally impact the environment,” says Dr Alan Dangour, Reader in Food and Nutrition for Global Health at the School.

“We need to realise that the production of food can have a major impact on the environment due to it being a major contributor to environmental stress, both through greenhouse gas emission and water use,” he says.

To highlight this he compares quantities of water and carbon dioxide consumed to make various food products. One 200g steak, for example, uses the same amount of water as someone taking 23 showers and produces carbon dioxide equating to driving a distance of 32km. In contrast, one portion of fruit, such as an apple, uses the equivalent of one four-minute shower, and driving just 0.6km. In fairness, they are very different meals, and quantities of food, but the point is clear. If people eat more fruits and vegetables and less meat, they’ll be healthier and so will their planet.

The Western diet is not the only one to blame though. Typical Asian diets, rich in rice grains, also make their mark as paddy fields also produce potent amounts of methane. The warm, waterlogged fields provide the perfect environment for methane-producing microorganisms to flourish and decompose organic materials, resulting in the fields accounting for up to 20% of methane produced by humans.

“But we need to eat,” points out Dr Dangour whose team at the School is now researching how diets could be subtly improved to meet the goals set by the Paris agreement.

“What we need to think about is which bits of agricultural production are the costliest on the environment,” he says. The top culprit? Meat– and dairy.

According to a report by the Food and Agriculture Organization, published this month, livestock are responsible for 20% of global greenhouse gas emissions, which is greater than that caused by the transport sector. It is also estimated that 40% of the world’s grains are used to feed livestock — not humans. As demands for meat and dairy rise, so will these greenhouse gases. The Chatham House report states that the goal to keep temperature rise below two degrees will not be met if no changes are made to levels of meat and dairy consumption worldwide.

“The largest cost is the production of animal-sourced foods,” says Dr Dangour. While the world’s population has doubled in the last 50 years, it’s appetite for meat has quadrupled, according to Prof Haines, but in his efforts, Dr Dangour acknowledges it is impractical to suggest the world become vegetarians, or even pescatarians, as fisheries are another industry stretched to their maximum due to global demands.

“A little bit of animal-sourced food is quite important for diets, especially for children,” says Dr Dangour. “So it’s the balance and the trade-offs. What are the trade-offs between the production of the foods we want to eat and the environmental cost to the planet?”

This balance is exactly what his team has been exploring, through two very different diets – the British and Indian diet.

“The UK diet contains insufficient amounts of fruit and vegetables, too much sugar and salt and too much meat really,” says Dr Dangour. “Those are the primary changes that are needed.”

If these common meal components were replaced with larger quantities of vegetables while the frequency, and quantity, of meat is reduced, the impact is surprisingly significant, as Dr Dangour’s research has shown.

In one study, his team modeled a range of outcomes based on different levels of ‘optimisation’ applied to the average UK diet. WHO recommendations are extensive, but include suggestions of eating less than five grams of salt per day and at least five portions of fruit and vegetables per day, with potatoes, cassava, sweet potato and other starchy root vegetables not classified as vegetable.

Interestingly, they found that if diets were changed to meet WHO recommendations, greenhouse gases could fall by an astonishing 17% from this change alone. As an added benefit, average life expectancy was shown to increase by eight months. “It’s a win-win,” says Dr Dangour. “If you change the balance of animal-sourced foods and increase the amounts of fruits and vegetables in the diets, then that has clear demonstrated public health benefits.”

If they pushed diets even further than recommendations, to limit meat extensively with diets consisting mostly of fruits, vegetables and grains, reductions in greenhouse gas emissions could reach up to 40%. But Dr Dangour accepts this would be too much to ask of people and would result in minimal impact due to there being less uptake than more realistic options, like the one above.

“The diet was still relatively similar to what we’re now eating, it would just be healthier and environmentally better,” he says. The goal now is to spread the word and make people aware of the co-benefits of changing their diets, even if just marginally, for the better.

Similar benefits on both sides of the food fence can also be achieved across the globe, not just in the UK. Dr Dangour’s team recently explored the situation in modern-day India, a country where diets have changed remarkably in a matter of years.

By analysing data sets from 7,000 people across multiple spots in India, in both urban and rural settings, his team saw “quite distinct dietary patterns within the data.” While on one hand there are very traditional, largely vegetarian diets, consisting of high amounts of rice accompanied by small portions of vegetables, on the other hand there are mildly traditional diets with the addition of a lot of animal-sourced foods, sugar and cakes.

Dr Dangour noted that while the traditional diet tended to be among rural and poorer people, the urban diet was among younger people, who are slightly more affluent. “This is called the nutrition transition,” he said, describing how as people move away from their rural homes and into the city, their diet does not move with them and instead becomes one with more fast food and irregular hours of eating.

The consequences are two-fold, affecting a human’s health and their environment.

“The urban diet has a much higher calorie intake in general and is much more likely to predispose you to noncommunicable diseases, such as diabetes and obesity,” said Dr Dangour. But negative environmental impacts are less clear cut, as the rice within the traditional diet produces greenhouse gas emissions, so it’s not just down to the meat.

“What we’re trying to understand in India, for the very first time, is understand the greenhouse gas and water emissions associated with current diets in India,” said Dr Dangour who wants to use his data to help devise policy options for the Indian government as their population grows beyond 1.2 billion people. “If the whole of India transitions to the urban diet, that’s going to be significant for population health, but it’s also going to have a major impact on the environment.”

When it comes to food, however, as well as the impact of people’s diet affecting the environment, the subsequent changes in environment will then change the global production, and trade, of our foods.

“For me the key thing is a focus on both nutrition and food security,” said Dr Dangour, who hopes this will be a top priority as global leaders from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change meet in Morocco next month for COP22.

Prof Haines. “There will be serious effects of multiple environmental changes on future food production,” he says, pointing out changes beyond meat and vegetables including seafood, through ocean acidification and fisheries reaching their capacity. “Much aquaculture itself is unsustainable, though people are trying now to make it sustainable, and ecologists don’t really know the full impact ocean acidification will have.”

Global markets will also change.

As tropical countries increase in temperature, their agricultural production will suffer, as Mr Kayira’s experience shows. “It is estimated and modeled, that there will be major changes in the abilities of farmers in different parts of the world to produce foods,” says Dr Dangour. This will ultimately have an impact on the availability and price of foods, and the ability of people to buy healthy, nutritious diets.

“This reduction in the ability to produce foods is going to have major impacts on food security and could lead to hunger and starvation in some countries,” he says.

“Providing food for the growing population in the face of these environmental changes will be one of the great challenges of our century,”

Sir Andy Haines, Professor of Public Health and Primary Care at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

However, the cooler regions of the world will face the opposite. They will suddenly see their land become hospitable, and more productive, enabling them to produce new crops. “So it might be that the losses in some parts of the word are made up by the gains in other parts of the world.”

But economic inequality could then become even wider between these two regions of the world, with poorer countries suffering as they rely heavily on agriculture as a source of national income, which could lead to protests, warns Dr Dangour.

The public outcry in response to a food shortage was seen in 2008, when there was a spike in the price of foods globally, resulting in riots in 20 countries around the world.

“People need to eat, and if there’s no food, people will take to the streets,” he says.

Redesigning cities

Prof Haines is focusing on the consequences of urbanization and overpopulation of the sustainable city, and what it will actually take for cities to become sustainable.

“Cities are crucial because they are responsible for the majority of the world’s economic activity,” said Prof Haines, adding that cities account for over 70% of greenhouse gas emissions, while housing over 50% of the world’s population and exceeding 85% in some countries.

And this will only get worse.

“We’re building more cities,” says Dr Sari Kovats, a senior lecturer and Director of the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Environmental Change and Health at the School, who also researches this issue. “In Africa and Asia, there’s been a huge social change of people moving to cities and more cities are going to be built, which we know will have implications for human health and the global environment”

The issue is in the West as well.

“The UK population is still growing, there will need to be a million more people accommodated in London. What implications will that have for health, in terms of city design? Are cities going to spread out leading to a loss of rural green space?” asks Dr Kovats.

There is a lot of interest at the moment about how cities should be designed, for example, whether they should be dense and high-rise as this would facilitate active travel with people walking to work.

And then there are the homes themselves with a city.

“We still have a lot of uninsulated houses,” she says. “Most of the world is like that. The world was not designed to be highly-efficient,” she says.

The issue of insulation highlights one current consequence of climate change, as our homes are ill-prepared to deal with it. Ironically, while insulation was put in place to reduce energy wastage and ensure efficiency, it’s now causing problems as the world increasingly heats up. Some houses have been made too energy efficient, and as a result, they’re becoming too hot.

“There’s been a lot of focus around making houses more energy efficient, but if you make the house too energy efficient and seal it up, you’ve reduced ventilation, then that can have unintended consequences,” says Dr Kovats. “Research by HPRU colleagues at UCL has shown about 20% of current dwelling are at risk of overheating even in average summer, that’s quite high, and will only increase as temperatures increase.”

Another way overheating is a problem is due to the increasing prevalence of heat waves in regions of the world not used to handling them — like the UK. In August 2003, Europe experienced a major heat wave, where an estimated 35,000 people died prematurely, including 2,000 in the UK, from overheating that exacerbated existing health conditions or the impacts of old age.

Temperatures reached as much as 38.5 degrees Celsius in the UK – the highest ever recorded.

“It’s been shown that heat waves cause a short term increase in mortality, so these are premature deaths,” says Dr Kovats.

In the UK, the heat caused some roads to melt and rail networks to fail, resulting in a joint project between the Met Office and Department of Health called the Heat-Health Watch, which now gives advanced warning if the UK is expected to have a heatwave. The UK’s rail company, Network Rail, also now imposes speed restrictions for trains when the temperature goes above 30 degrees Celsius.

“More than 10 years on, there’s been a few more heat waves and a lot of interest in developing the plan to prevent people getting sick or dying during a heat wave,” says Dr Kovats.

Both Prof Haines and Dr Kovats worked on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report, which looked at health risks if climate change continues as projected until mid-century and beyond. In this, they highlighted the issues we’ll increasingly face if the world’s average temperature increases above the preferred limit of two degrees.

“Globally, there has been an increase in very hot days, which is what you would expect with an increase in average temperatures,” said Dr Kovats.

The consequences extend beyond overheating in homes – to outdoor injuries and the inability of people to work outside, which in turn will further impact the economy.

“There’s a lot of interest now in very hot temperatures, extreme temperatures, and what this might mean to daily activities and for people who have to work outside,” says Dr Kovats. “If you’re outside in the heat for too long and get heat stroke you’ve got quite a high risk of dying. It’s a very severe health issue.”

But despite this severity, Dr Kovats admits the HPRU in Environmental Change and Health are addressing another weather event of somewhat more serious concern: flooding.

“Flooding is even more complex,” she says, as dealing with them becomes about flood defences and making decisions about what and where should be protected, meaning experts are required to value people and properties. “It’s very difficult, because the water has to go somewhere.”

Though flood risks have increased, Dr Kovats is unsure whether flooding itself has become more common, because people are increasingly living in flood zones. But eventually, it will rise up. “Climate change is likely to increase flood risk, certainly for coastal flooding,” she says.

Unlike physical health complications that arise from heatwaves, the health impact of flooding is more psychological, particularly for people who repeatedly endure it. “It’s a very complicated picture: There are large social costs, a loss of social support if you have to move far away, but also some benefits to social cohesion during flooding,” says Dr Kovats.

The extremity of these two weather events highlights the extreme variation in the consequences if the issue of these gases in our atmosphere is not taken seriously enough. While people in the UK have extreme heat and extreme floods to worry about, Mr Kayira, may sit in hope of some extensive water to come his way to quench the thirst of his crops.

But regardless of the location, people are going to be stranded and their security threatened, and in case commitments by global leaders are not met, farmers like Mr Kayira, are testing their own, local solutions.

“We’re involving ourselves in agroforestry and intercropping,” he says, as he is now alternating some of his maize with soya beans and ground nut to help enrich his soil. But it will take everyone on the planet making these changes to make a real difference to his land.

The need for change is urgent.

“We depend on agriculture,” he said. “If the weather is not favourable it will create a lot of problems … and this is what’s already happening.”

Title and cover image:© Danish Red Cross/Jakob Dall