The scene is unlike any other. Thousands of people. Millions in total. All of them on the move.

The people? Forced migrants, who move across the unknown in search of solace as they flee the only place they call home. Some are wounded, others ill and many traumatised, but they will not let this stop them from seeking refuge elsewhere as they make this journey towards a safer, better life.

“They have to keep moving because as long as a border is open, it’s their only chance,” says Dr Karl Blanchet Co-founder of the Public Health and Humanitarian Crises Group at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine.

His words are the thoughts of more than 13.9 million people who were forced to flee their homes in 2014. They are the live-saving thoughts of a refugee.

All you have is your health

The majority of refugees are healthy. “You have to be quite healthy simply to make the journey to a country,” says Martin McKee, Professor of European Public Health at the School. Migrants must be strong to face the horrors encountered when crossing mountains and seas, with the ever-present risk of death from drowning, exposure, or even attacks. They need their health to embark on the journey.

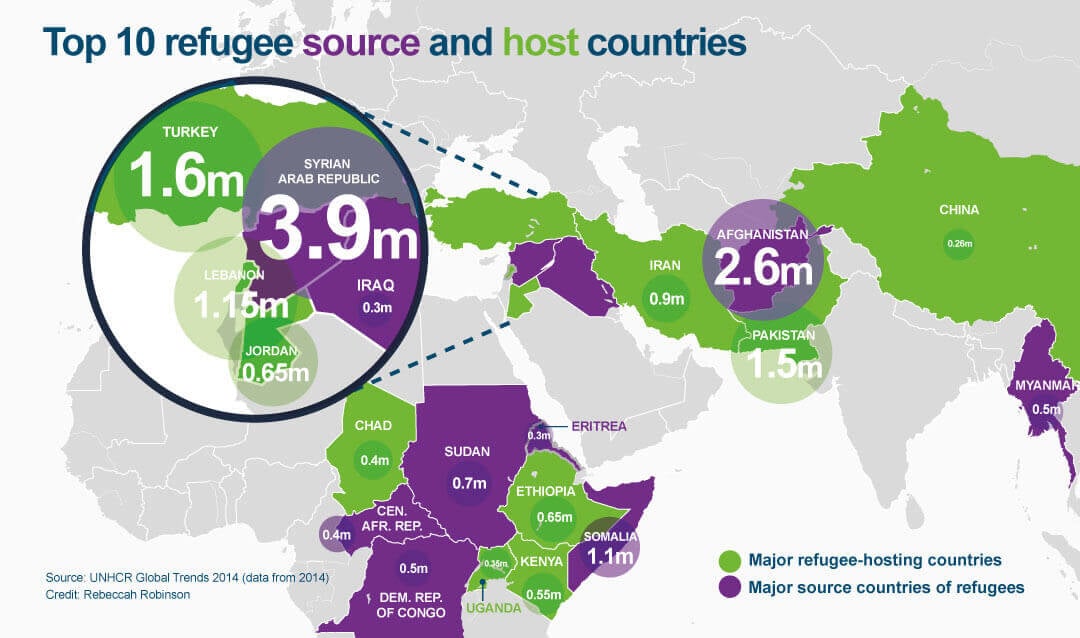

Today, one in four refugees begin their journey in Syria, the main source of refugees globally. Waves of both migrants and refugees are now traversing neighbouring continents in search of a better future and are unable to stop until they reach their destination.

For many, the destination is unknown.

“There’s no time to wait,” says Dr Karl Blanchet; who has seen, first-hand, the continuous and rapid movement of people crossing whichever border is available to them as they flee conflict and persecution. Time is of the essence for Dr Blanchet and all public health teams as they race to treat these mobile populations.

“It’s very hard to save lives while people are walking,” he says.

Where have people been? What risks have they faced? Where are they headed to next? These are key questions health teams need answered to do their job. Often these answers are elusive, in an informational transit, prolonged by the language and cultural barriers of those displaced.

Numbers may be at their highest to date, but this migration of people is nothing new.

“It’s a phenomenon that has been increasing in recent decades,” says Dr Bayard Roberts, fellow Co-founder of the Public Health and Humanitarian Crises Group at the School. According to Roberts, the mass movement of migrants and refugees in Europe in 2015 is emblematic of the situation globally, and a feature of globalisation. People have greater access than ever to greener, safer, pastures.

One man’s journey

Arif Sahar fled to Pakistan from his home country of Afghanistan more than 20 years ago — aged 14 years — as the Taliban began their control of his country. Prior to Syria, the main source of refugees globally was Afghanistan, which held its place at the top for three years running. In 2000, during the height of the Taliban regime’s power, Sahar chose to move further afield and build himself a better future.

His first stop was Iran.

“We stayed for six weeks gathering people and found a broker,” says Sahar looking back at the steps he took to get started. Forty-five days later, he reached Turkey — which now hosts the largest number of refugees globally, standing at 1.59 million in 2014. Here, Sahar was locked up by traffickers for more than one month and his health deteriorated.

“We were kept in a small room and everyone fell ill,” says Sahar. He recalls having no clean water, sanitation or food as he — and many others — were hidden to avoid the authorities. Sahar resorted to drugs others had brought with them to treat their own, chronic, health conditions. “They didn’t work as it took two weeks to feel any better,” he says.

Once freed and able to access healthcare in Turkey, he found that services were too expensive and he couldn’t obtain the medication he needed. All the while, the fear remained of being caught in his tracks.

"We were kept in a small room so everyone fell ill."

Arif Sahar, Afghan Refugee

Over one year, Sahar travelled through Turkey, Greece, Italy, and France to reach the United Kingdom where he now lives. He met many people like himself along the way and formed many friendships and connections, many of which he was forced to leave behind as people grew less able to carry on. “I look back now and feel sad I had to leave my friend in Greece…he grew ill and had developed a form of TB,” says Sahar. His friend had made the sacrifice not to hold the others behind and still remains in Greece today.

The majority of Sahar’s journey was on foot, leaving him with aching legs thereafter. Throughout his expedition he encountered multiple forms of healthcare ranging from private, to humanitarian aid and official United Nations (UN) camps. He reached the UK in 2001 and is now back in the UK studying for his PhD. “I want to go back and help my country,” says Sahar.

An evolving community

This route to a new life has not changed much since Sahar path in 2001, but the nature of the people moving has. The demographic profile of people now finding themselves displaced has evolved and with this comes a new health profile to be dealt with. “We need to understand the affected population,” says Dr Roberts.

When people are displaced an emergency response kicks in and the challenge begins to keep them alive and well. Typically, the response begins with crisis intervention.

“You start with life-saving services, such as preventing disease outbreaks through vaccinations,” says Dr Roberts. The close proximity people find themselves during migration and mass movement puts them at constant risk of new infections. People coming from spacious, rural villages can now find themselves surrounded by hundreds or thousands of people in a form of “moving town” and facing new risks in every location they encounter.

But this is addressed through screening, diagnosis, treatment and immunisation among those displaced.

“One would expect an essential package of services and medicines,” says Dr Roberts. Sanitation, malnutrition and maternal health services are also a priority to ensure the survival and wellbeing of these newly formed — but transient — communities.

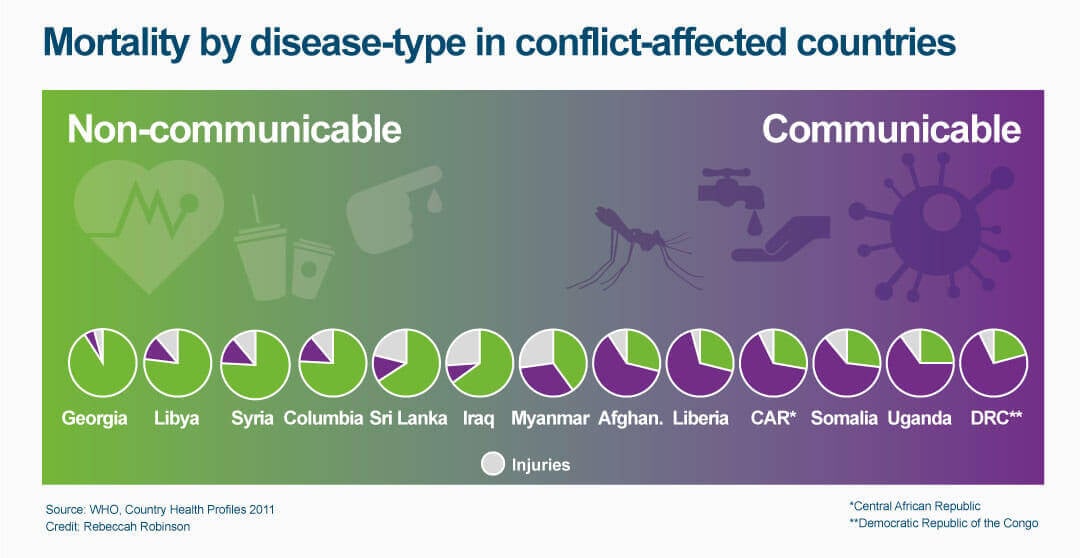

Dr Roberts believes provisions today should expand beyond communicable disease and include more chronic, non-communicable disorders. “People living with heart disease or diabetes need to maintain treatment before complications set in,” says Dr Roberts. Failing to help them could prove fatal.

The occurrence of conflict in more middle-income settings, such as Syria, involves treating a new group of conditions found among more affluent populations. In 2014, 7.4% of the Syrian population was diabetic, according to the International Diabetes Federation, and in their prior life, treatment would have been readily available, and accessible.

“With increasing migration from Syria and Iraq, people are coming from countries with reasonably well functioning health systems,” says Prof McKee.

The problem, however, is the additional complexity that comes with this change, such as treating the later stages of diabetes, cancer or cardiovascular disease. A careful selection process is required to identify those with the greatest need. “This is a huge new challenge to the humanitarian sector and it’s generally much more expensive,” says Dr Roberts .

Remembering the past

People classed as refugees are deemed so because they are forced to leave their country due to conflict, persecution or natural disasters. Their last memories will have been tormenting and emotional.

“The kind of populations we work on, such as trafficked persons and asylum seekers, are usually people who have been through traumatic events,” says Dr Cathy Zimmerman, Reader in gender violence and health at the School, who highlights how the main health issues affecting displaced people is their mental health.

There is growing recognition that the psychological stress of exposure to violence, being forced to flee your home or country, and loss of all social networks, has massive health consequences.

“[People] have often witnessed violence, experienced it themselves, or suffered various forms of deprivation or exploitation. Women and girls, in particular, are vulnerable to sexual abuse and exploitation,” Dr Zimmerman says. Her team researches mental health, including post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety.

“If you ask what the most obvious health issue is, it’s mental health,” says Dr Zimmerman.

She works mainly with people trafficked for various forms of exploitation. Her team’s research includes the health and well-being of trafficked people and the measures needed to prevent unsafe migration, and the subsequent health consequences.

“There’s a migration process,” says Dr Zimmerman who has indicated that the various stages of a migrant’s journey can adversely affect their health – pre-departure, travel and destination. However, each stage offers opportunity for practitioners to intervene to provide care. “Even once they arrive, there are all sorts of risks, including health service access and even harassment and abuse on the streets,” she says, adding it’s a big contrast to the hope of a safe haven.

“Clearly conflict is going to exacerbate poor mental health,” agrees Dr Roberts, who also researches this issue. He investigates the effect on people forced to flee within their own country, known as internal displacement. There were more than 38 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) in 2014, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

The mental health response includes ensuring safety and security to those finding themselves in new environments, and the provision of safe spaces for discussion and counselling as needed. “People need to discuss their experience,” says Dr Roberts. This needs a clear understanding of communities and cultures to adapt and suit each population.

The impact of poor mental health goes far beyond the individual.

The suffering extends to the loved ones of the person experiencing a mental disorder, and can result in loss of social functioning and productivity. “It has a long-lasting, pervasive influence on individuals and communities,” says Dr Roberts.

His team plans to begin a study in Ukraine investigating the mental health of people currently displaced within the country. The objective is to identify the burden of mental health disorders and current levels of access to services for those affected.

This follows on from recent work with IDPs in Georgia where people were found to have elevated levels of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and anxiety, onset not only by experiencing trauma, but also the daily stresses of being forced to leave your home. High levels of alcohol abuse were also seen among men. “Harmful use of alcohol is totally neglected in the humanitarian field,” says Dr Roberts.

Losing your identity

The transition from working professional to refugee changes how a person is perceived. They go from a person, to a number –- and their world changes.

“They lose their professional status as soon as they became a refugee,” says Dr Blanchet who has seen professionals metaphorically stripped of their skills and qualifications once they leave their own countries. “Their main identity is ‘Refugee’ and no longer a doctor,” he says.

The surge in movement from previously middle-income countries, like Syria, has led to teachers, doctors, nurses and other skilled professionals being among those on the move and unable to use their skills to their advantage. Dr Blanchet has witnessed this in Lebanon.

Lebanon is second only to Turkey for hosting the greatest number of refugees globally. With 1.15 million refugees living there at the end of 2014 according to UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), more than one quarter of the country’s population are refugees, a greater proportion than any other country. Despite this domination, the life of a refugee remains difficult. There are no official refugee camps in the country, people remain unable to work and have limited access to Lebanese health services, which they must pay in part for using. Dr Blanchet has been working in the Bekaa valley where he believes skills could be used to help the country’s response effort. His goal is to harness this unappreciated skillset.

In collaboration with Lebanon’s Ministry of Public Health, he plans to find a way to deliver aid informally through Syrian refugees. “They have access to local knowledge, they know the needs of the population and they know who is where,” says Dr Blanchet, who also wants to use this access to inform Lebanese health professionals. He has established a network of informants who are happy to help for free.

“Most of the time families don’t know where the right services are,” says Dr Blanchet. Now, the nurses and doctors mingling among them are making this clearer and helping with primary care and access to the country’s doctors.

“The Lebanese doctors now know exactly what to do and can save lives,” says Dr Blanchet. But he’s not done there.

Dr Blanchet wants to go one step further and use these skills while people are on the move. “Among these people you have health professionals who live exactly the same experience and walk the same walk,” says Dr Blanchet. He wants to equip them with drugs and treatments to help people suffering around them and deliver the first stages of care.

“If we can identify all the professionals in this crowd…[and] ask them to register, it could be interesting,” says Dr Blanchet.

The outcome? Truly mobile healthcare.

Urban dwelling

The dwellings refugees and migrants now find themselves in are another change to the tradition. More of them are veering away from stereotypical refugee camps and choosing cities to house them during their transition. “There’s this increasing growth of urban refugees and IDPs,” says Dr Roberts For some, urban living can provide greater opportunity.

However, with urban dwelling comes the challenge of finding people and providing adequate healthcare services for those in need. “Compared to well-established refugee camps, in cities it can be harder to identify where people are, provide services and conduct public health activities,” admits Dr Roberts.

An advantage of well-established refugee camps, typically run by the UN, is that they can ensure housing is far enough apart to reduce disease spread. They also work to make sure that water and sanitation facilities are good enough to prevent the spread of infections and provide humane living conditions. The ability to do this in practice, however, can be limited.

Refugee camps are more able to ensure access to health services for large populations, including referral services, vaccination drives and surveillance systems to record births, deaths and disease outbreaks. This is the case in well-known camps such as those in Dadaab, Kenya, which has been run by the UN for many years.

“The problem is that they’re not temporary,” says Dr Roberts. Some lives, and childhoods, have been based in refugee camps, with the average refugee now residing in camps for 17 years.

But around such permanence, can come the very opposite — transience. There is potential for informal camps to be set up elsewhere, resulting in high mortality from outbreaks.

“People go to places they know are safe and camps form around them,” says Dr Jennifer Palmer, Research Fellow and medical anthropologist at the School. This has taken place around UN structures in Bangladesh as well as camps in Uganda and Congo. “They’re here this year and won’t be next year,” she says.

Planning for a family – in a camp

Dr Palmer has been researching family planning services in settings of crisis and displacement, including camps in Juba, South Sudan. Here, despite largely experiencing better access to health care, women also face unexpected social circumstances that come with living in such a managed setting.

“There is always a need to integrate family planning into emergency response programmes,” says Dr Palmer who sees emergencies as an opportunity to improve health services in countries where they were previously inadequate. However, when culturally- and politically-controversial reproductive health services such as family planning are new to a population, there is inevitably a period where new social norms need to be negotiated.

“Women move to Juba for a more liberal life and now find themselves in camps where they can’t use contraception,” says Dr Palmer. South Sudan has the highest fertility rate in the world, with more than 5 children born per woman, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) whose figures also reveal a continued high risk of maternal death, affecting 1 in 26 women.

"They have to keep moving because as long as a border is open, it’s their only chance…It’s very hard to save lives while people are walking."

Dr Karl Blanchet, Co-founder of Public Health and Humanitarian Crisis Group at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine

As women find themselves living in extremely close proximity, and under the eyes, of those around them, negotiations become more public and their personal preferences can go unheard — socially and culturally. A woman’s body is under much closer surveillance. “Women move to Juba for a more liberal life and now find themselves in camps where they can’t use contraception,” says Dr Palmer.

As the needs and circumstances of people change, so do the health and research priorities associated with them. The people moving are not the same as they were decades ago. The health issues affecting today’s migrants and refugees are different, and more complex, than they were just years ago. The fight is no longer simply against communicable disease but instead a plethora of diseases and health conditions — all determined solely by the population in flight.

One thing remains the same: the need to stay healthy physically and mentally. Health continues as a key possession for people to take with them, and maintain, on the road, regardless of where they came from.

“We’ve experienced numerous crises….but when we see these refugees being welcomed today a sense of humanity is restored, seeing them as human beings who need care and support,” says Dr Blanchet.

Prof McKee agrees. “We need to move away from the rhetoric of swarms of migrants and point out that we need these people.”

Cover images and video courtesy of UNHCR